- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijns

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Marja Elsinga

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Marietta Haffner

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Henk Jonkers

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Chiara Tobia

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Afua Wilcox

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

Mickey Leland

Housing Development Project Office (HDPO)

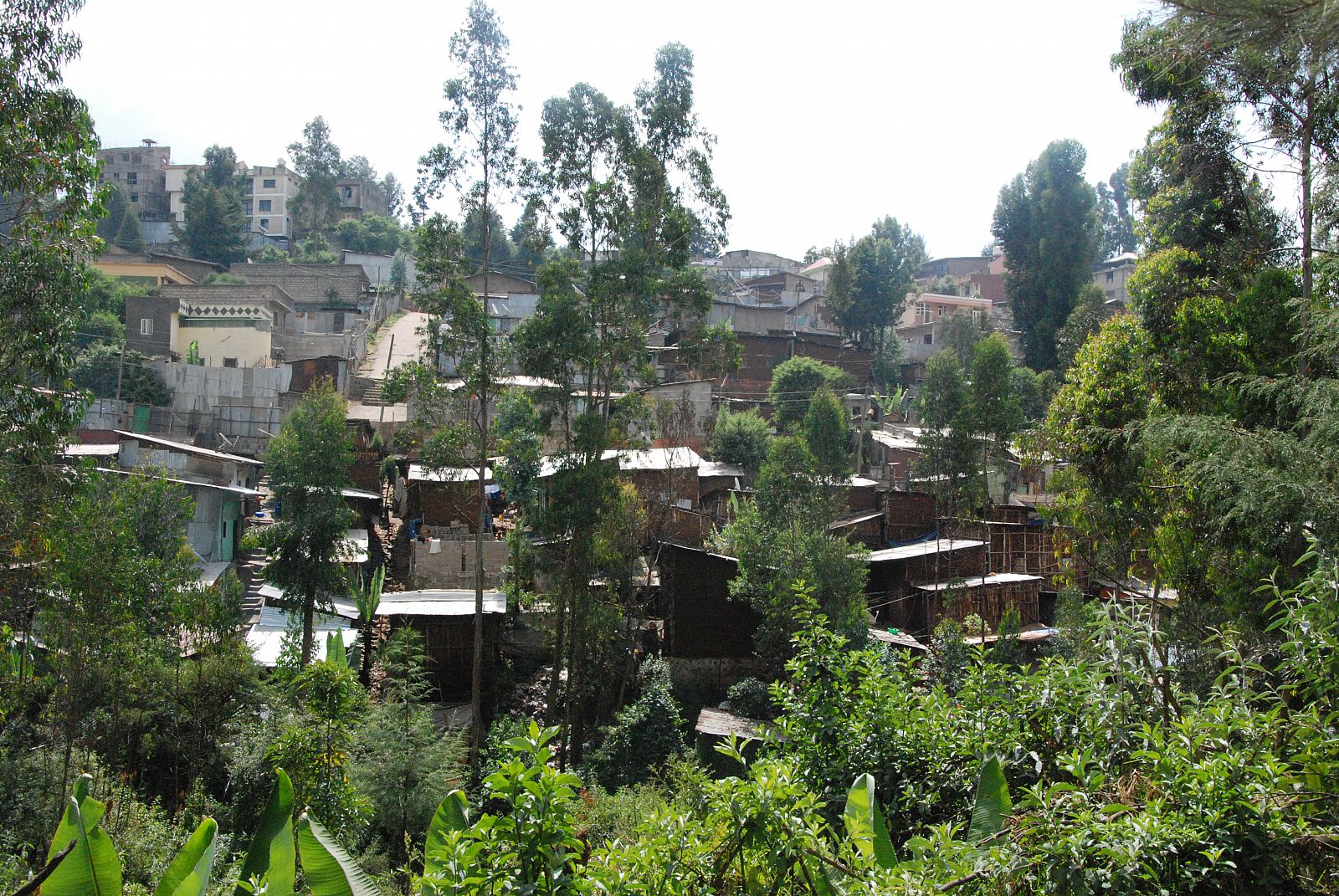

Addis Ababa, the capital city of Ethiopia, is one of the 35 fastest-growing cities in the world. According to predictions by UN-Habitat (2015), in this decade the population of Addis will grow from 4.1 to 4.9 million. Even though it is always debatable how slums are defined in Addis Ababa, UN-habitat estimates that 76.4 per cent of the total urban population lives in slums or under substandard conditions. In 2004, the Ethiopian government started the so called ‘Grand Housing Program’ to eradicate the slums and to care for the urban poor. Cross-cutting agendas here were: 1) to create 200,000 jobs; 2) to promote the development of 10,000 small scale enterprises; 3) to deliver 6,000 ha of serviced land; and 4) to enhance and build the capacity of local contractors, consultants, etcetera. Initial pilot projects were tested in the city of Addis Ababa and later the programme was scaled-up to a nationwide housing initiative. So far, in Addis Ababa alone, 240,000 housing units have been built. Mainly built as condominiums, the dwellings are infills of small vacant lots in the existing city fabric, or are a replacement for slum-cleared areas. But a large number of these condo sites are located on the fringes of the city, like the Mickey Leland Condominium Site.

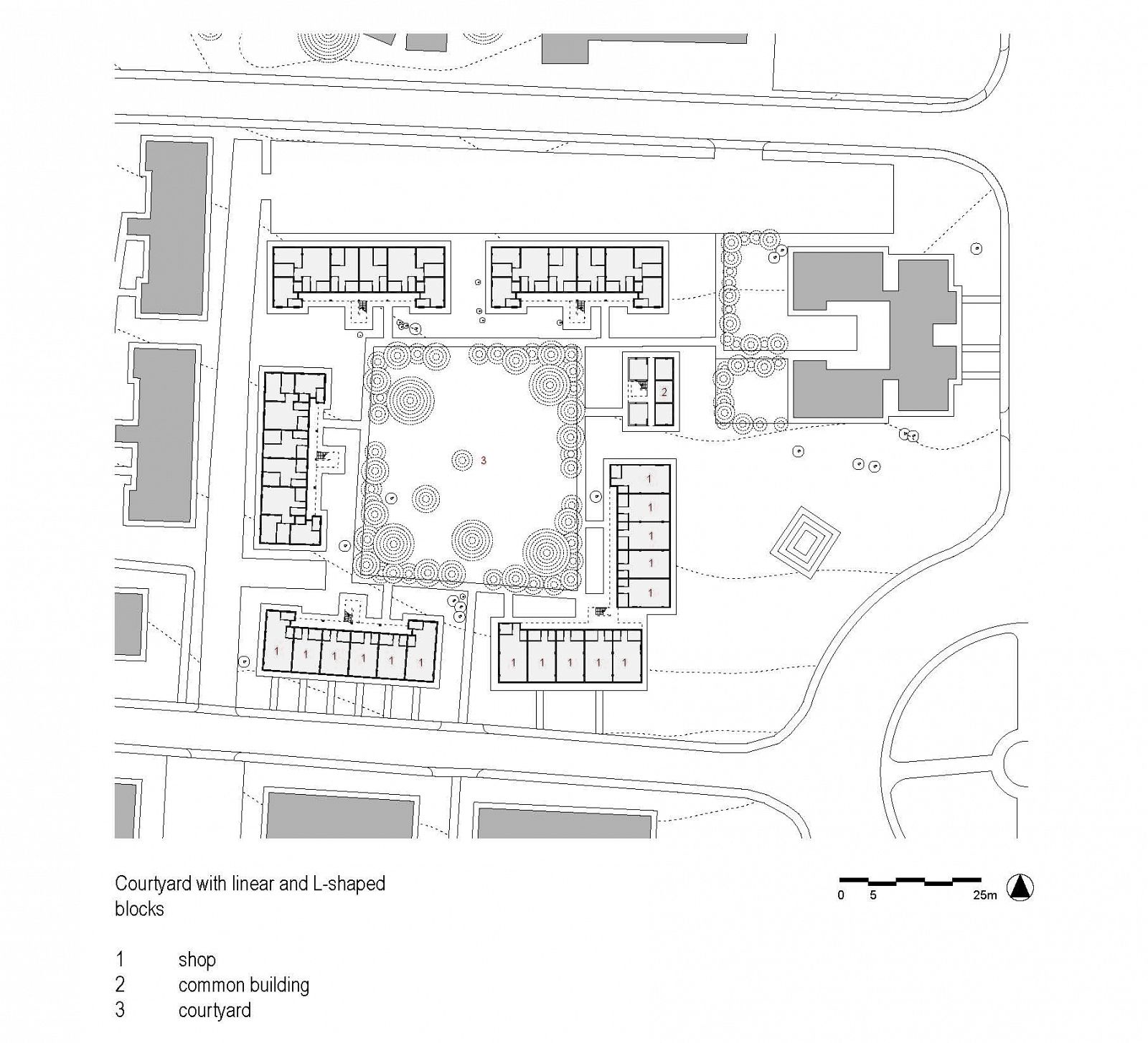

Mickey Leland is located in the north-western part of Addis Ababa, situated on a 26-ha-steep site sloping southwards. Named after George Thomas Mickey Leland – an anti- poverty activist and congressman from Texas, who died in Addis Ababa in 1989 – the housing project consists of 123 blocks with five different typologies. Every typology has slight variations, in some cases, for instance, the ground floor is filled with commercial use and in others is used for housing, depending on the location of the block within the neighbourhood. An estimated 24,000 dwellers live in the 4,800 housing units.

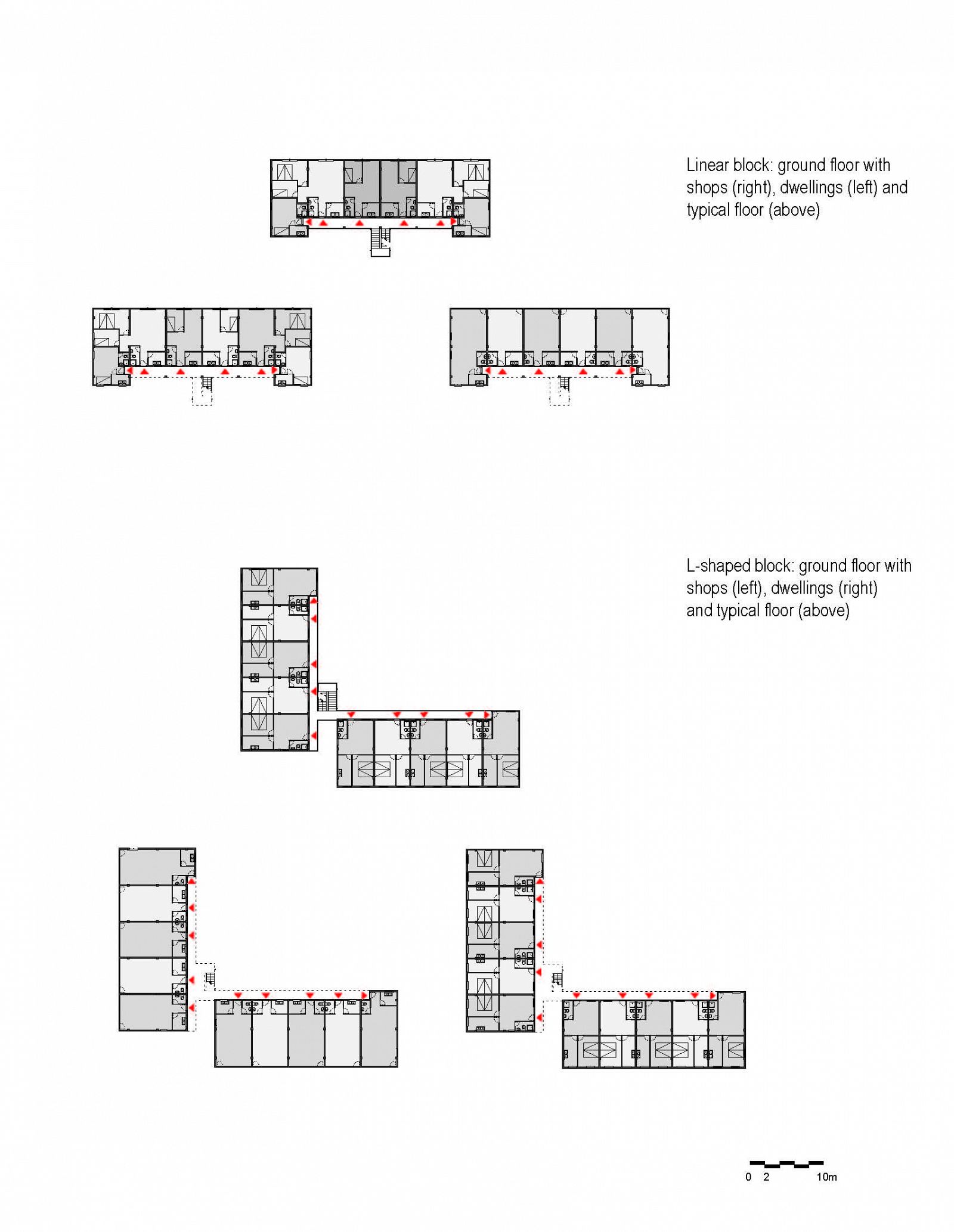

The most recurrent block typology is the so-called C5 Type, constructed with a frame of reinforced concrete (precast beams) and hollow concrete-block masonry infill. It always consists of five storeys, the maximum height for which no elevator is required. An exterior steel stairwell, placed in the middle of the façade, connects all floors and gives access to galleries, which in turn connect all units on a floor. The C5 Type consists of 40 units: ten studio units, ten one-bedroom units and 20 two-bedroom units.

Like many social housing schemes, Mickey Leland faces the clash of architecture, program and typology with culture and lifestyle. For example, the most common way of food preparation in Ethiopia requires a cooking space in an outdoor yard. This programmatic need was translated in most condominium housing by providing a shared ‘cooking building’, but most of these cooking-buildings are not used as envisaged because of their inconvenient placement, too far away from the individual dwelling. Instead, inhabitants choose to extend their kitchen space onto the gallery, where it is further appropriated and privatized, especially for the units at the two corners of the floor. Similar examples of spatial appropriation occur on the balconies where residents extend their living spaces with simple structures. Mickey Leland is not short of open space, but it has not been designed or adjusted to meet important programmatic needs, for example parking. Since the condominiums were never envisaged for higher-income groups, the issue of parking was not addressed. Upon completion, it became obvious that the lack of parking space is problematic. Many open spaces are therefore being converted into parking lots or for example satellite-dish yards.

Although better fitted with infrastructure and services than regular slum areas, one cannot but notice Mickey Leland’s barrenness and monotonous architecture. This is, however, mitigated by the topography, which has resulted in a cascade of buildings. The monotony of form and morphological flatness is counterbalanced by inner courtyards and retaining walls that give a strong definition of space.

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Photo: © Brook Teklehaimanot

Photo: © Faisal Girma