- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijns

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Marja Elsinga

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Marietta Haffner

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Henk Jonkers

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Chiara Tobia

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Afua Wilcox

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

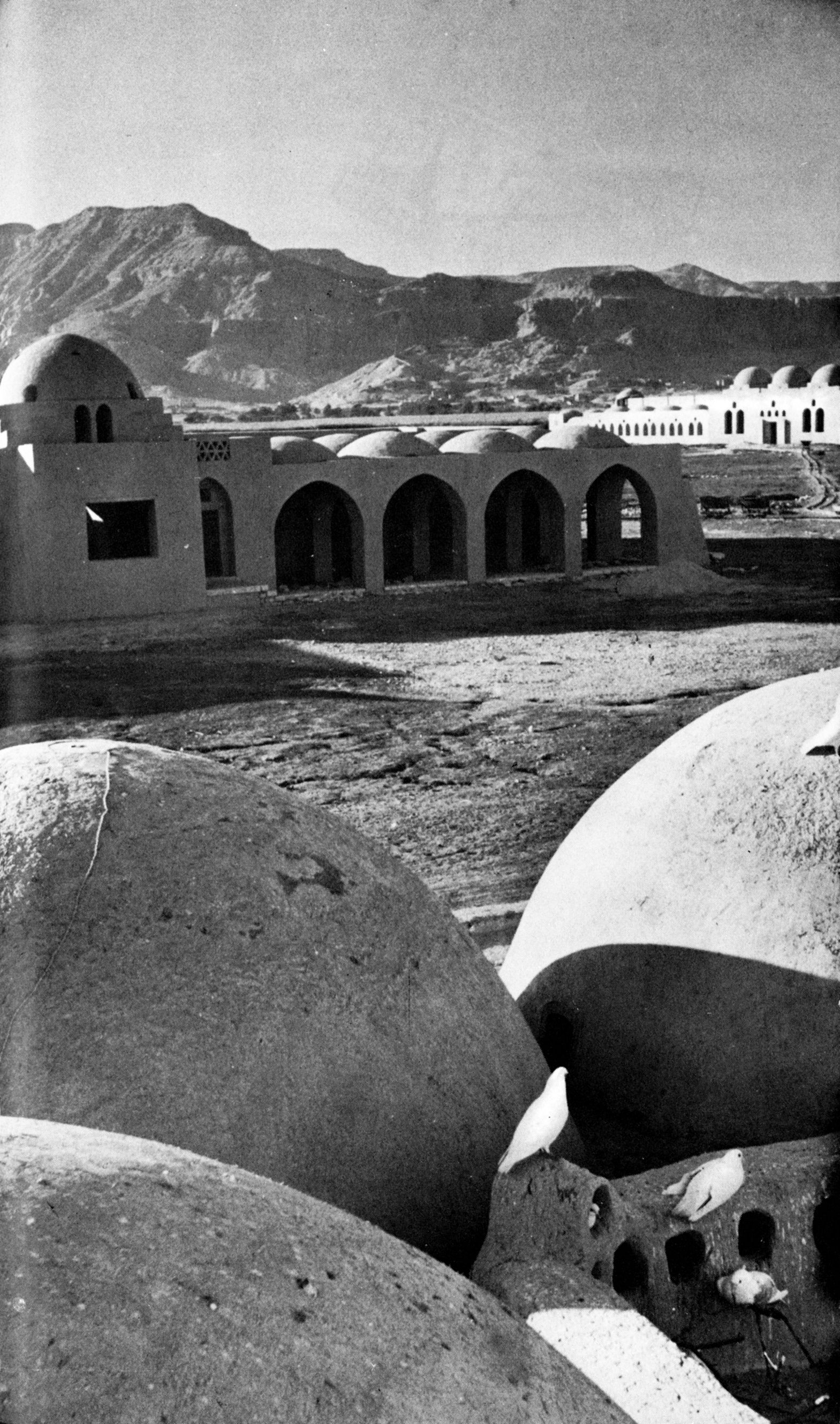

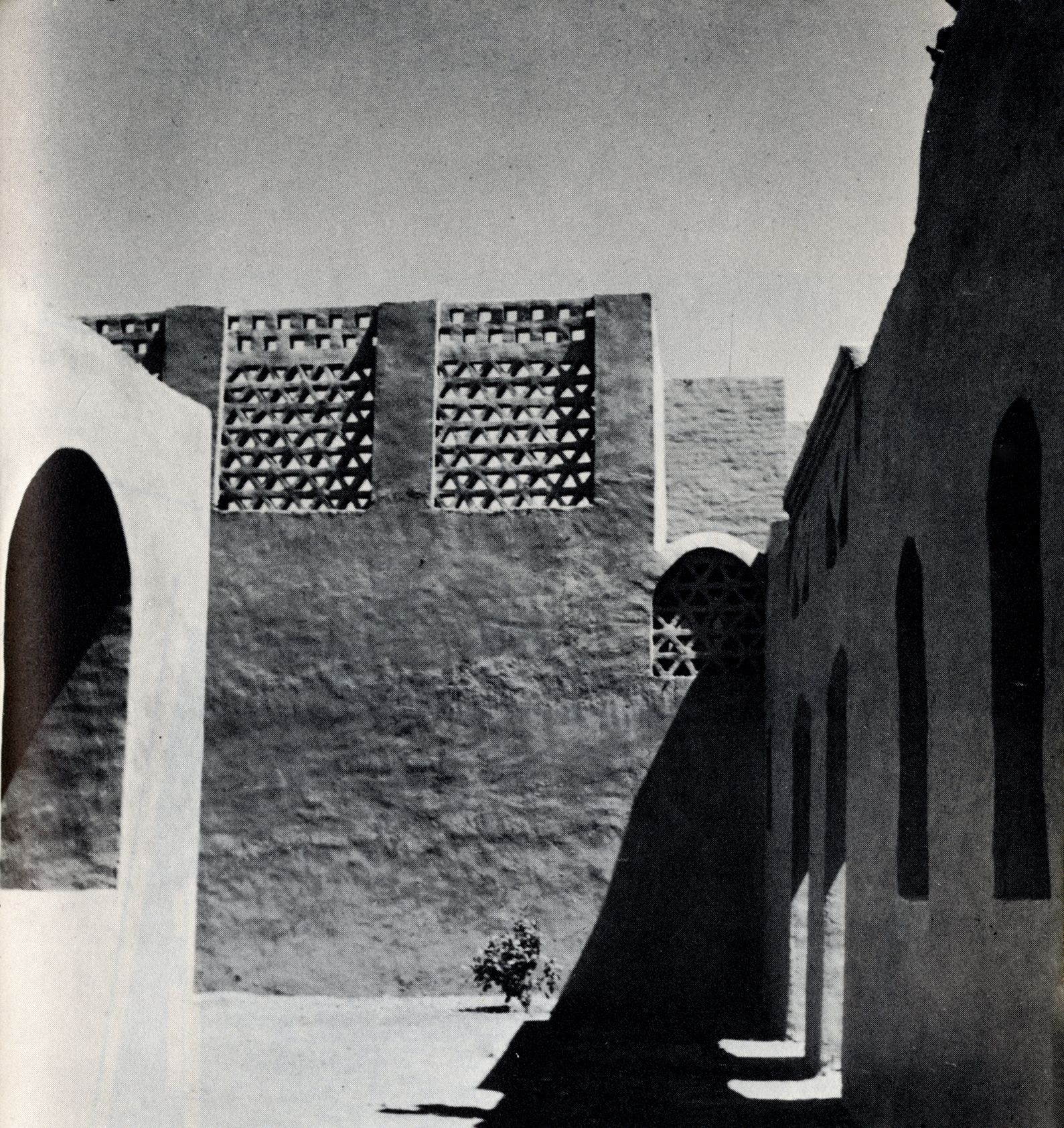

New Gourna Village

Hassan Fathy

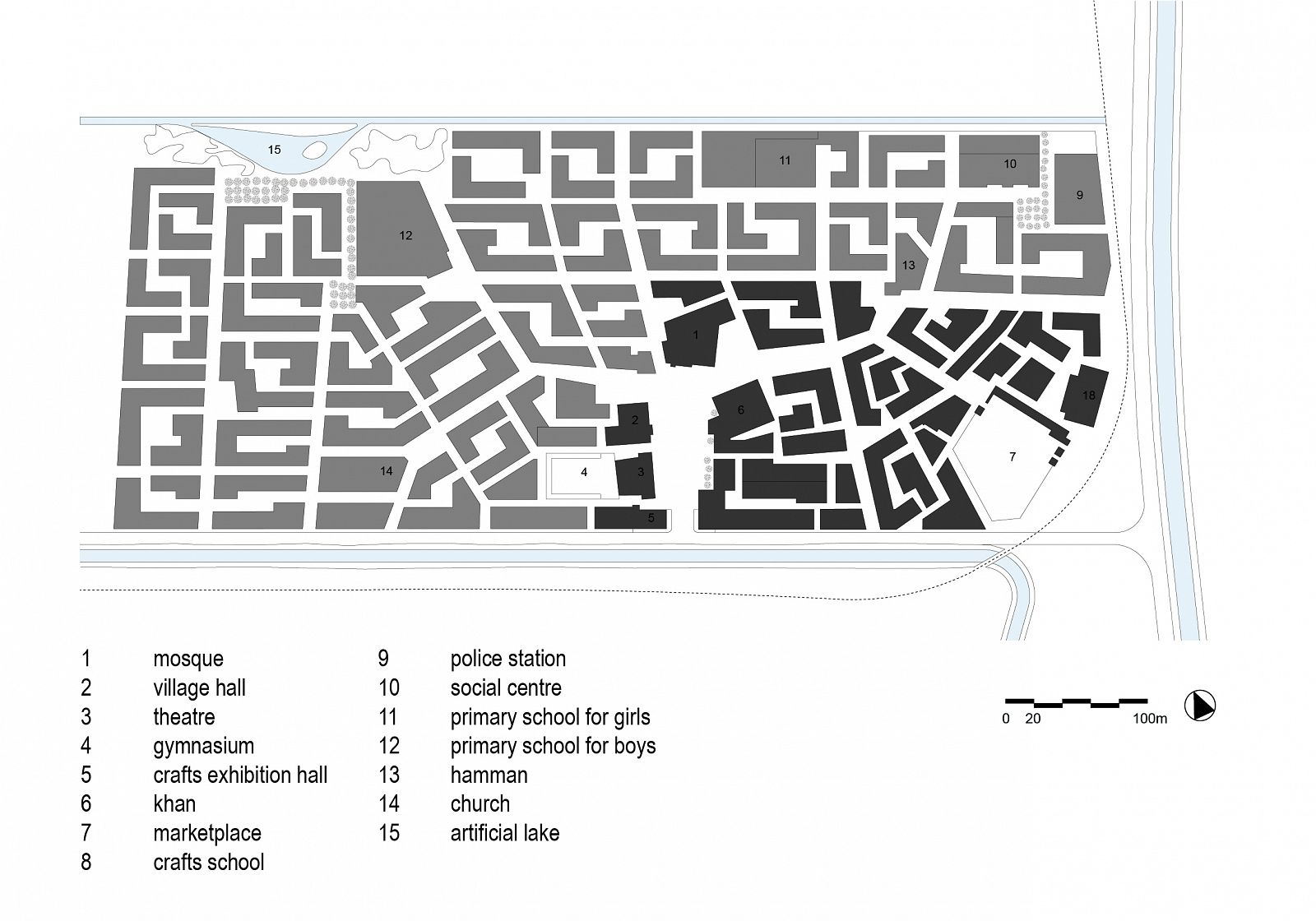

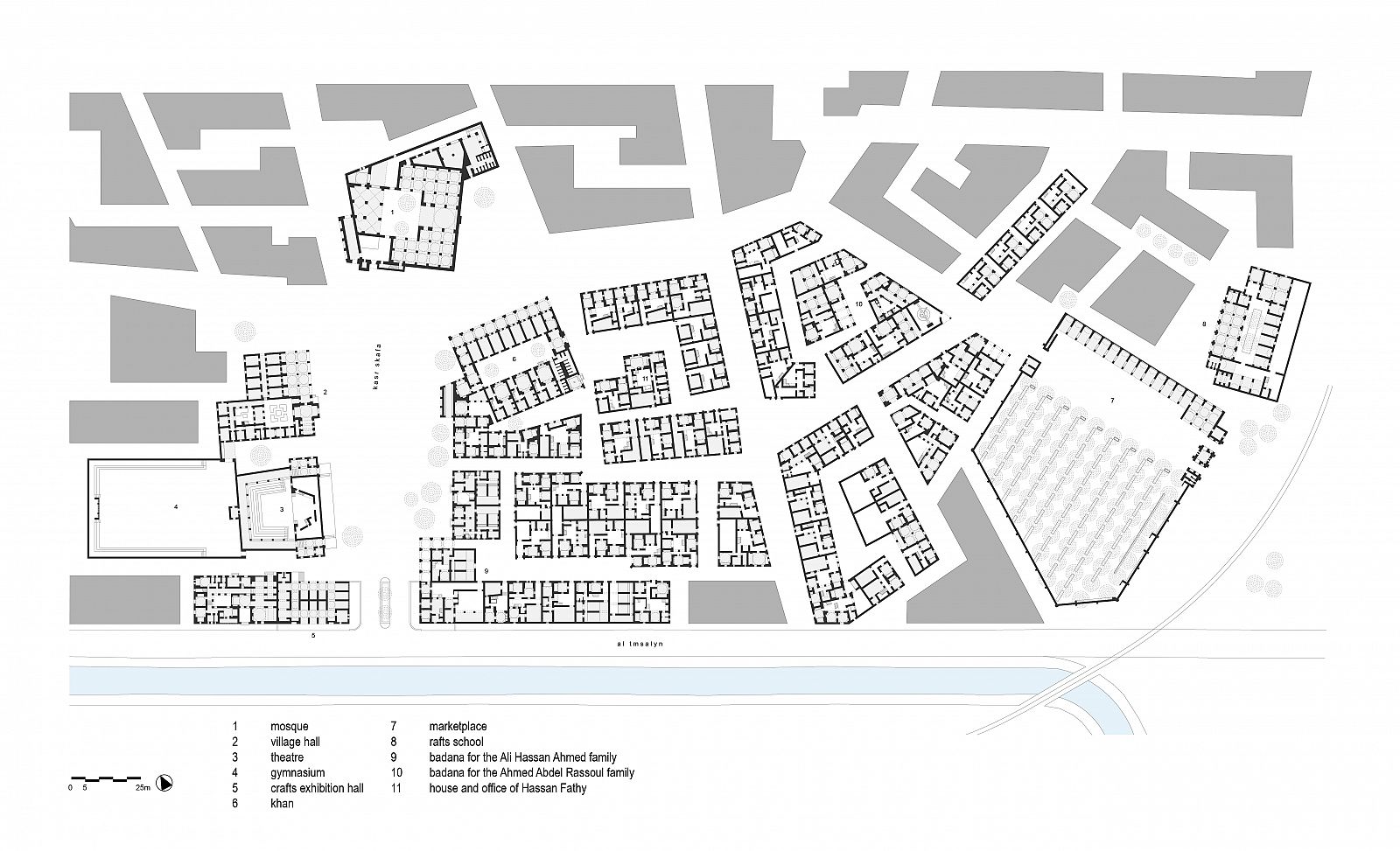

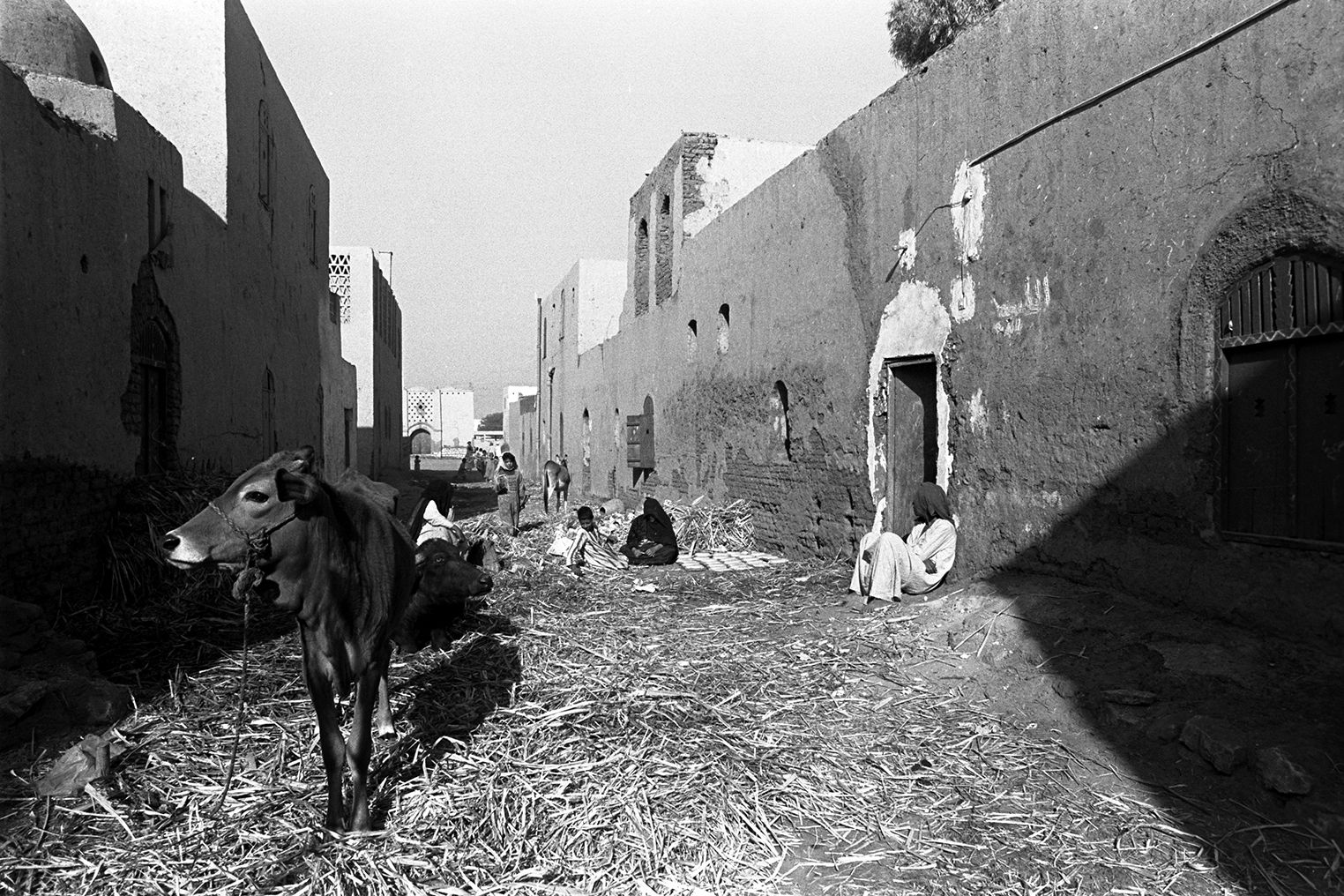

In the nineteenth century, Gourna was a small farming settlement at the foot of the Theban necropolis, near present-day Luxor. By 1945, it had evolved into a village of approximately 7,000 inhabitants that subsisted mainly on ransacking the many tombs dating back to the days of the ancient Egyptians. The Egyptian Department of Antiquities, in an effort to solve this problem, decided to move the village to a location closer to Luxor. Hassan Fathy was commissioned to design and build a completely new village for the resettlement of the Gournii.

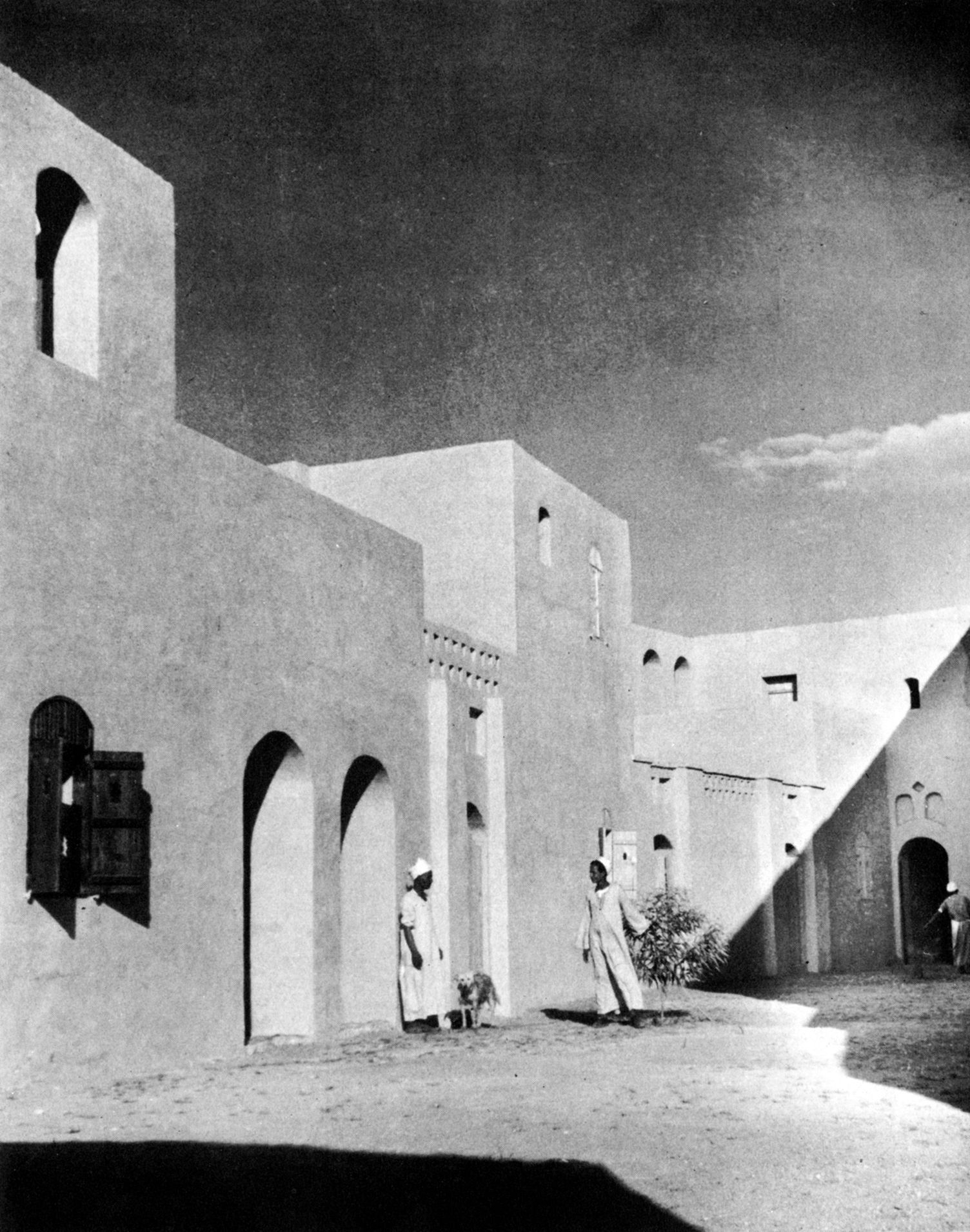

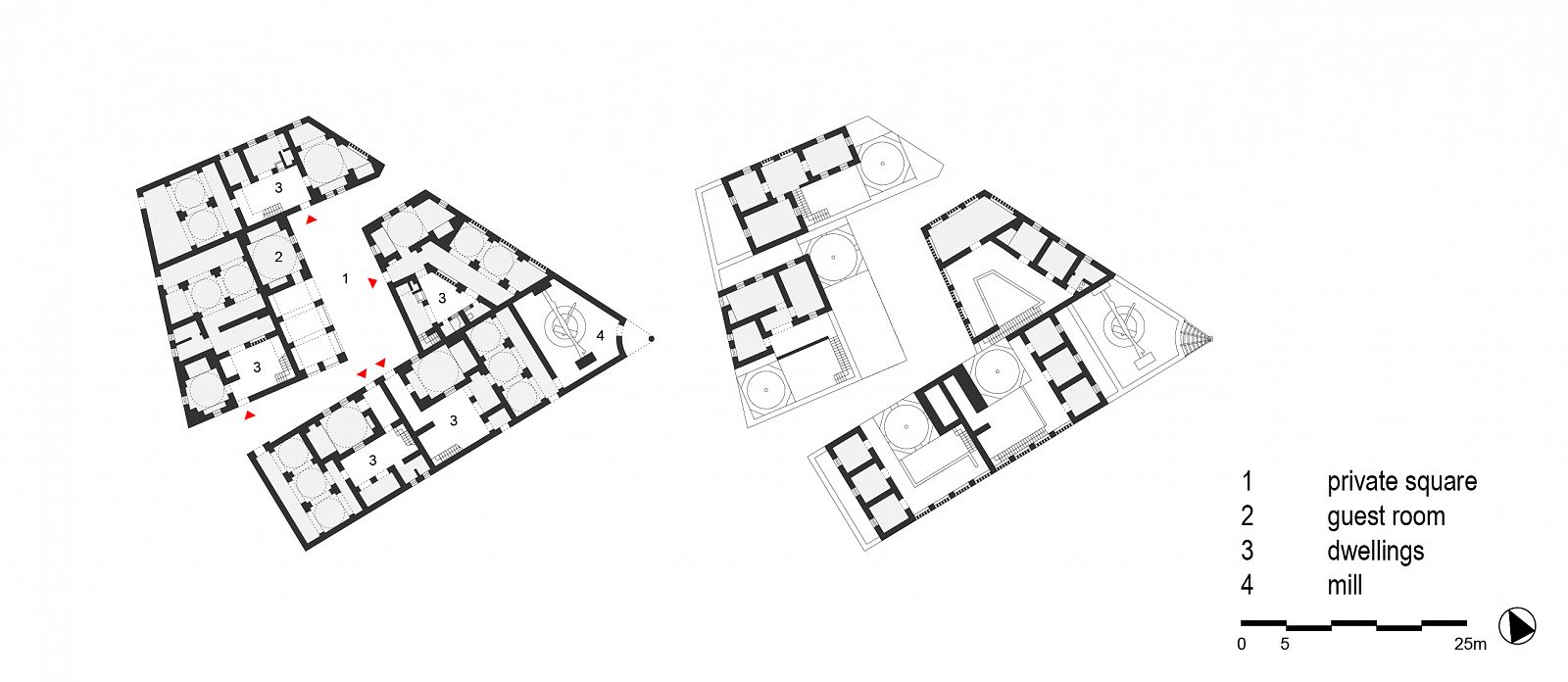

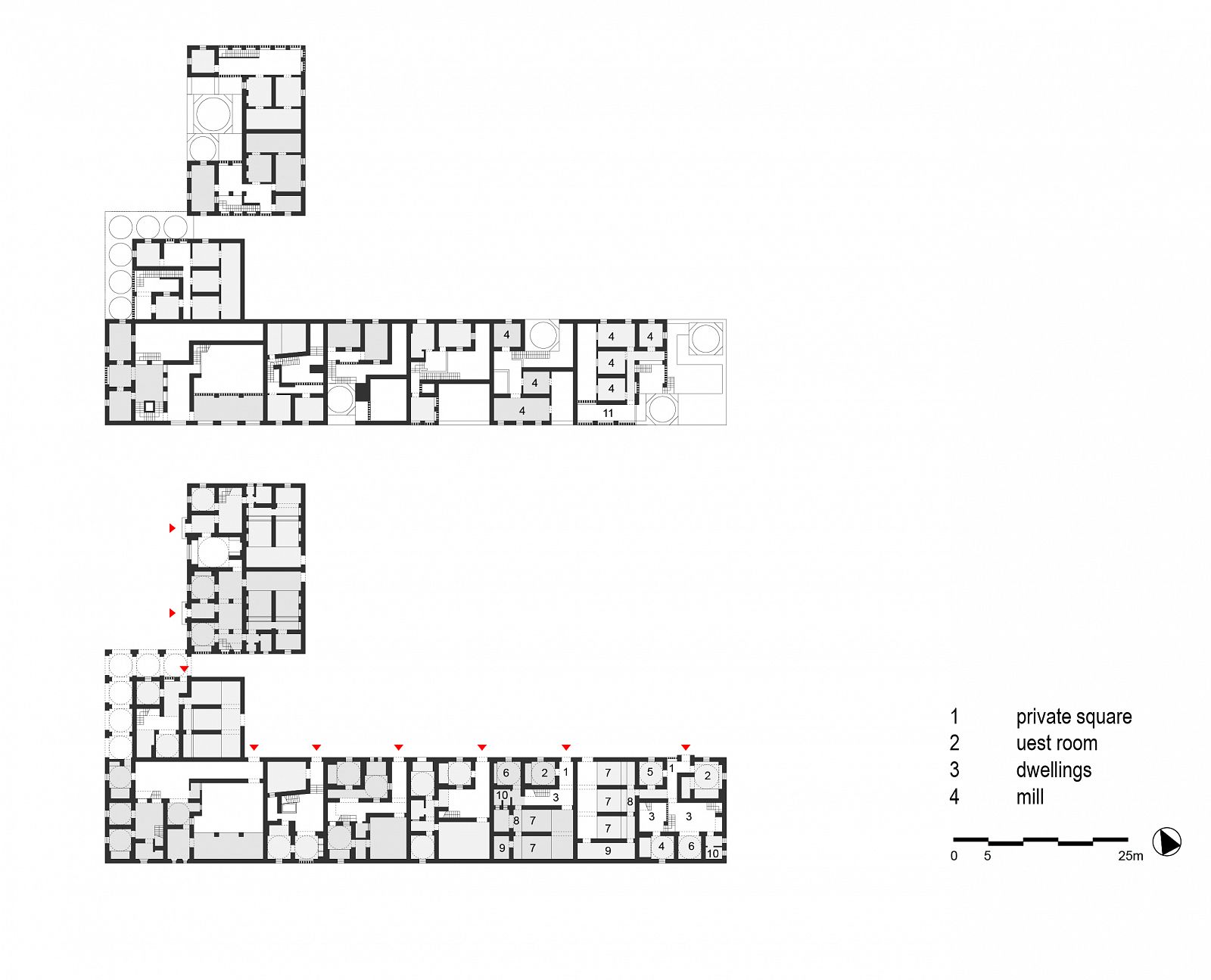

Fathy felt that New Gourna could only become a success if his design took local custom into account and integrated the architectural typologies of the old village. Fathy therefore based his urban design on the badana. A badana is a community of people that consists of some ten to 20 related families – headed by a sheikh – and functions as a single socioeconomic unit. In the completed part of New Gourna, four districts can be distinguished that each accommodate one or two badanas. Open spaces are arranged hierarchically in each cluster. Fathy favoured gradual transitions between a dwelling’s interior and the outdoors and vice versa. The dwellings are therefore designed around small courtyards. In Arab culture, the courtyard is more than just an architectural resource to create privacy and protection: it serves as an outdoor room, with the four walls supporting the dome of heaven. In addition, it constitutes the first transition from the interior to the outdoors; from private to (more) public. The dwellings are clustered to enclose a small, semi-public space, which eventually joins onto a public street or square.

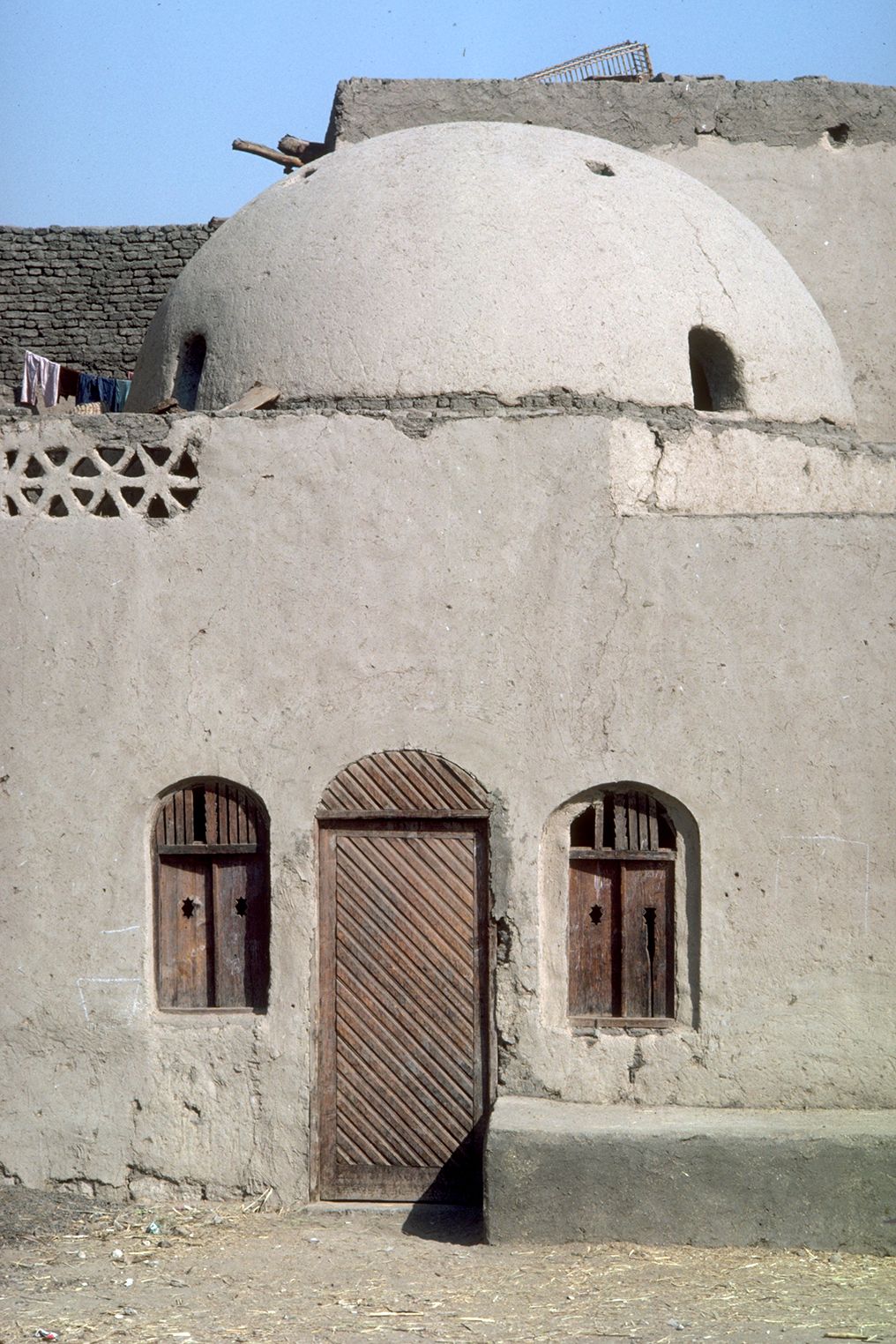

All buildings in New Gourna are built entirely of mud bricks – a cheap and locally available material. The pit dug to acquire the mud was integrated into the urban plan to serve as a lake. When building with mud bricks, it is best to choose domes and arches as construction elements: the rectangular rooms inside the dwellings, including the bedrooms, therefore have domed roofs. Each of the beds is in an alcove (iwan) fit with a special gutter that offers protection from scorpions. Many dwellings include an indoor space for livestock on the ground floor. The plan included the realization of both dwellings and countless amenities including a Kahn (an inn and trading place for caravans), a mosque, a primary school for boys and a separate school for girls.

Despite sincere attempts to design New Gourna in a socially responsible manner, the Gournii refused to move into their new village. To Fathy’s great disappointment, only onefifth of the village was ever completed and years later, in 1961, only part of the village was inhabited. Over the years, many new dwellings were added and Fathy’s houses fell into disrepair. Mud-brick structures require a lot of maintenance, which the residents simply could not afford. The groundwater level also rose, causing the salt from the sandstone foundation to dissolve and the dwellings to subsequently collapse. Alarmed by its worrisome condition, UNESCO initiated a project for the preservation and reconstruction of the village in 2009. Unfortunately, the project was temporarily discontinued in 2011 due to the Egyptian Revolution.

Many decades after the first attempt to resettle the population of the old Gourna, the government repeated the initiative on the basis of identical arguments (protecting tombs from being ransacked). This time, the new location is farther away from the old Gourna, in a suburb of Al Taref. The construction of the new development began in 1997 and the massive relocation of, by then, more than 20,000 Gournii began in 2006. And this time, to force the population to abandon their homes, old Gourna was levelled. The starting points for the design of the second New Gourna were nowhere near as social as Fathy’s: the rigidly planned neighbourhood provides every family with an identical standard two-bedroom dwelling.

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Source: Hassan Fathy, Architecture for the poor (Chicago University Press, 1973), ill. no. 69

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Source: Hassan Fathy, Architecture for the poor (Chicago University Press, 1973), ill. no. 73

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Christopher Little

Source: Hassan Fathy, Architecture for the poor (Chicago University Press, 1973), ill. no. 55

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Christopher Little

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Christopher Little

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Matjaz Kacicnik

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Matjaz Kacicnik