- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijns

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Marja Elsinga

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Marietta Haffner

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Henk Jonkers

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Self-built

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Chiara Tobia

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Afua Wilcox

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

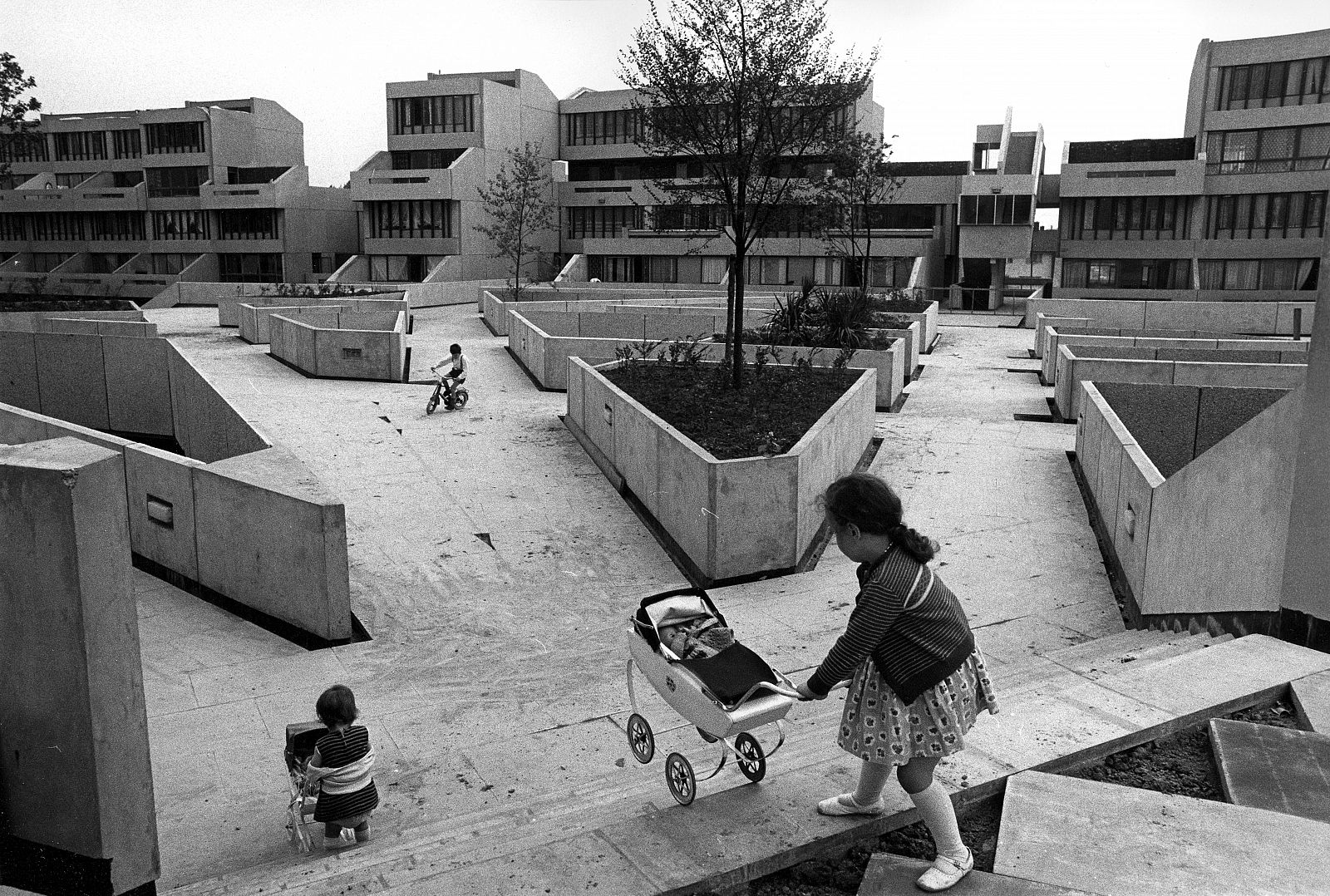

Thamesmead

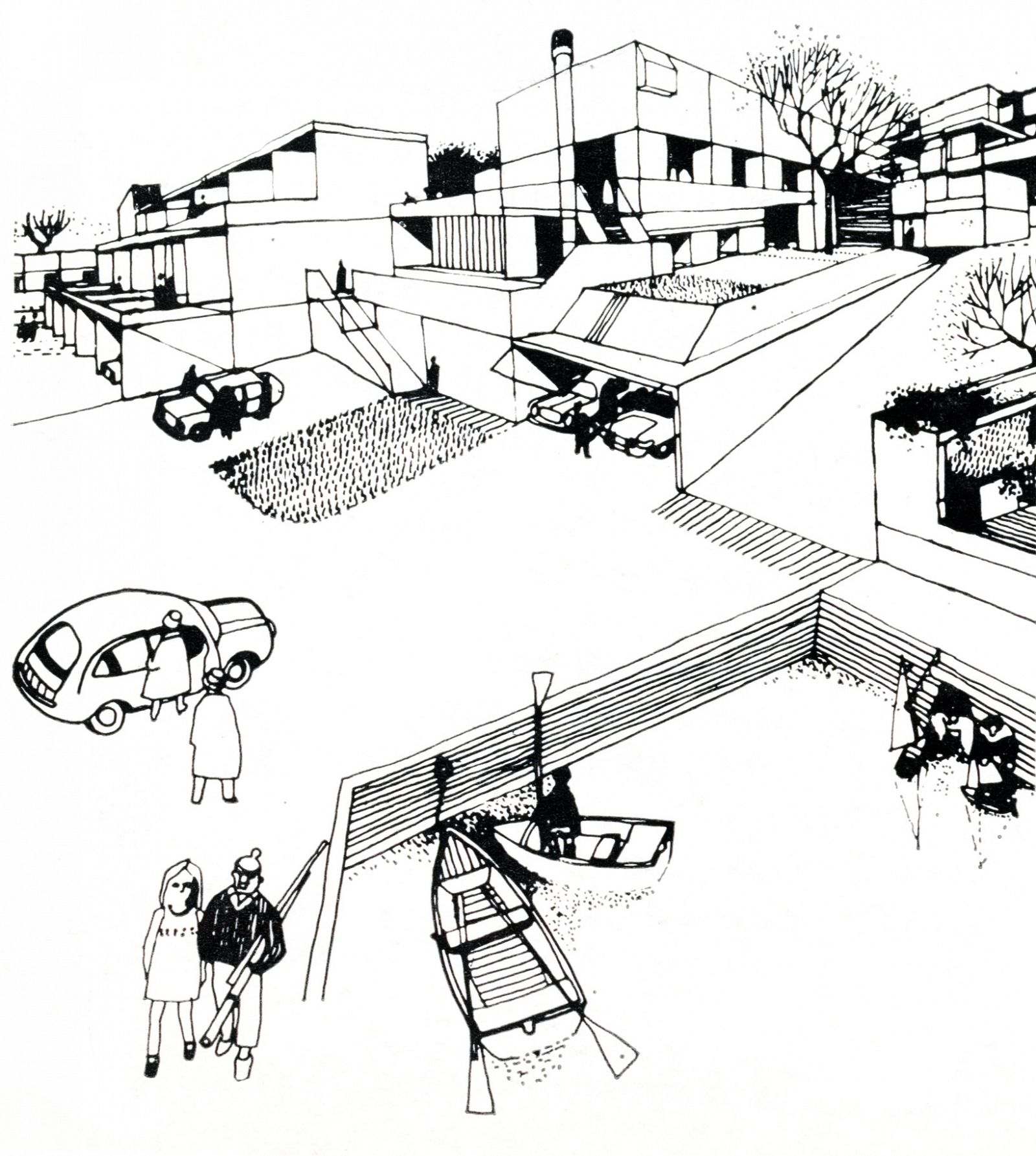

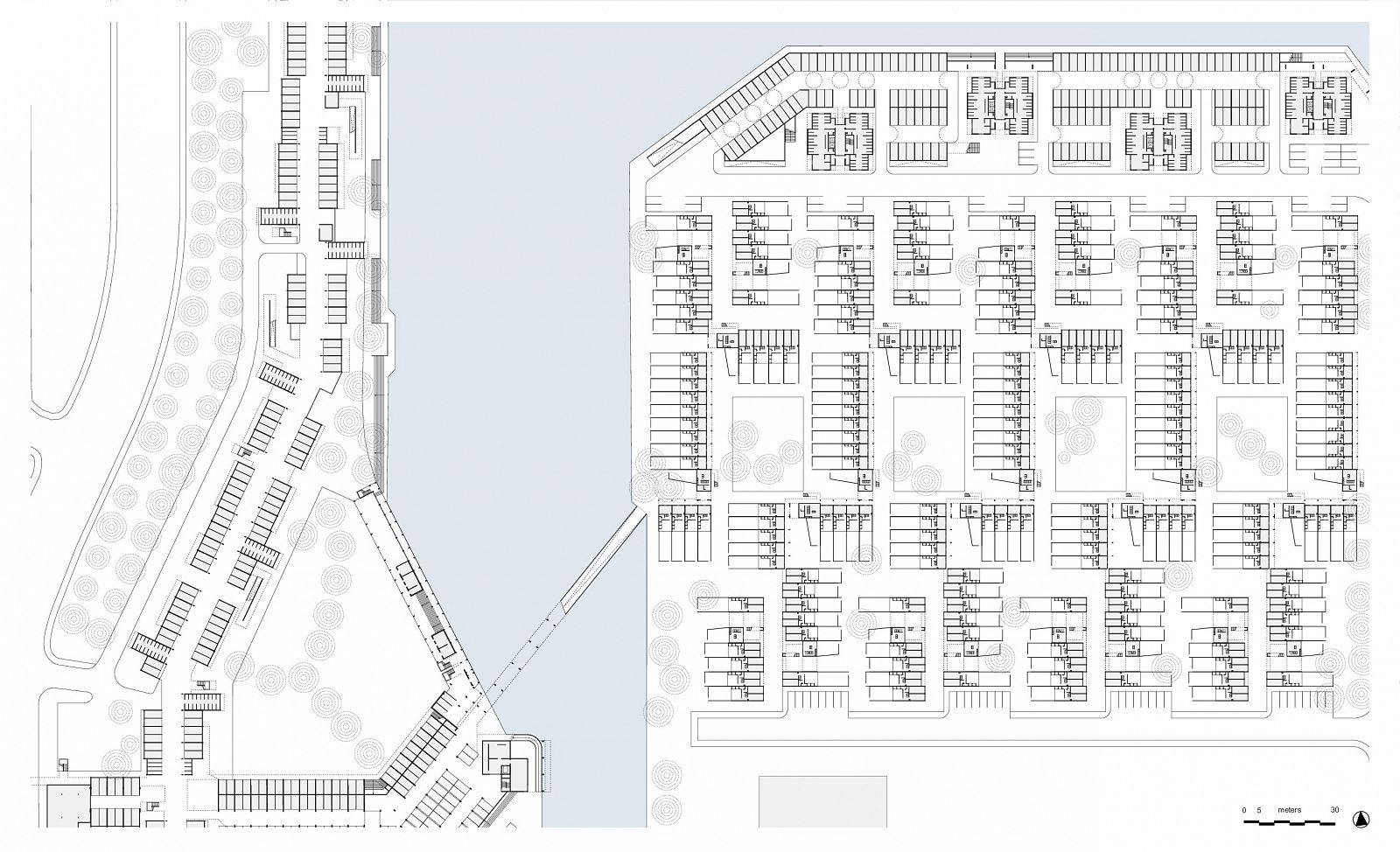

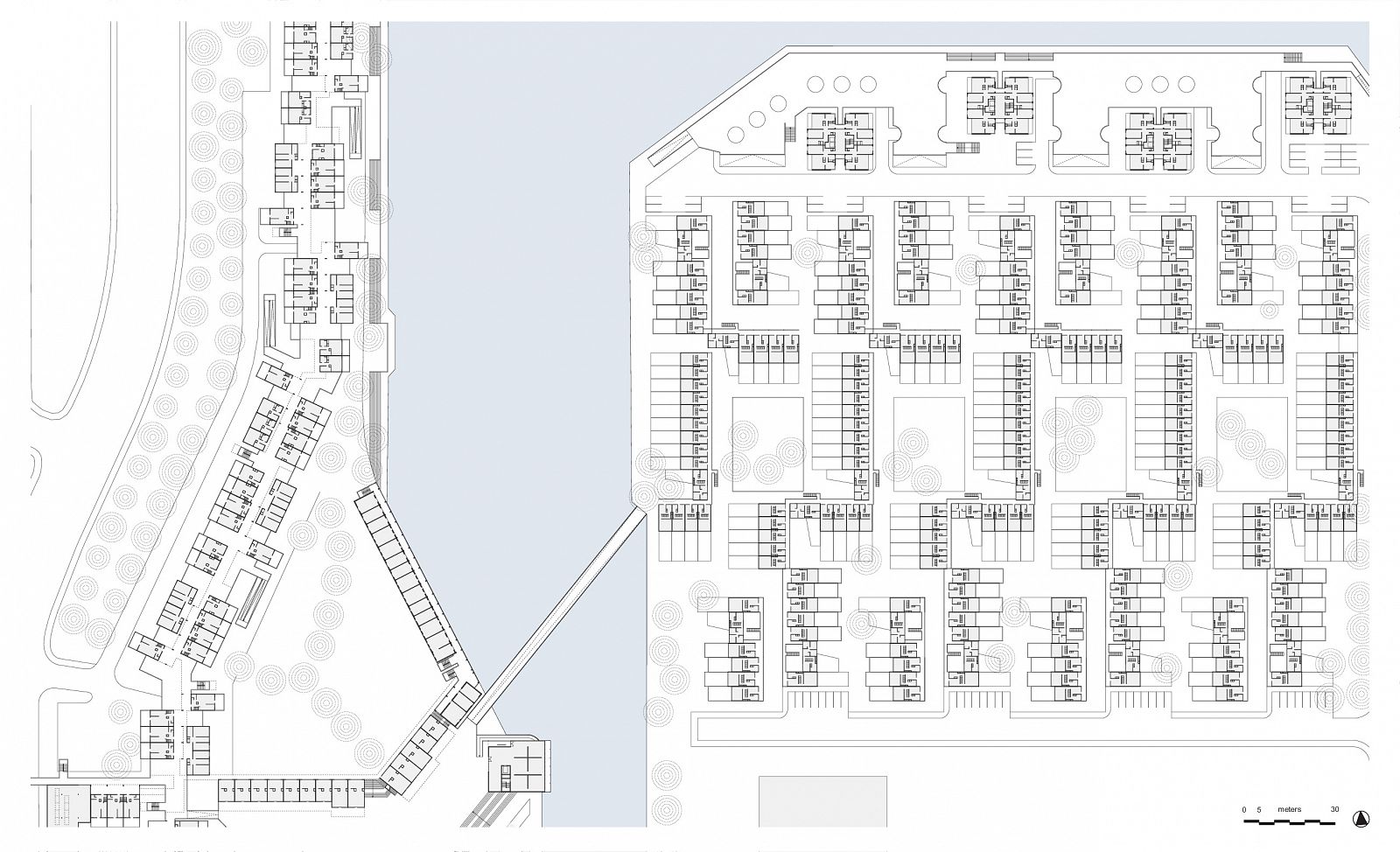

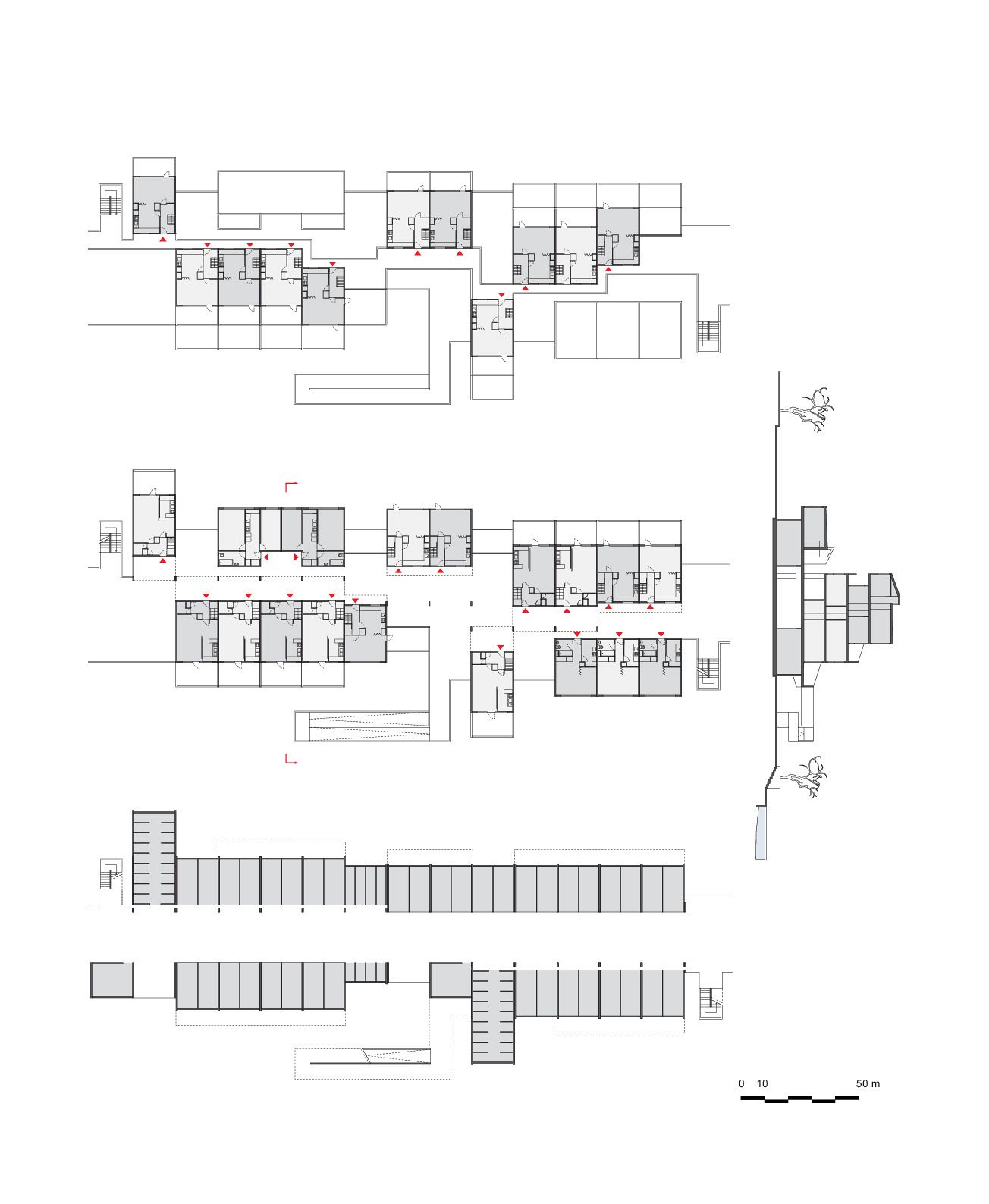

In the mid-1960s, the Greater London Council (GLC) initiated the setup of a programme and design of a New Town for no less than 60,000 people in East London: Thamesmead. After the First World War, the GLC had begun the large-scale demolition of inner-city slums consisting of Victorian back-to-back dwellings built for the working classes. This slum clearance process continued through the 1950s, 1960s and 1970s. Thamesmead was intended, among other things, for the resettlement of families from the cleared neighbourhoods. The location of the new residential area was to be the site of the Woolwich Royal Arsenal, which had fallen into disuse. This originally low-lying wetland area between the River Thames and the Abbey Wood hills had been deemed unfit for large-scale development for years due to poor soil conditions and the danger of flooding. However, lack of space and a high-pressured housing market changed all that and the location was developed despite the risks. Unlike the first generation of English New Towns, which was considered monotonous even then, Thamesmead was to become an example of the ideal New Town, with a wider variety of building typologies as well as more space for employment and services. The original 1967 master plan shows a large number of long-meandering blocks, the so-called spine blocks that form the back bone of the district: a long string of buildings along the Thames with branches going inland converging in a large central area around a marina by the river. The spine blocks created a wind and noise buffer for the low-rise neighbourhoods lying behind them, while offering a safe traffic route from the residential areas to the centre through an internal system of raised pedestrian roads. In accordance with the then prevailing opinion that the separation of traffic types through a raised pedestrian circuit would result in a safer living environment (which was also applied, for instance, in the London Barbican, see DASH – The Urban Enclave), an internal system of routes through the spine blocks was developed. In the case of Thamesmead this was in perfect keeping with the requirement that because of the danger of flooding, there were to be no residential spaces on the ground floor and escape routes had to be present at every level. The other restrictions of the location are also used to beautify the neighbourhood and make it more liveable. An intricate system of water courses was proposed for the purpose of water storage; the boggiest areas were transformed into small lakes. In advance of the construction on location, building firm Cubitts put a factory in place for the production of prefab elements to allow the quick building of a large number of houses. Only the first phase of this ambitious master plan, Thamesmead South, was realized. In accordance with the master plan, the spine blocks are situated along the north south through route in the direction of the planned centre on the Thames. The complex composition, with a lot of height differences and staggered façades and balconies, provides the blocks with a varied and expressive exterior. Located on top of the parking garage is a raised pedestrian deck flanked alternately by stacked maisonettes and one-storey dwellings for seniors. Bridges also connect the deck to the community centre by the lake and to parts of the two raised neighbourhoods behind it. Here, in a repetitive pattern of staggered short blocks, single-family dwellings are clustered around parking courts or, alternatively, green, car-free courtyards. To achieve the required housing density, a number of identical residential towers housing single or double households are situated along the fringes, some along the south shore of the lake and some along the east-west access road. In the early 1970s, high construction costs and new insights led to drastic changes in the master plan: the shopping mall, the marina and the new cross-river connection were dropped. The Cubitts factory was closed and later residential areas built in accordance with more organic home-zone principles. Thamesmead South has been struggling with a negative image for many years. As it turned out, the design ideals worked out badly in practice. The raised ground level, for instance, led to a deserted ground floor with a lot of unsafe or inaccessible areas. Only a few years after the completion of the project, the recording there of some illustrious scenes for the Stanley Kubrick film A Clockwork Orange confirmed that image. Today, many of the prefabricated concrete dwellings are highly outdated technically and some of them have passed into private hands through the ‘right to buy’ system. Overdue maintenance and the many individual additions make the neighbourhood look cluttered and neglected. The current owner of the rental housing, the Peabody Trust housing association, recently announced a major restructuring of the area. In anticipation of this, part of the original community centre by the lake has already been demolished.

Drawing: © Delft Architectural Studies on Housing

Drawing: © Delft Architectural Studies on Housing

Photo: Tony Ray-Jones, © Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections

Photo: Tony Ray-Jones, © Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections

Photo: Tony Ray-Jones, © Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections

Photo: Tony Ray-Jones, © Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections

Photo: Tim Street-Porter, © Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections

Photo: Tony Ray-Jones, © Architectural Press Archive / RIBA Collections