- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijn

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

Mediating Informality

The Urban Visions of Peru’s Law 13517

In 1949, Lima’s modernist apotheosis appeared imminent: the Plan Piloto, the city’s first master plan, had applied the techniques of scientific planning to analyse the city at its various scales – from the historical core to the agricultural areas supplying it with food – and to establish a logical course for ‘channelling its urban development’.1 But by 1954, a follow-up study warned that ‘the overflowing vitality of the metropolis in its blind force of expansion’ was setting in train problems which would only intensify over time: ‘the traffic congestion endlessly increases . . . delinquency grows; the city is choking itself in a dreadful ring of clandestine dwellings . . . a drop in the standard of living threatens.’ All this was the result of an unprecedented rate of population growth, largely due to rural-urban migration: established planning processes were being overtaken by the rapid emergence of barriadas (squatter settlements), as authorized housing could not be built quickly and cheaply enough to meet the demand. Reluctantly, the study confessed: ‘An economical system of urbanization and construction that would allow us to avoid the overcrowded and unsanitary conditions that appear in the “clandestine neighbourhoods” has not yet been devised.’2

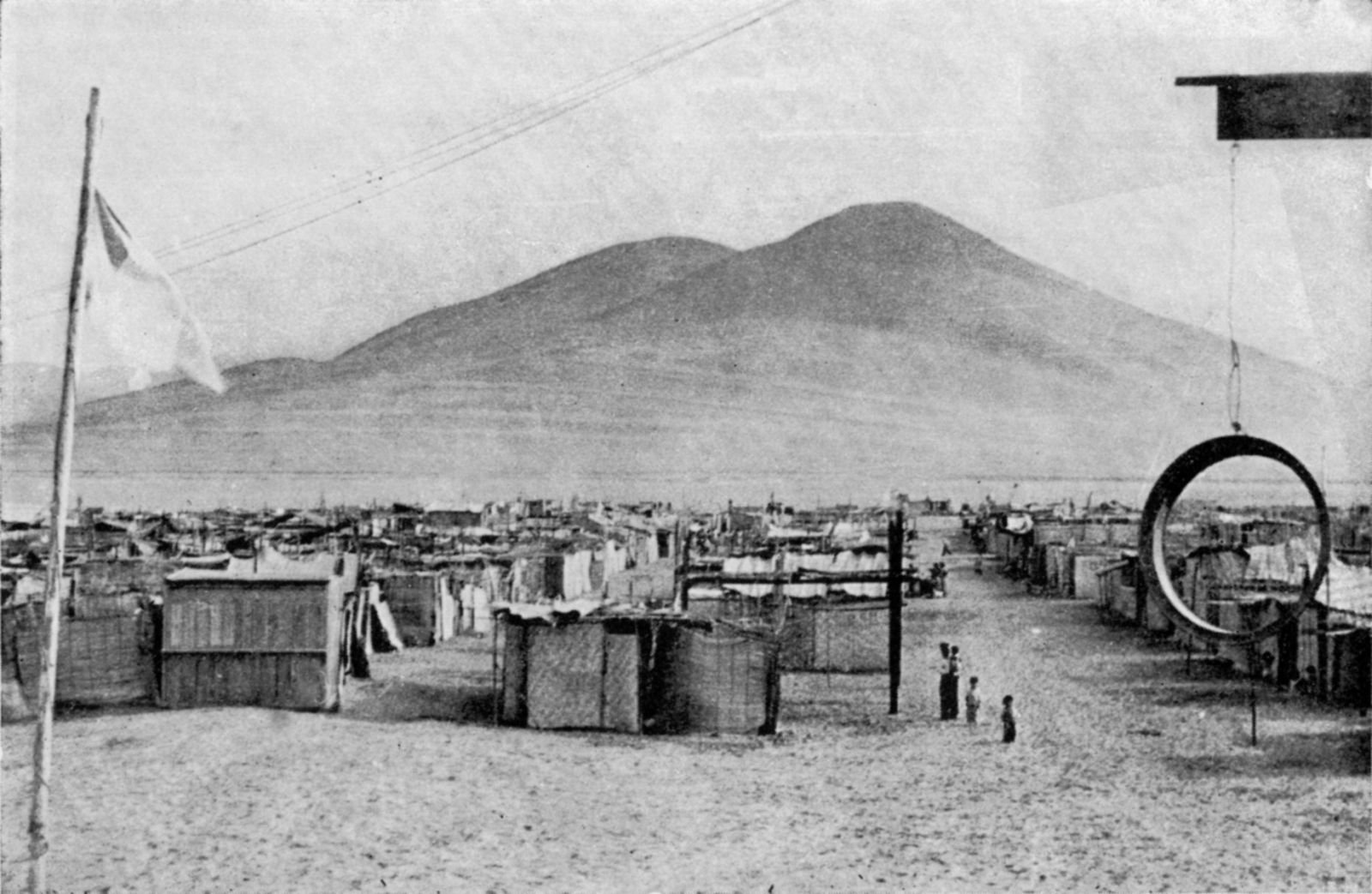

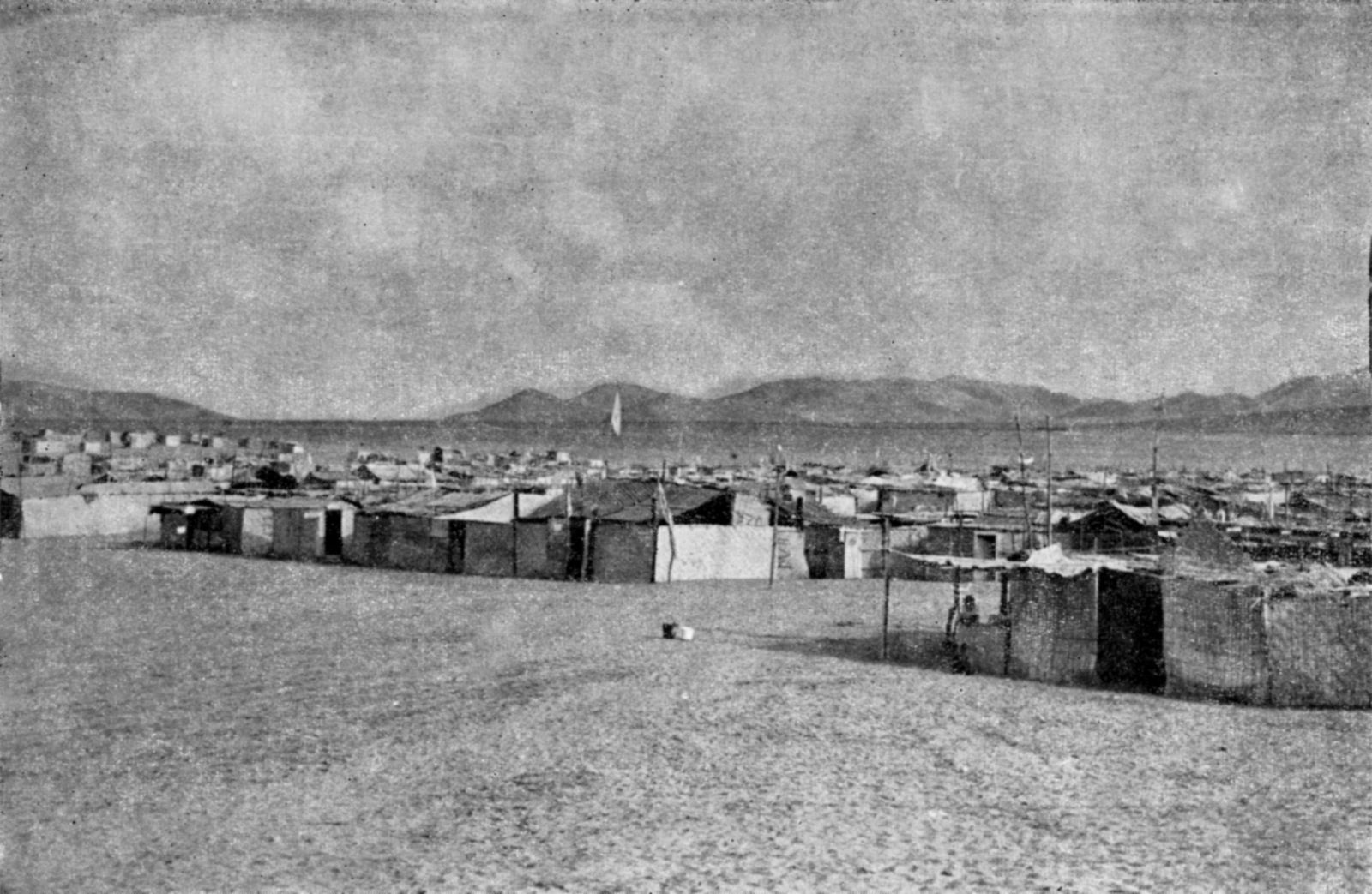

The establishment of the improvised ‘Ciudad de Dios’ (City of God) on Lima’s southern periphery, achieved through a large-scale land invasion on Christmas Eve 1954, dramatized the desperate nature of the capital’s housing crisis. Although this method of forming barriadas had proliferated over the previous half decade, the Ciudad de Dios invasion, involving 8,000 people, was by far the largest to date, testing the limits of the state’s tolerance for extrajudicial development and provoking it into a more assertive response. After initially insisting that Ciudad de Dios would be forcibly closed down, in 1955 the government turned to planning law to broker a solution, devising new guidelines that could better accommodate – but also more effectively regulate – these emerging patterns of urban development. This tactic culminated in 1961 with the comprehensive set of reforms advanced in Law 13517, which outlined a new approach to understanding and shaping the selfbuilt city. While prevailing urban planning techniques had failed, confidence remained that once its techniques were recalibrated in line with a revised regulatory framework, planning professionals would again be able to deliver rational and effective solutions to ‘channel’ urban growth. This article assesses how efforts to apply the new regulations unfolded and how they fared in practice.

In February 1961, President Manuel Prado signed Law 13517, describing it as ‘a work of public good, leading towards strengthening the family unit, reinforcing work habits, and securing a decent existence for our people’.3 A 1958 report had argued that the barrios marginales (marginal neighbourhoods, being ‘structured at the margins of the law’4) were undermining official property registers because so many ad hoc occupations of state land had not been properly recorded. Likewise, in cases involving private property, the extra-legal transfer of title by leaseholders (without the owner’s knowledge or permission) was blurring the threshold between fully authorized occupants and those who had gained residency through ‘irregular, violent, or clandestine tenancy’. Continued inaction by the state would only lend legitimacy to this situation, since over time, these ‘marginal’ arrangements would gain some legal protections, inevitably leading towards ‘the conversion of barriada property holders [poseedores] into property owners [propietarios]’; allowing this increasingly porous boundary – between legally owning land and merely occupying it – to dissolve altogether ‘would mean giving legality to chaos and abuse’.5 The framework of Law 13517 proposed two parallel approaches to solving this problem.

First, all existing barriadas would be given the opportunity to legalize their status, on the condition that their urban amenities were upgraded and that individual dwellings were rehabilitated to acceptable standards as defined by the law. Second, no new barriadas would be tolerated: instead, the government would establish its own ‘Urbanizaciones Populares de Interés Social’ (UPIS; Low-Income Social Housing Subdivisions), where housing would once again be self-built by residents, but construction would be closely supervised and conform to an approved urban plan. Both solutions were to be achieved with maximum economy of means on the part of the state, by making use of residents’ self-help labour, and by insisting that they cover the costs of technical assistance, urban upgrading, and purchasing their lots. The key difference between the two approaches was that the intervention of architects and planners occurred at different stages of the process: in the first case, after building had commenced, using a detailed site survey as the starting point for remodelling the barriada; in the second, development would be controlled from the outset, as self-build construction unfolded within an established framework. While elsewhere slum clearance remained the only conceivable response to unauthorized urban development, Peru’s Law 13517 proposed an innovative approach to shaping the evolution of the rapidly modernizing city – one that attempted to negotiate between ‘marginal’ self-generated construction and the dictates of official plans. With this legislation, the modernist imperative to shape urban space was not abandoned altogether, but found an alternative expression in these hybrid modes of urbanism.

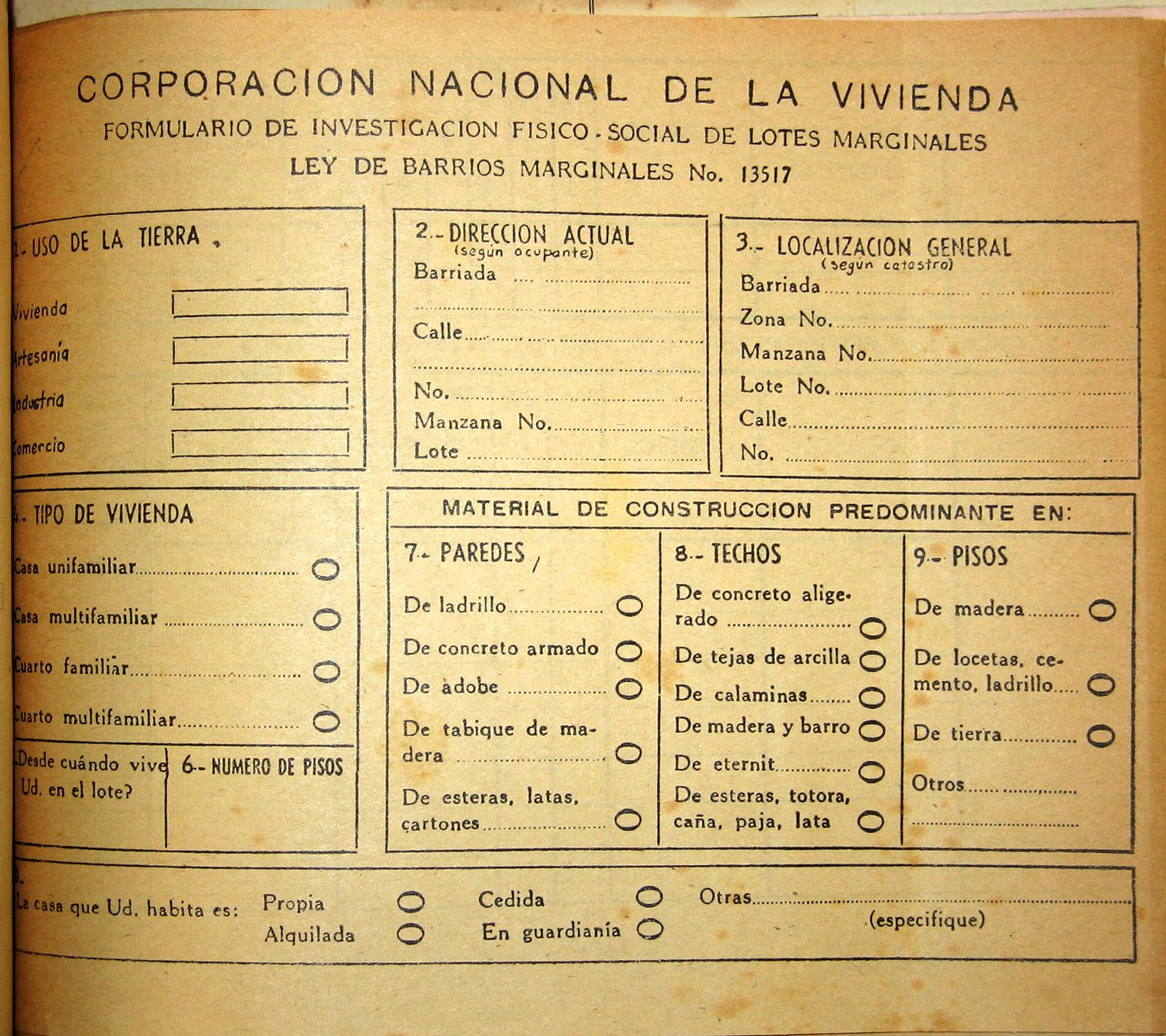

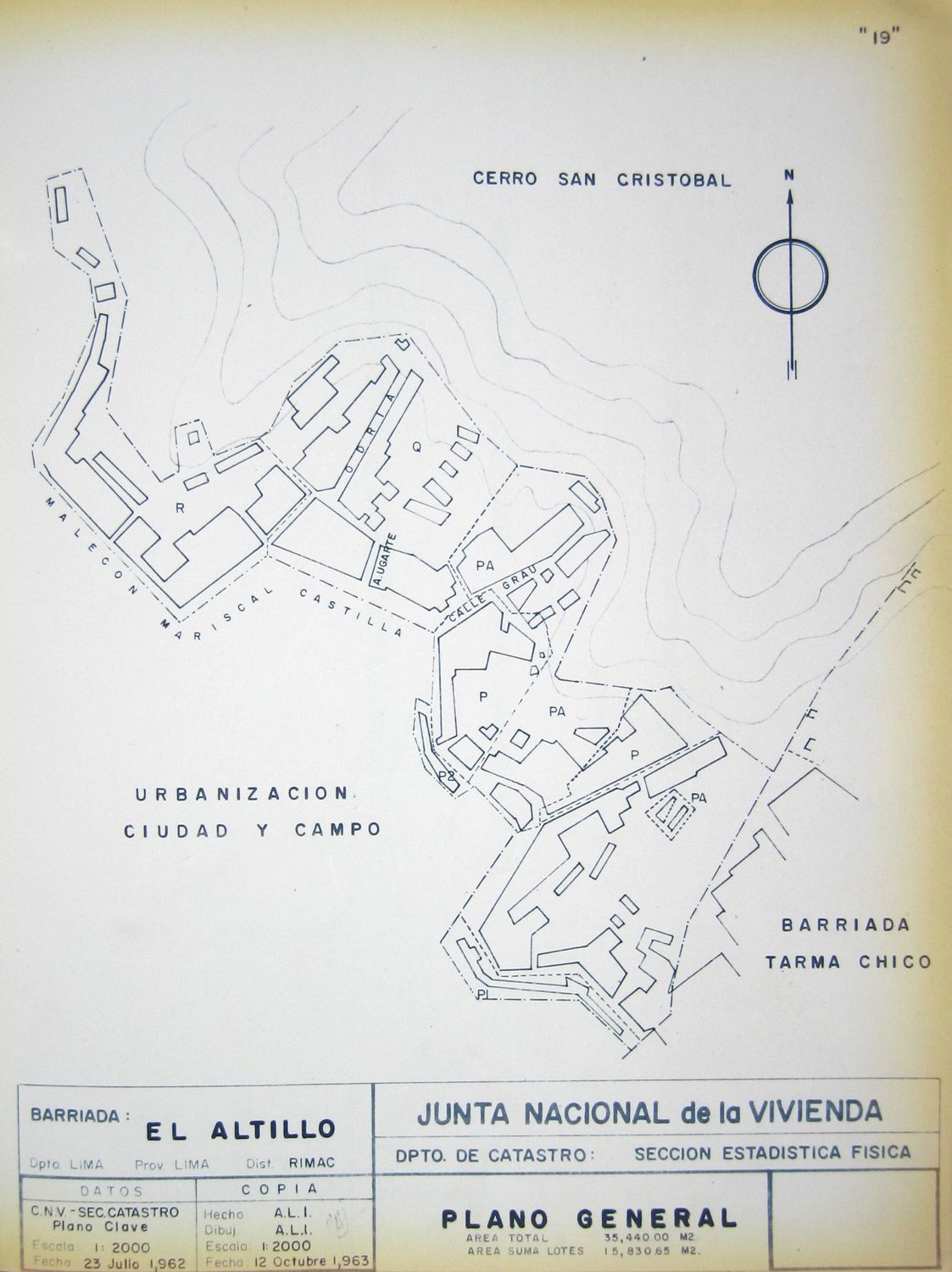

Implementation of Law 13517 began in April 1961 with a nationwide survey of all potential or suspected barrios marginales undertaken by the state housing agency, the Corporación Nacional de Vivienda (CNV). Completed a year later, the survey resulted in the declaration of 271 barrios marginales across Peru, 123 of them in greater Lima. In the next step, each settlement was to be classified as suitable for eradication or rehabilitation. Since rehabilitation involved not only physical improvements but also resolving disputes over the ownership of the settlement site and of individual lots, future viability would be determined by a panel of four experts: a public health professional, an urban planner, a sanitary engineer and a lawyer. Eradication would be mandatory if the settlement was adversely affecting ‘the normal growth of the city’; if it was too expensive or technically challenging to provide services; if the site was vulnerable to landslides or river erosion; or if the value of the land ‘does not justify building low-cost housing on it’.6 Clearly technical considerations were shaded by the politics of urban development.

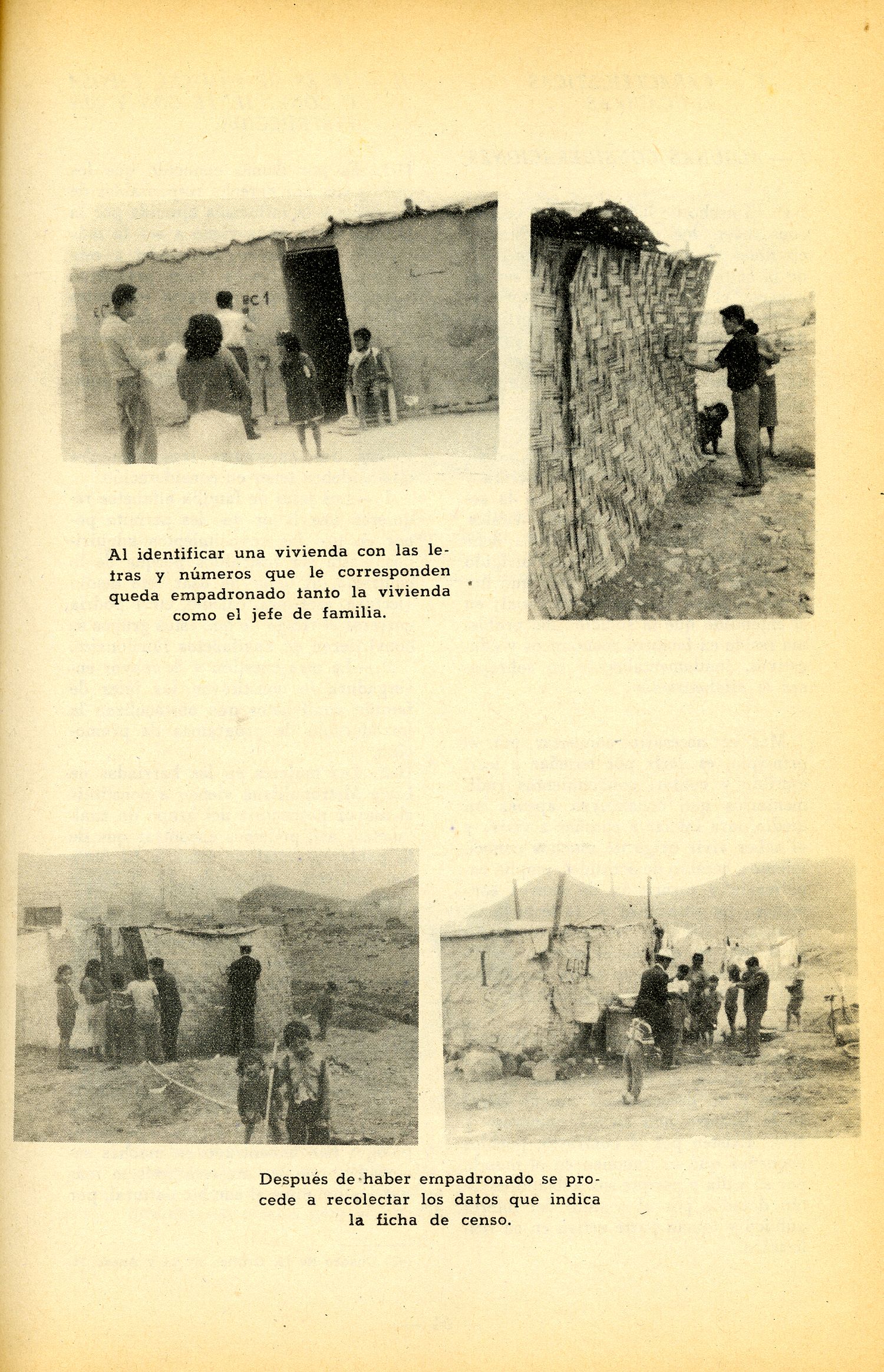

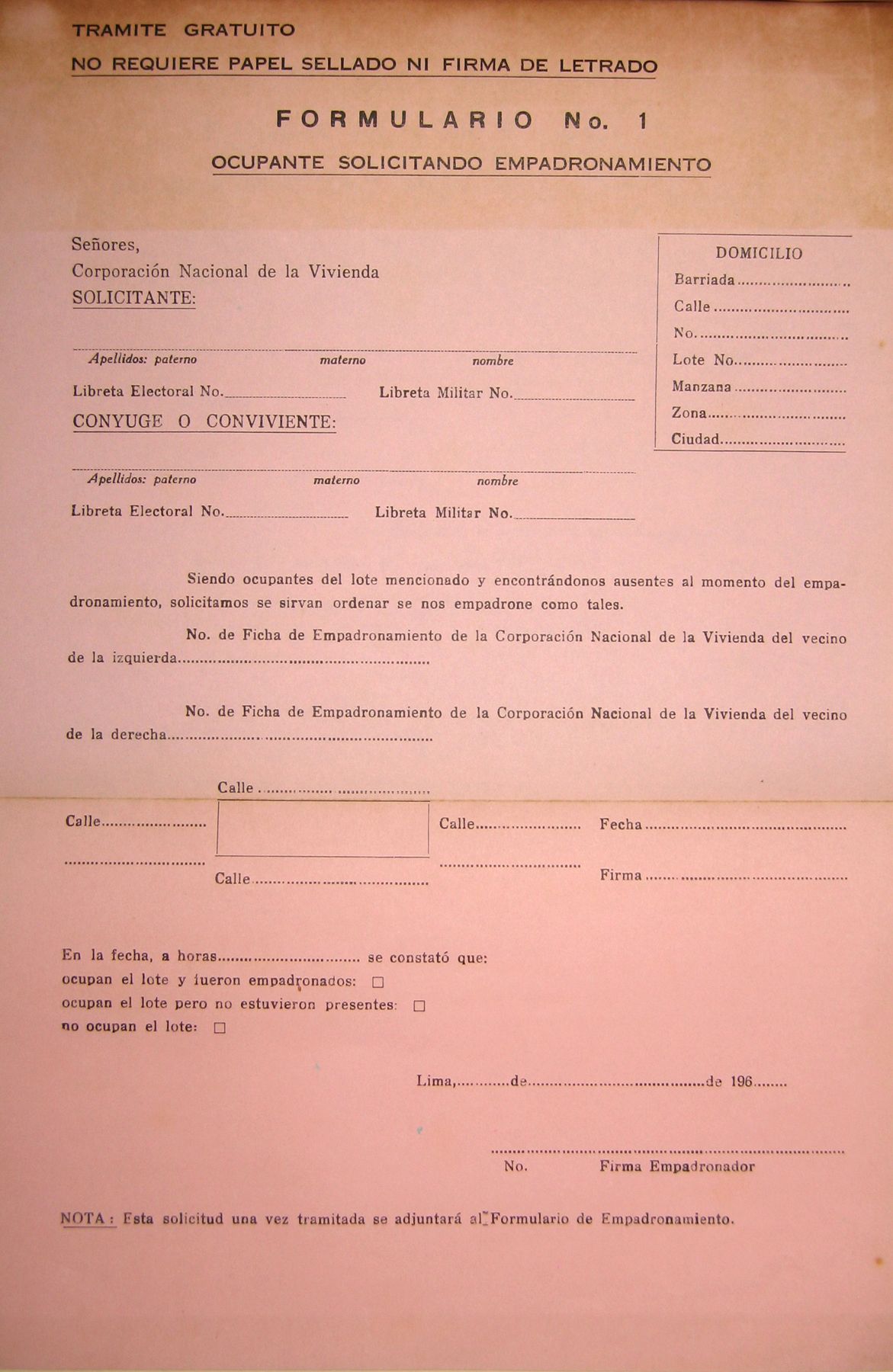

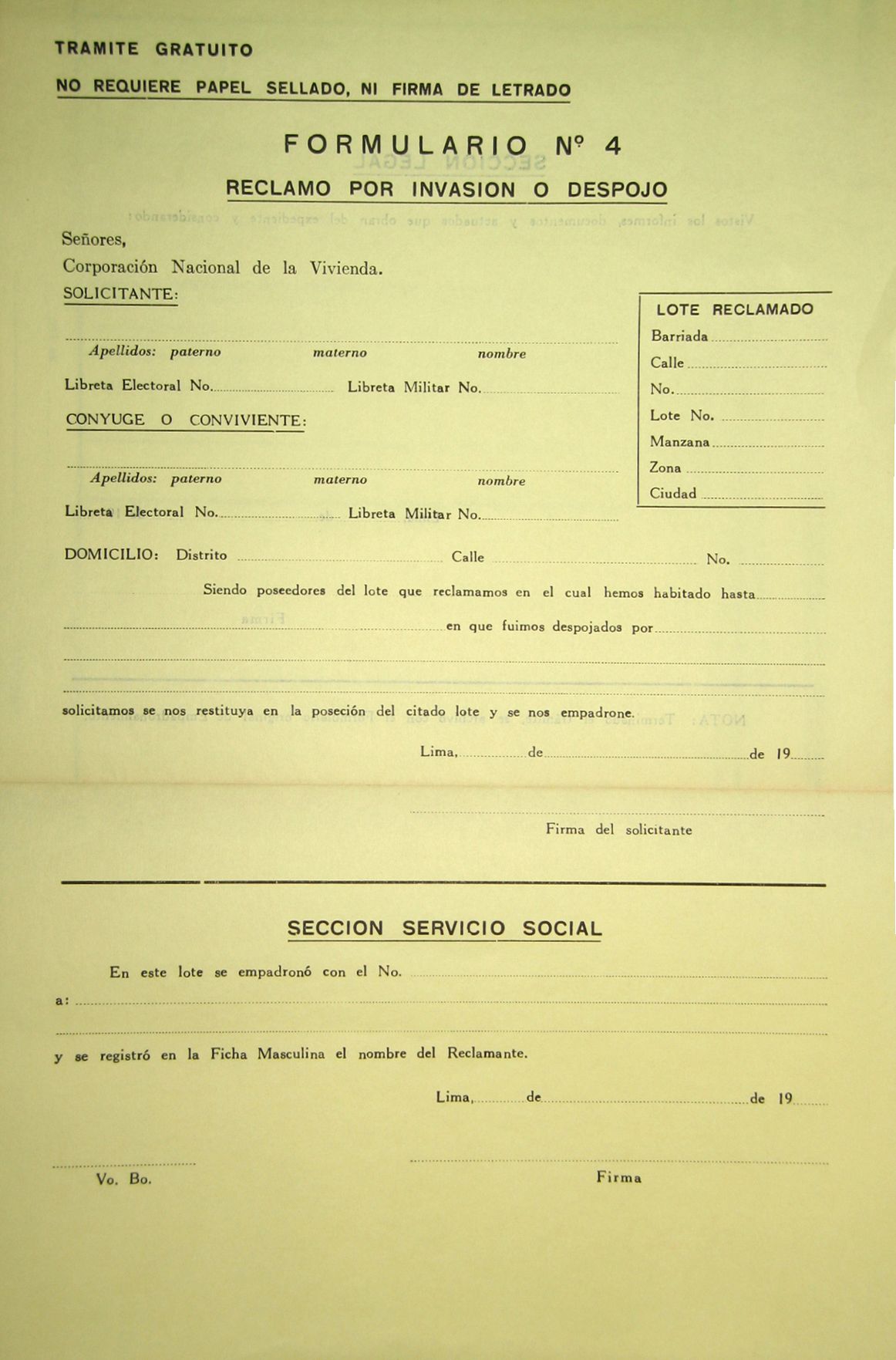

In the case of barriadas set for rehabilitation, the guidelines stipulated the provision of passable roadways, water and sewerage infrastructure, and a wide range of urban amenities, to be determined by the settlement’s size, location and population. At a minimum this meant schools, medical posts, churches, parks and sports fields, but it could also include workshops for small-scale industries and commercial centres. This approach was influenced by a government-commissioned report issued in 1958, which had presented an expanded definition of housing: ‘The dwelling embraces not only the house itself, but also the neighbourhood and the community, and generally the environment as a whole or habitat where man and his family develop their usual activities.’7 This definition consequently entailed a higher benchmark for an adequate ‘dwelling’ – now conceptualized as integrated into a wellappointed neighbourhood. A contemporaneous study had condemned the barriada not simply for its poor-quality housing, but more seriously because of its limited economic opportunities and inability to meet its own food supply, revealing it to be ‘a parasite city [ciudad parásito], which is reflected in the high cost of housing’.8 By contrast, the reformed neighbourhoods envisaged under Law 13517 echoed the model of the unidad vecinal (neighbourhood unit) – a self-sufficient city in miniature, circumscribed by green space and containing all necessary community facilities. This concept was introduced in Peru in the 1940s by architect (and later president) Fernando Belaúnde Terry, with influences leading back to Clarence Perry, and to projects such as Radburn and the New Deal Greenbelt towns.9es, 2004), 131.] The detailed workings of this process emerge in a brief report from May 1961 on the Plan Fray Martín de Porres remodelling project, covering 18 barriadas. As a first step, it was necessary to fulfil the requirements of Law 13157 for establishing ownership, an arduous fivepart process: 1) the empadronamiento – creating a register of residents, confirming their status as property holders, without conceding them property ownership; 2) the catastro (cadastral survey) – drawing up detailed plans of the settlements in order to determine the boundaries of each lot; 3) the ‘cleaning-up of the empadronamiento’ – identifying unoccupied or unclaimed lots, to be turned over to the CNV for siting urban amenities or for reassignment to other residents; 4) studying existing provisions for water and sewerage lines; and 5) developing plans to remodel individual lots that were too large, too small or irregular in shape. Following this, provisional title would be granted – a non-transferable, non-monetizable title, in order to counter land speculation – with residents given seven years to finish their dwellings to acceptable standards, and to complete payments for their individual lots as well as their share of upgrading costs for the settlement as a whole. Only then would residents gain full title to the property.

The logic behind this elaborate procedure was governed by the need to reinforce the existing property regime, underscoring the threshold between those who owned property, and those who had possession – or had taken possession – of it without proper authority. In the process, the legislation also reasserted the state’s right to police this boundary, to grant (or refuse) title and to legitimate possession. The aim was not to facilitate, or speed up, the process of gaining title but to clearly outline the requirements to pass from property ‘holder’ to property ‘owner’ – and to establish them as arduous, underscoring the fact that ownership was not a universal right, but a privilege to be earned: in this case, possession was not nine-tenths of the law, but merely the first rung on the bureaucratic ladder to recognized legal ownership. For the poseedor who did not have the means to purchase land through conventional property markets, a series of complementary investments would suffice: compliance with bureaucracy, expenditure of self-help labour, and at least a nominal payment.

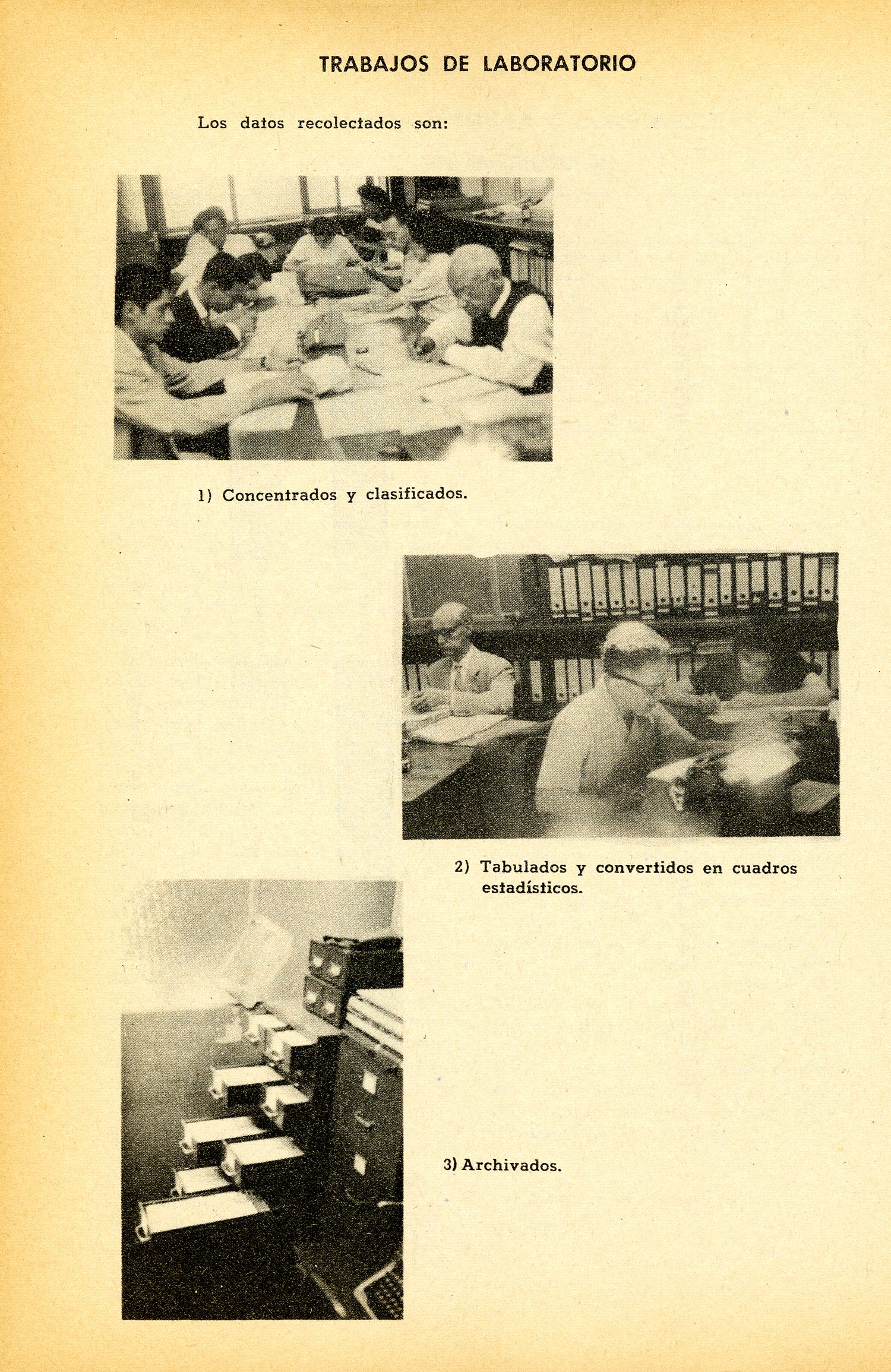

A vast amount of data was required to ascertain the nature and condition of each ‘marginal’ settlement – or the precise degree of each settlement’s marginality – in order to determine its fate with professional exactitude. Much of the CNV’s time was devoted to collecting and sorting through this data – cadastral surveys as well as demographic statistics to gauge the economic and organizational resources of the residents. With 271 barriadas nationwide, and an estimated population of 105,781 households,10 this was never going to be a fast process. Furthermore, when set against the reality of the ‘marginal’ city (outside the law, but obeying its own norms of improvised urbanism) the law faced a series of challenges that sharply defined the limits of its efficacy.

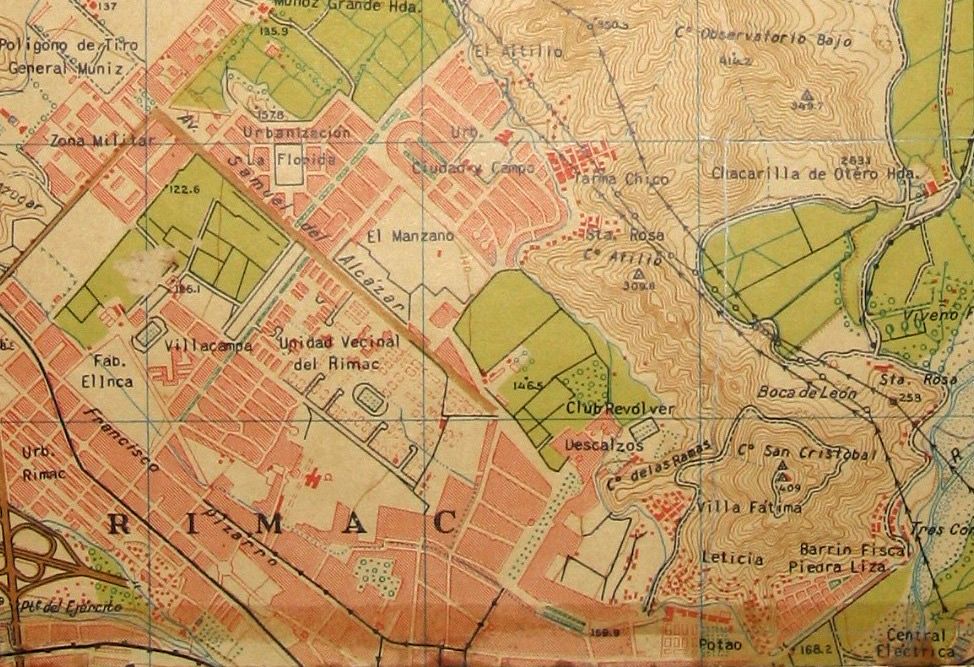

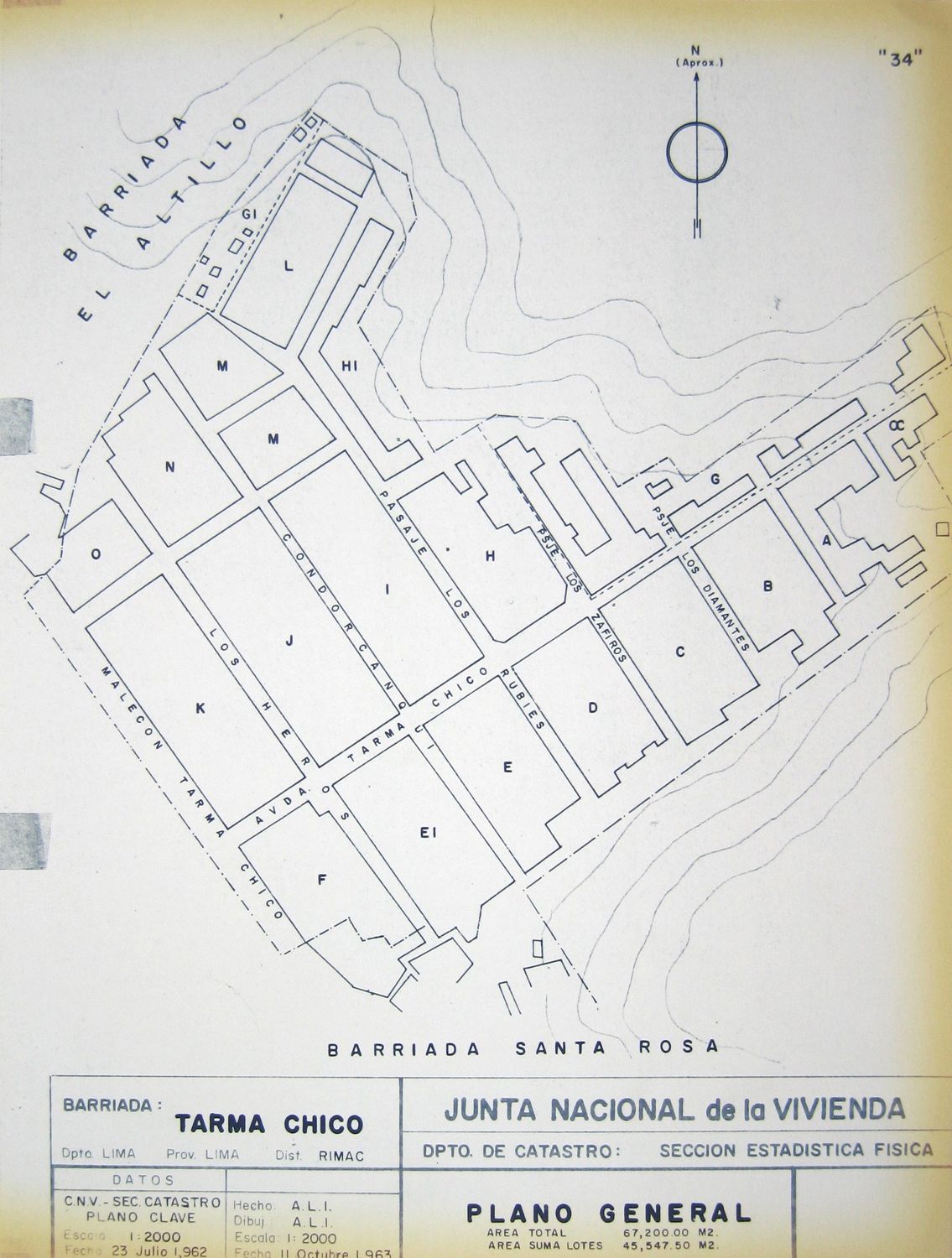

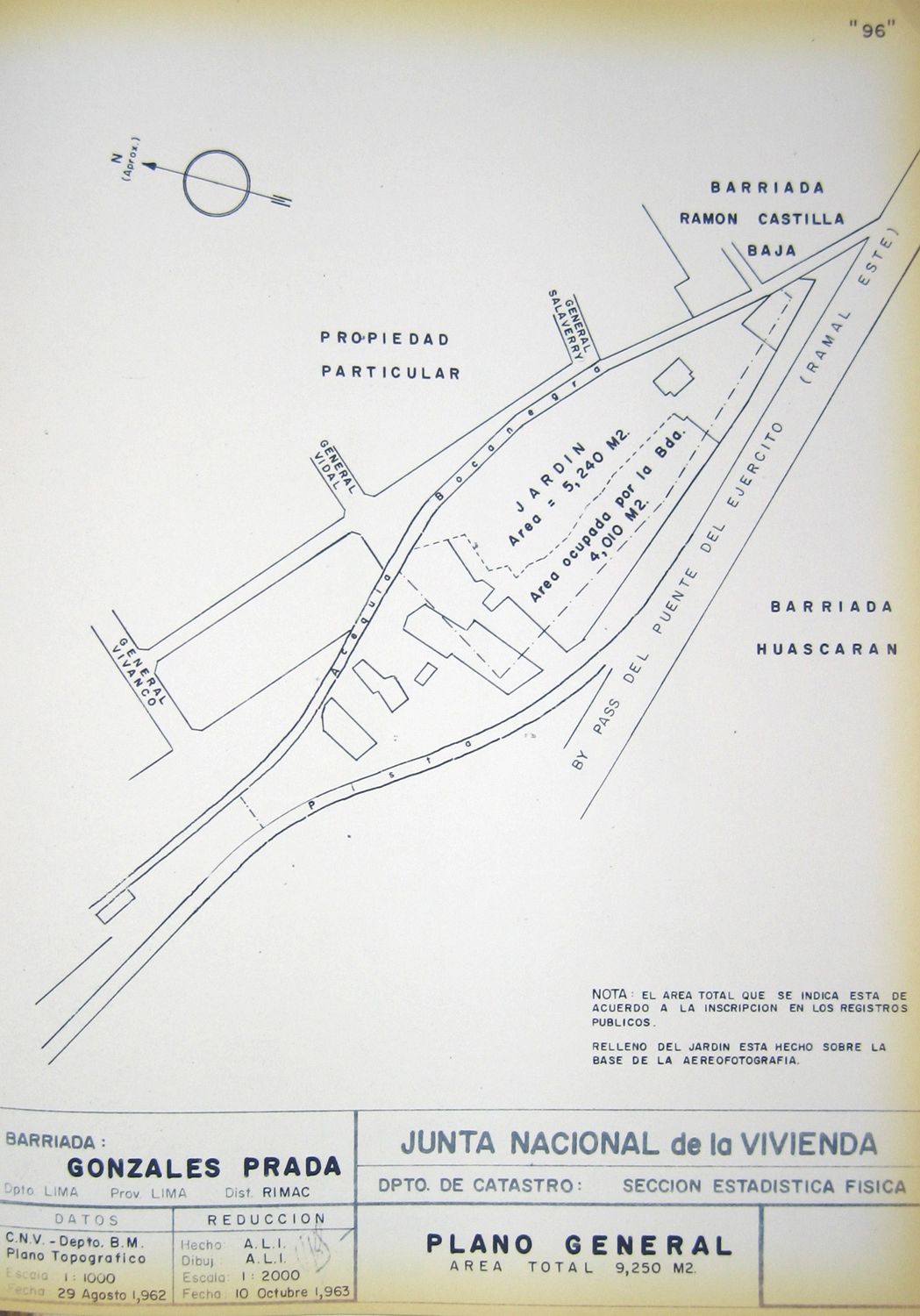

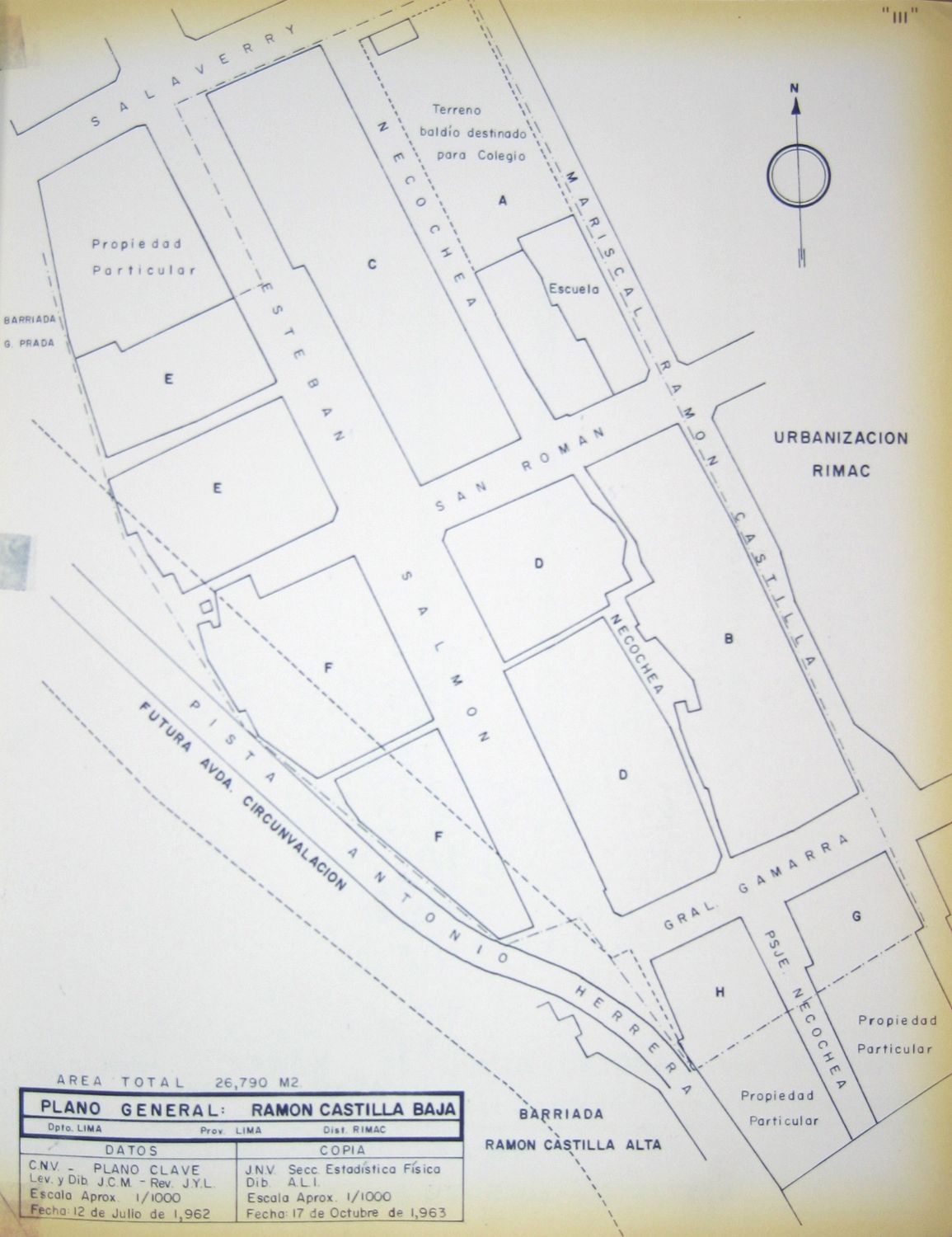

The tangled histories of those barriadas where the mandated studies were actually carried out demonstrate that the implementation of the law would be far less straightforward than the guidelines had suggested. Replacing the official maps that had included the barriadas as indeterminate outbreaks of red dots, the new cadastral surveys were decades ahead of other countries in rendering these patterns of urban settlement legible and thereby granting the most basic level of recognition. Yet their theodolitic precision masked competing claims of ownership and occupation that were complex and opaque, with invasions and illegalities by tenants equally matched by questionable acts on the part of landowners and real estate developers, and further confused by poor record keeping and uneven enforcement by the authorities. For example, the neighbouring sites of El Altillo and Tarma Chico both occupied state land, but while the first was quickly recognized under the law, the residents of the second were evicted to accommodate a shooting club, then allowed to return on the condition of paying land tax in lieu of rent; however, seeing that their neighbours in El Altillo lived rent-free, the residents of Tarma Chico stopped paying, leaving their legal situation tenuous. The residents of Gonzales Prada paid rent through an agreement with a private owner, but the local municipality now ruled this invalid, arguing that this ‘landlord’ had no right to the land since it actually belonged to the state. Finally, Ramon Castilla Baja was situated within a private subdivision, whose developer had been authorized to sell lots only once amenities had been installed; regardless, the developer had also sold sites that lacked services and furthermore had been earmarked for a public works project. These illegally established sections evolved through the letting and subletting of lots and the gradual invasion of any remaining open spaces: eventually, these tenants ‘had refused to continue paying rent, availing themselves of the benefits of Law 13517’.11

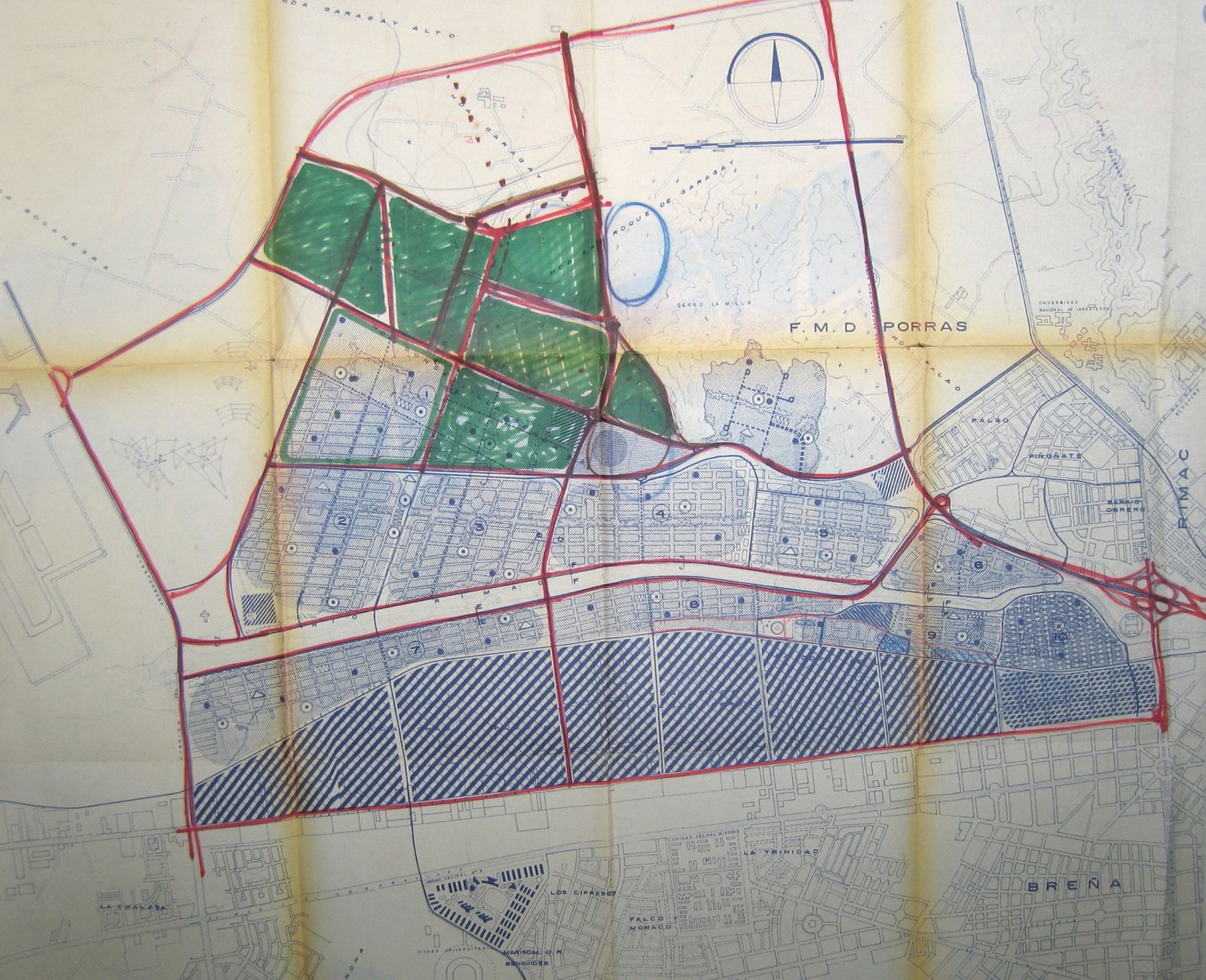

In this way the law revealed another of its limits: while each legislative reform vowed to enforce a cut-off date to benefit existing settlements and to criminalize the establishment of new ones, the slightest hope of securing decent, affordable housing inevitably intensified unauthorized construction. In the Río Rímac area in central Lima, between 1959 and 1961 the population increased from 50,000 to 120,000 – the growth being attributed to the promulgation of the new law, ‘since under the promise of a prompt attainment of property title, those who were living in other places in the urban area came to occupy its vacant lots’.12 The law operated as a system of solids and voids, creating the conditions for its evasion, as requirements and restrictions in one area created loopholes and incentives in another. The improvised city was by definition constantly shifting and evolving, without much regard for what had been planned for it. Nonetheless, despite these challenges – and despite the sense that data collection was endlessly postponing the construction projects that it was ostensibly laying the groundwork for – by early 1962 plans for the first remodelling projects and UPIS schemes were being drawn up.

Plan Río Rímac and Unidad Vecinal No. 6

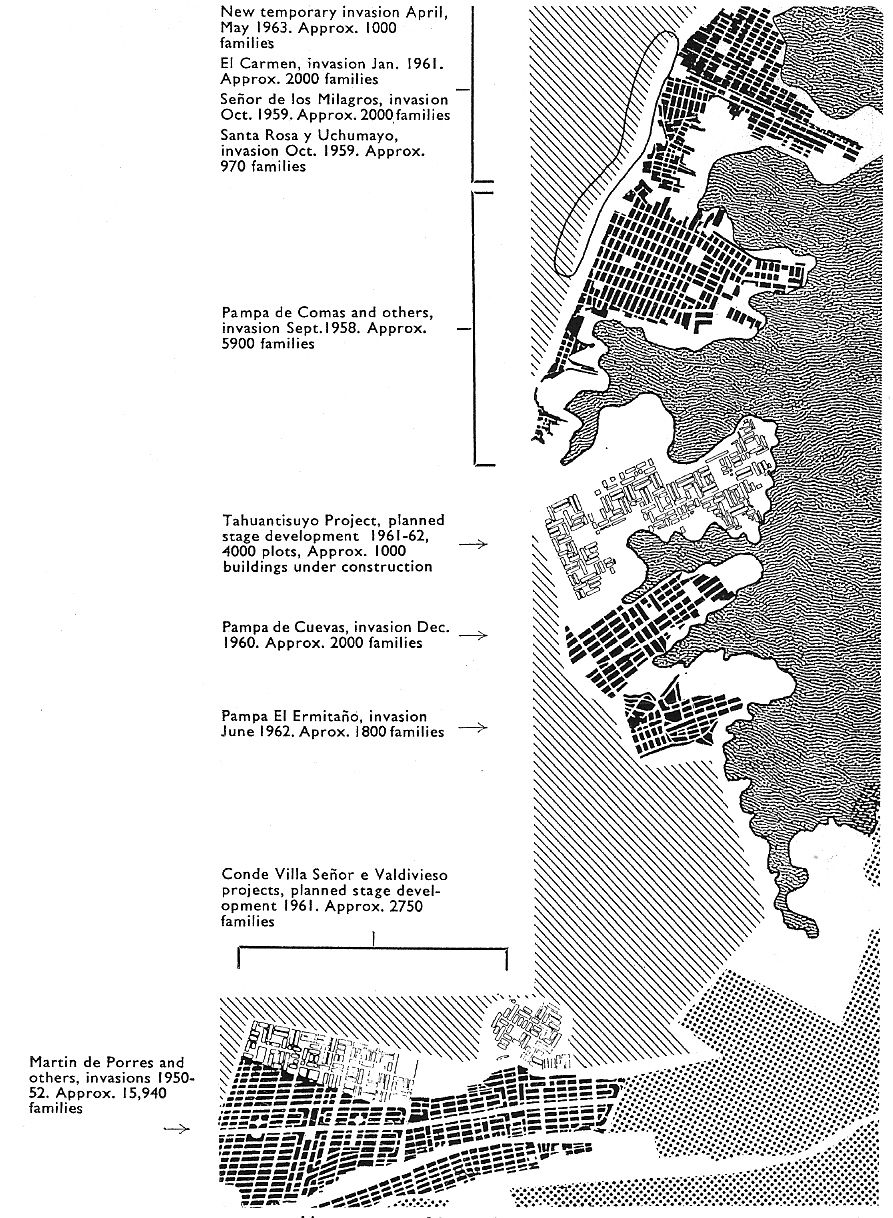

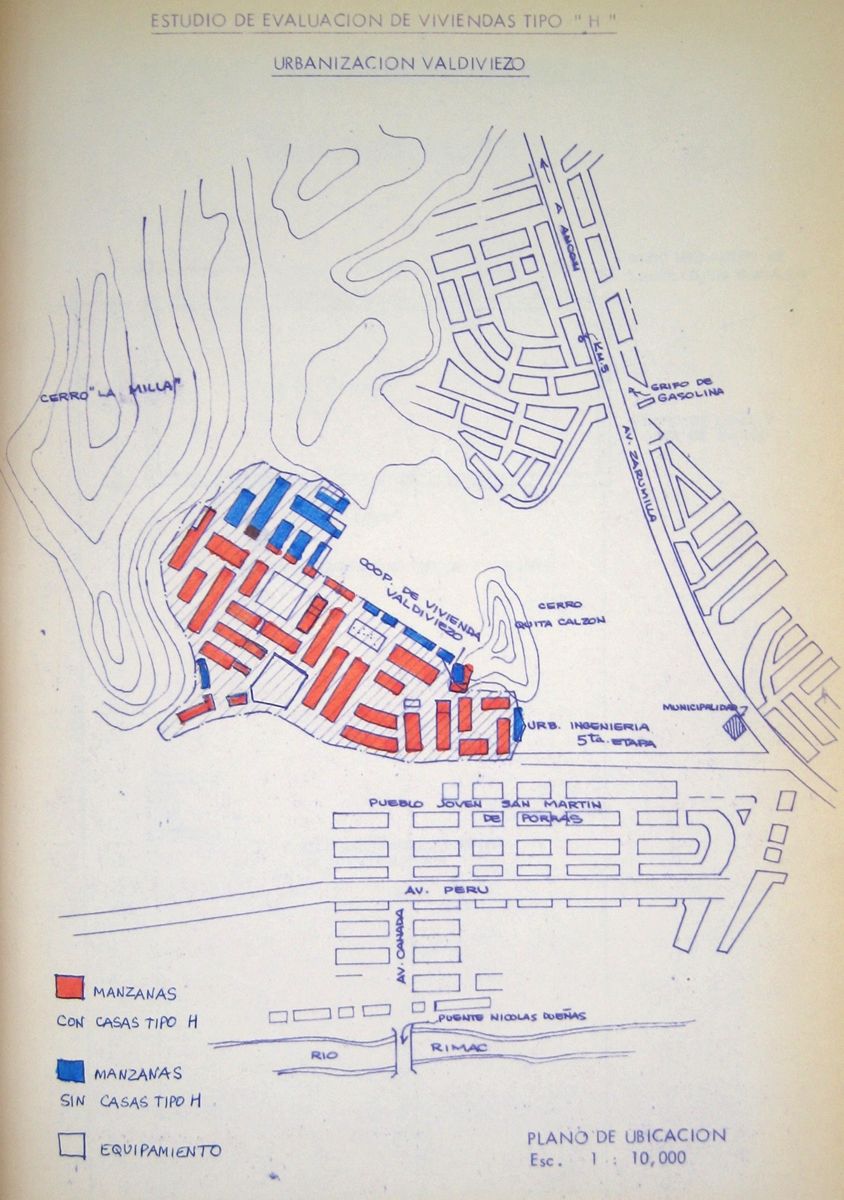

To begin the remodelling, the CNV divided Lima – and its 123 barrios marginales – into several zones, each of which required a new master plan. One of the first to be developed was Plan Río Rímac, covering an area close to the historical centre of the city and including over 30 barriadas on both sides of the river, with a combined population of 120,000. Plan Río Rímac called for rationalizing the existing barriadas into ten sectors – termed unidades vecinales – in preparation for their redevelopment, as well as the construction on adjacent unbuilt land of two UPIS projects (Hacienda Conde Villa Señor and Valdiviezo). The boundaries of the existing barriadas had been determined by the territory claimed by the various squatter settlement associations, and there were large differences in population density from one barriada to another, ranging from 233 to 450 inhabitants per hectare. While the plan sought to address this issue, any efforts to create a more ‘rational’ urban layout would have to contend with the specific histories of the barriadas and the social connections within (or tensions between) these different groups of residents.

The unidades vecinales of Plan Río Rímac, each assigned a population of 10,000 to 12,000 people, shared no formal or material qualities with a conventional neighbourhood unit, but the planning documents defined them in exactly the same terms, as urban units that were to be ‘self-sufficient in their primary needs’,13 as if the linguistic gesture of extending the category to include the re-formed barriada in itself contributed to its rehabilitation and integration into the norms of urban development. Plan Río Rímac listed services to be provided at the level of each unidad vecinal and others for the zone as a whole. Each unidad vecinal would have its own markets, neighbourhood civic centre and health post, while a main commercial zone, civic centre and a hospital were planned to serve the entire unidad vicinal. In addition, 57 kindergartens, 26 primary schools, four secondary or technical schools would be distributed throughout.

In the place of modernist ex nihilo development, Plan Río Rímac proposed that with prudent and timely guidance the unauthorized city could be more or less brought into line with established norms of urban planning. To this end the area’s existing barriadas would be rehabilitated through a series of measures: better integration with existing urban amenities, detailed – but minimally invasive – remodelling projects and the ‘eradication’ of housing when deemed necessary. As one example, all existing construction within the area designated as Unidad Vecinal No. 10 would be demolished, since it was chaotic and overcrowded, and its proximity to the city centre demanded high-density housing as a more appropriate use of the land, given its value. Families affected by these ‘eradications’ were to be re-housed in one of the two new UPIS projects – or ‘urban expansion areas’ – that were included in the plan.

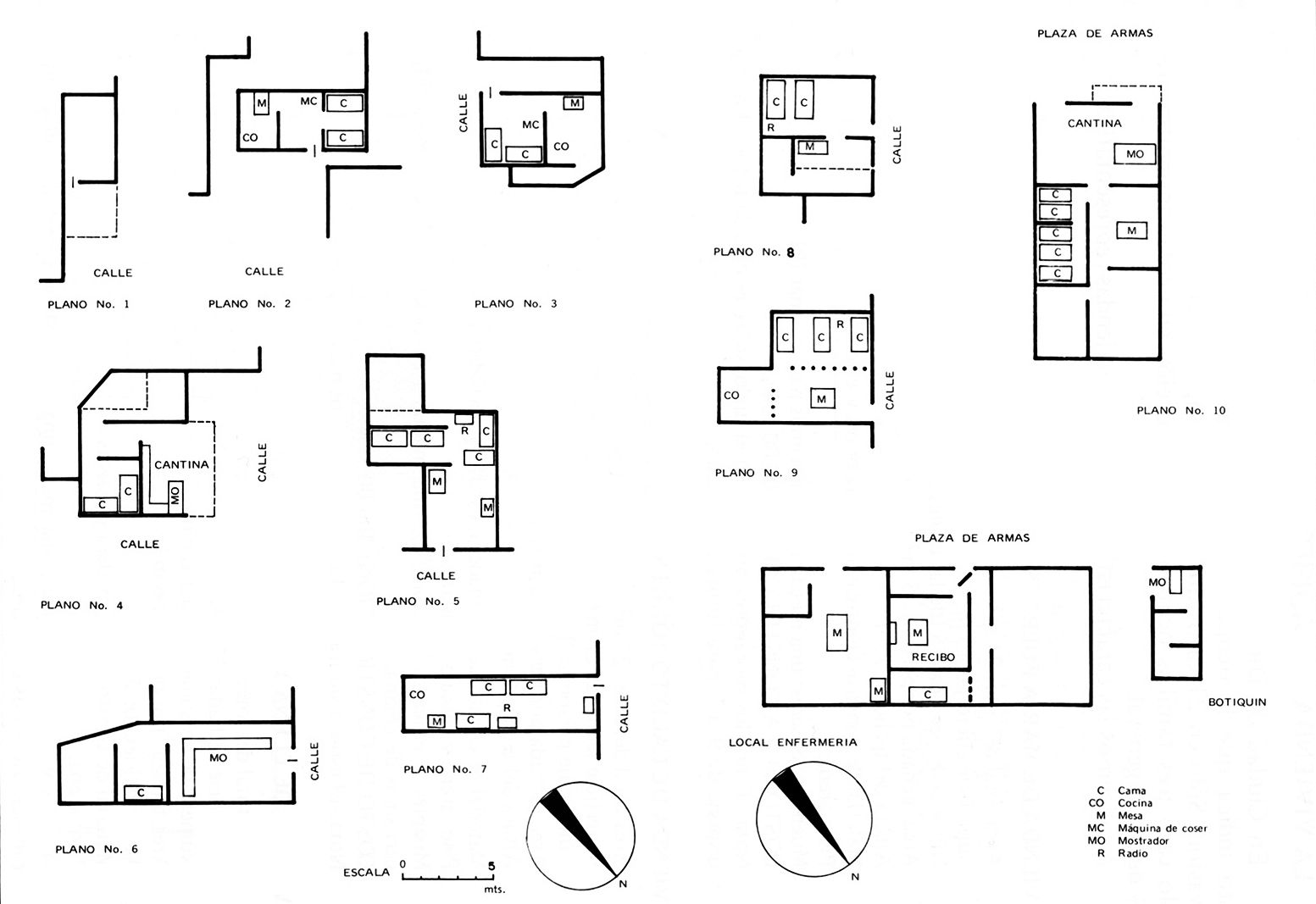

The detailed rehabilitation plan for Unidad Vecinal No. 6 of the Plan Río Rímac area provides an insight into how the approach was to be applied in the less problematic sectors.14 The existing housing was divided into three categories based on the quality of construction, the building materials and the appropriateness of the functional layout in terms of avoiding the ‘promiscuity’ of mixed uses (especially in relation to sleeping arrangements). An initial survey found that roughly 20 per cent of the dwellings were conservable, with 60 per cent suitable for rehabilitation and 17 per cent requiring demolition. On the urban level, two-thirds of the lots required remodelling because they were outside the stipulated size of 70 to 250 m2 or were irregularly shaped. In total, only 1,000 households would be able to remain on the same lot, while 395 were to be relocated, and 803 would have to be ‘eradicated’ from the area altogether – a measure required both to reduce the overall population density and to provide space for the additional amenities needed to convert the area into a self-sufficient unidad vecinal. Specifically, the newly-free space would be used for the construction of two schools (the key structuring element of the classic neighbourhood unit), with adjacent green space: one located at the end of a tree-lined boulevard and the other linked to a riverside walk. After calculating the costs per square metre of the remodelling, the project was determined to be viable – that is, the estimated monthly payment to be levied from each family, at 10 per cent of the average income, could be covered by the residents.

In summary: one unidad vecinal comprising six barriadas out of a total of 123 in greater Lima required a vast amount of detailed research and planning – carrying out the project and convincing residents of its value would require even more work. Furthermore, the amount of rehabilitation needed would likely be far higher in other areas, since Unidad Vecinal No. 6 was selected as an ideal site for a trial project, housing a relatively stable workforce earning a decent income, including barriadas formed by public sector employees from the Ministry of Development and the Police Cooperative.

UPIS: Hacienda Conde Villa Señor, Valdiviezo and Caja de Agua

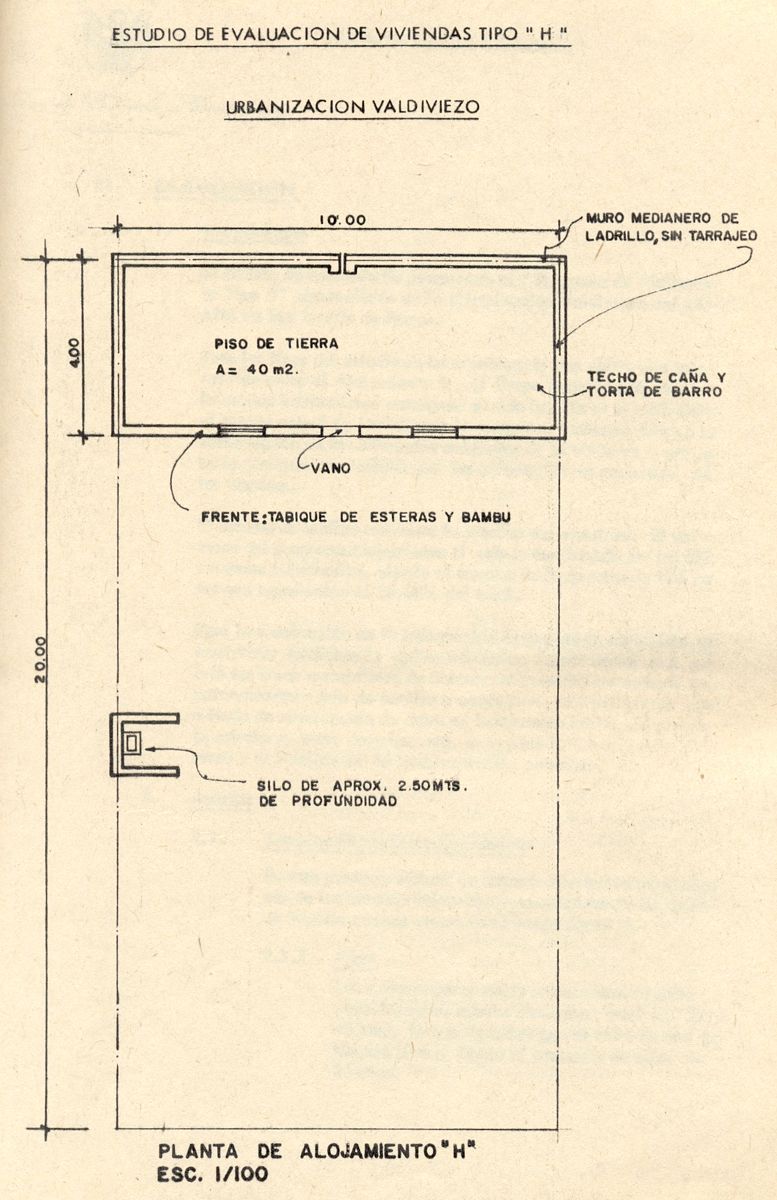

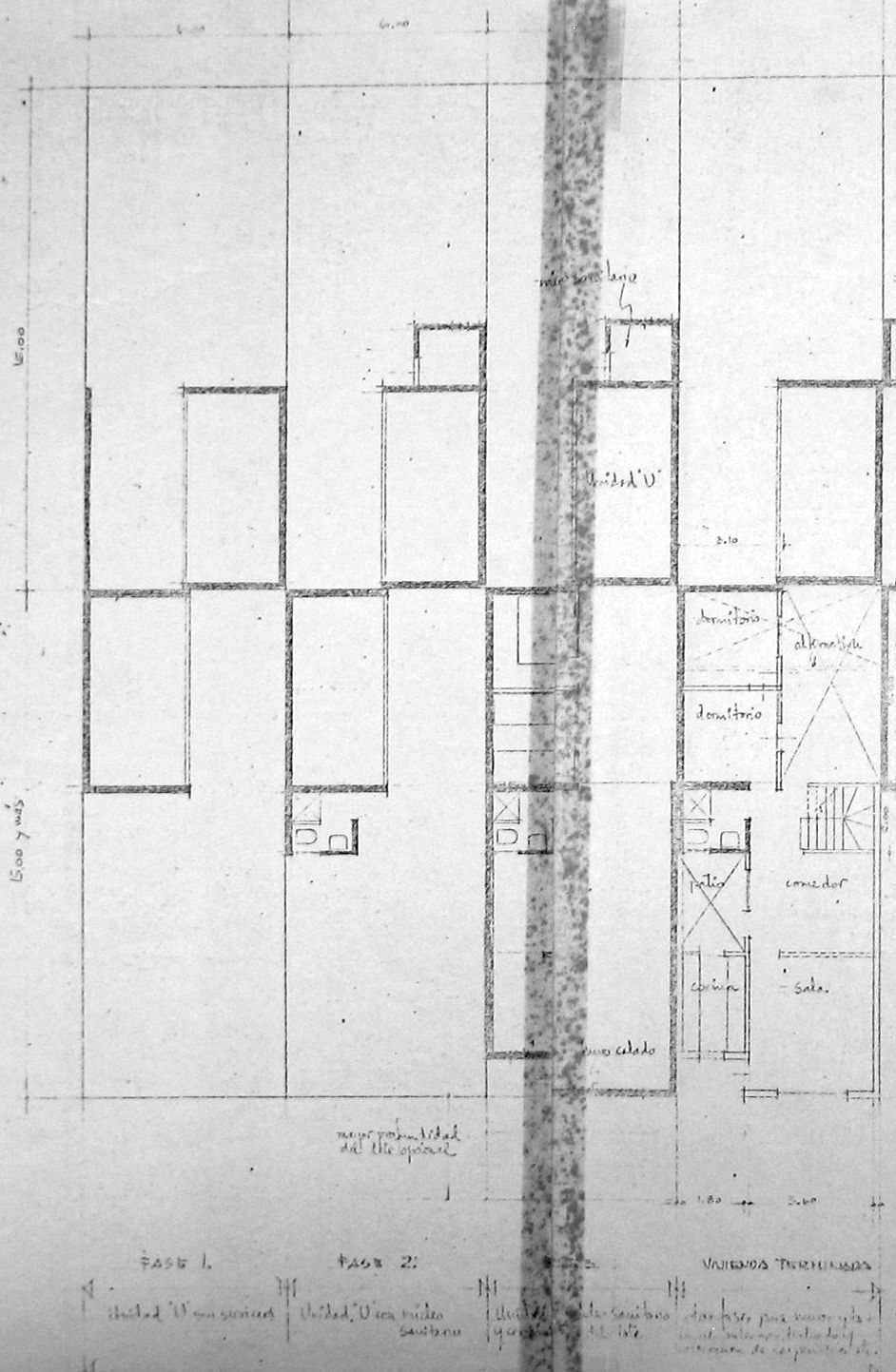

The families ‘eradicated’ by the remodelling in the Plan Río Rímac area were to be rehoused in nearby UPIS projects: Hacienda Conde Villa Señor, with 2,000 lots, and Valdiviezo, with 557 lots, were each to form a new unidad vecinal.15 In each case, the key structuring element of the plan was again the location of the various kindergartens and schools, sited to minimize the distance children would have to walk. In order to reduce costs these settlements initially had no electricity, no domestic water or sewerage system – only a waste silo in the middle of the lot. The services were installed a couple of years later, organized and financed by the residents themselves.16 Only a very basic shelter was provided: located at the back of the 10 x 20-m lot, a single room was constructed measuring 10 x 4 m, with party walls of brick at the back and on each side; the front of the dwelling was a thin partition wall of matting and bamboo, and the roof was of cane and clay. It was expected that residents would gradually develop their houses, moving towards the front of the lot; in the final stage the initial ‘primitive roofed area’ was intended to become an open patio framed by boundary walls.

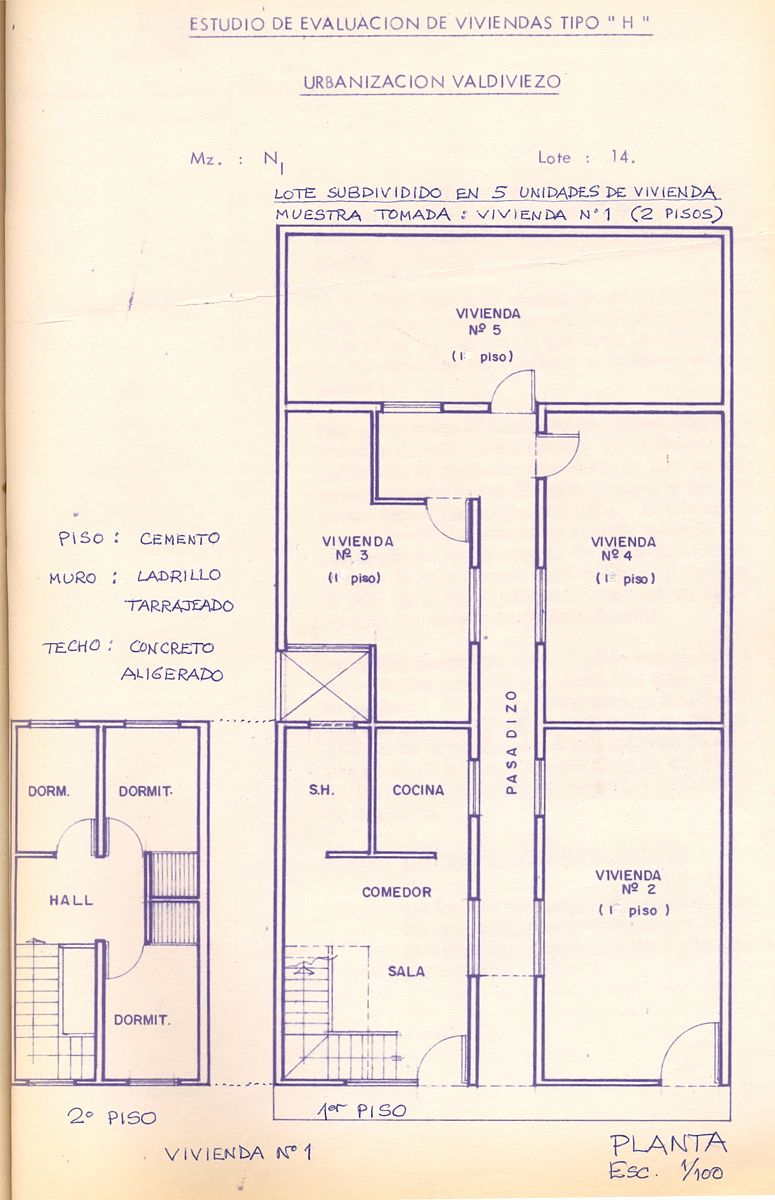

An evaluation report after 20 years of occupancy found that 45 per cent of residents had completed their dwellings, building three or more bedrooms to house an average family of eight; in one case the space had been subdivided into five dwellings (presumably for rental income); however many others were still in the process of building. Since the programme had been structured for the acquisition of the dwelling through the rental-sale system, all the residents became property owners after ten years. Although they had apparently been given construction plans for a permanent house considered suitable for their needs, it seemed that few, if any, had used them, ‘and not having been offered a program of technical assistance, they developed their house freely’.17 The report concluded that as a result at least 28 per cent of the resources invested had led to poor results, measured against the standards of conventional modernist housing. For example, one family had built windowless rooms for a living space and a bedroom, and many others had eliminated the planned patio and other open spaces in favour of additional living space. Finally, the evaluation report recommended a revised layout for future use: in the original design, the built walls of each pair of back-to-back dwellings formed a broad H; in the proposed revision the wide U of each basic unit was sited perpendicular to the back of the lot, avoiding the use of party walls and thereby allowing each household greater flexibility in their future construction plans.18

In the August 1963 issue of Architectural Design, architect John Turner offered a largely positive assessment of these ‘planned squatter settlement’ projects: they followed ‘the traditional and economically logical process of the barriadas themselves – but with very important improvements: the lay-out is far better, the plots more regular, there is a minimum supply of drinking water at the start’. The ‘ultimate value’ of the residents’ investment of money, time and labour in their houses was, Turner concluded, ‘guaranteed by the planning and controls exercised by the agency’.19

Other contemporaneous UPIS projects offered a more substantial minimum unit. At UPIS Caja de Agua (1964), planned as a relocation settlement following the eradication of the Cantagallo barriada, a permanent structure was offered, with one or two bedrooms, along with electricity, water and sewerage systems. This core was planned to develop gradually into a complete house, with a generous amount of open space for patios and a front garden. (Meanwhile, 103 Cantagallo families who were disqualified for failing to meet the UPIS project’s income requirements were given sheets of bamboo matting and offered a site further from the centre of the city to construct their provisional shelters anew.)20 In the end, as at Valdiviezo, due to the lack of technical assistance ‘the development of the house was left to the complete initiative of the recipient’21and many residents chose to sacrifice the planned open spaces to create additional rooms, or extended towards the street, incorporating the intended front setback into the body of the house. These were not the improved dwellings envisaged in Law 13517.

Plan Carabayllo

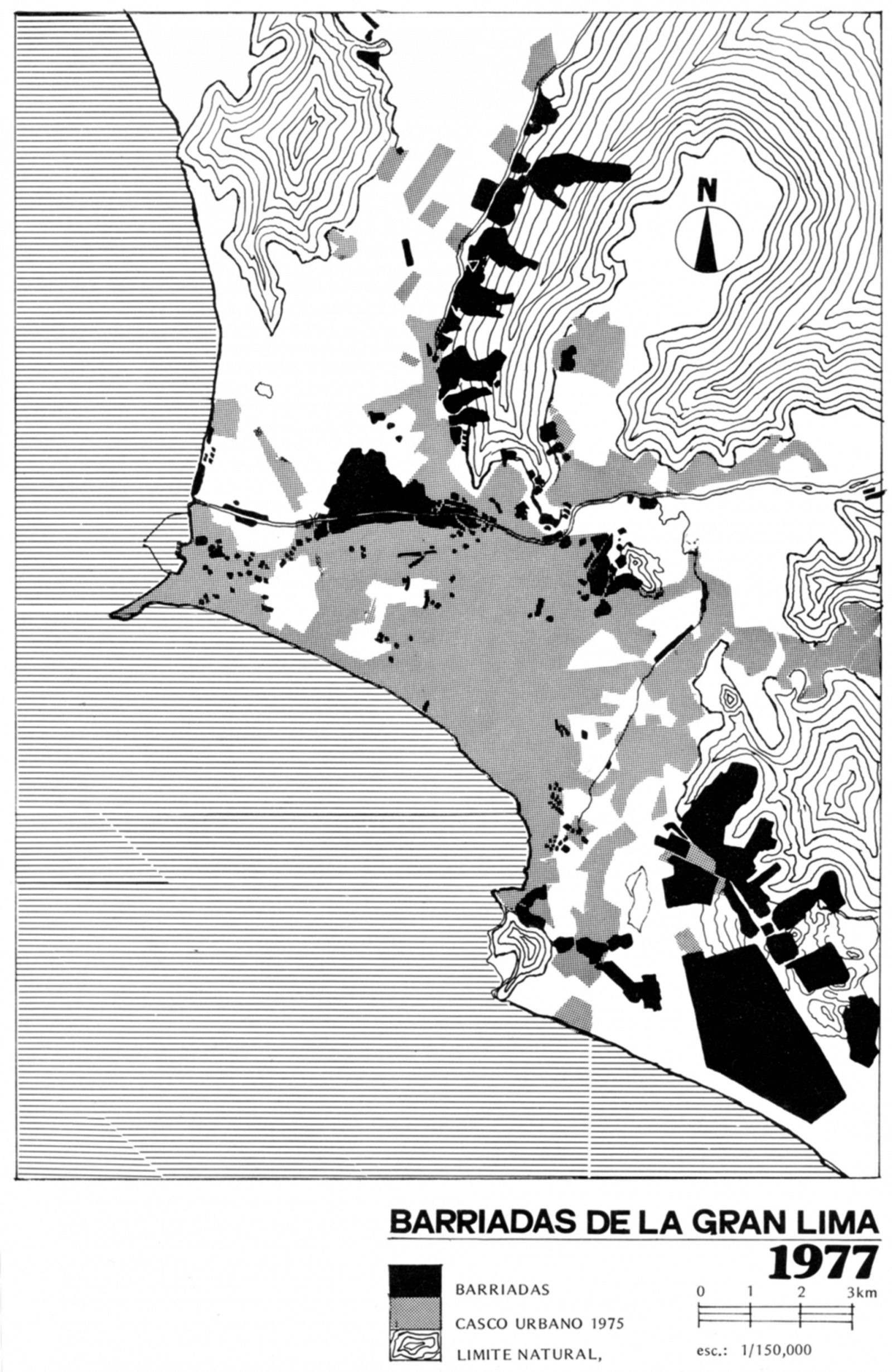

While Plan Río Rímac covered long-standing working-class districts close to the centre of Lima, other CNV plans responded to expansion on the city’s periphery. Law 13517 had excluded any barriadas established after September 1960 from its benefits, hoping to stop further unauthorized settlements. However, invasions in the northern desert plains around the foothills in Comas, which had begun in 1958, continued unabated; by 1963 the half-dozen barriadas in the area had a combined population of 100,000.22 The CNV produced modification schemes for some of these incipient barriadas and a master plan for the entire zone: Plan Carabayllo included schematic layouts for each of these (already occupied) zones of flat desert land, beginning with outlining a main access road for each settlement and a network of subsidiary streets. Even the smallest settlement zone (Pampa del Ermitaño) had sites set aside for children’s playgrounds and primary schools, while mediumscale settlements (such as the neighbouring Pampa de Cueva) were also allocated a local civic centre and park space. Envisaging an integrated plan to develop the entire area, Plan Carabayllo proposed multifamily housing, commercial and industrial areas for the largest settlements. It promised that with early intervention these incipient barriadas could be transformed into a series of ‘planned squatter settlements’ within a logical and efficient master plan.

Once again, John Turner discussed these projects in Architectural Design, endorsing their hybrid model of urbanism, because invasiondriven urbanism via ‘unaided or help-yourself methods’ could not be allowed to continue without intervention by planning professionals: ‘Something has to be done about it if there is not to be a total collapse of organized city development.’23 As an example of a positive intervention, Turner cited Urbanización Popular Tahuantisuyo, a Comas site with 4,000 plots where the CNV had ‘managed to control the invasion’ and convince residents to accept official management of the settlement’s planning and growth. Turner concluded that the state’s role should be precisely this: ‘To direct and co-ordinate existing forces and resources (and not to abandon them to create havoc or attempt to replace them).’ This could be best achieved through large-scale planned projects provided with basic services, seen as the next logical step from the UPIS model employed at Valdiviezo and Conde Villa Señor:

The final step, of course, is for the government to adopt this system as a general policy, acquiring land on the necessary scale and allowing its occupancy with an absolute minimum of utilities and then following up with the full set once the occupiers are well enough established.24

The funds needed to achieve this never materialized: following these first trial projects, the state committed few additional resources to implement Law 13517. While the law had appeared to offer a clear path to normalizing unauthorized development, in the absence of funding its elaborate bureaucratic framework provided only an illusion of control. In a sense, Law 13517 was at once too ambitious, given the financial and human resources that would be required to properly implement it, yet not ambitious enough, since it was quickly overwhelmed by the pace of unauthorized urbanization. It was also hampered by some questionable assumptions concerning the level of financial contribution that residents could manage, and the ease of organizing such projects on the human as well as the technical level. This was especially true with rehabilitation projects such as Unidad Vecinal No. 6, which do not seem to have progressed far beyond the preliminary planning stage – perhaps inevitable given the difficulties of convincing settled residents of the programme’s merits and positive cost-benefit versus the disruptions and expenses of ‘eradication’ or mandatory upgrading. The ‘tabula rasa’ approach was ultimately easier to implement, but even so only a handful of UPIS projects were realized. The question of how much could have been achieved with more time and government support is impossible to answer, since political shifts soon brought dramatic changes in the direction of housing policy.

Meanwhile, the ‘invaders’ continued to arrive, claiming their part in the city from its margins. The question of how they would be incorporated into the city; how their settlements would become part of the city; how controlled the assimilation of their city into the planned city would be, remained unresolved.

-

1Oficina Nacional de Planeamiento y Urbanismo, Lima: Plan Piloto (Lima: ONPU, April 1949). The plan was produced under the direction of Luis Dorich, the first Peruvian architect to formally study urban planning, completing his studies at MIT in 1944. Josep Lluís Sert and Paul Lester Wiener’s unrealized project for a new civic centre for Lima was one component of the Plan Piloto.

-

2ONPU, Lima Metropolitana: Algunos aspectos de su expediente urbano y soluciones parciales y varias (Lima: ONPU, December 1954), 5, 8.

-

3Ley de Remodelación, Saneamiento y Legalización de los barrios marginales (Lima: Corporación Nacional de la Vivienda, February 1961), 8.

-

4Fondo Nacional de Salud y Bienestar Social, La asistencia técnica a la vivienda y el problema de barriadas marginales (Lima: FNSBS, 13 November 1958), 8.

-

5Ibid., 10, 11.

-

6‘Reglamento de la Ley No. 13517’ (21 July 1961), in: Lima: Historia y urbanismo en cifras (Lima: Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento, 2004), 436.

-

7Comisión para la Reforma Agraria y la Vivienda, Informe sobre la vivienda en el Perú (Lima: CRAV, 1958), 307.

-

8FNSBS, La asistencia técnica, op. cit. (note 4), 51.

-

9Wiley Ludeña Urquizo, ‘Fernando Belaúnde Terry o los inicios del urbanismo moderno en el Perú’, in: Tres buenos tigres: vanguardia y urbanismo en el Perú del siglo XX (Huancayo; Lima: Ur[b

-

10Corporación Nacional de Vivienda, Información básica sobre barrios marginales en la república del Perú (Lima: CNV, 1962), 212.

-

11Junta Nacional de la Vivienda, Datos estadisticos de los Barrios Marginales de Lima: Distrito del Rímac, Vol. 1 (Lima: JNV, December 1963), 22, 37, 99, 114.

-

12CNV, Plan Río Rímac: Memoria Descriptiva (Lima: CNV, February 1962), 5.

-

13Ibid., 12.

-

14CNV, Plan Río Rímac – Remodelación de la Zona 6 (Lima: CNV, September 1962).

-

15CNV, Plan Río Rímac – Anteproyecto de Urbanización Popular de la Hacienda Conde Villa Señor: Memoria Descriptiva (Lima: CNV, December 1961).

-

16Ministerio de Vivienda, Evaluación técnica y social del programa ‘Alojamiento H’ en la Urbanización Valdiviezo (Lima: Ministerio de Vivienda, 1980-1981).

-

17Ibid.

-

18Ibid.

-

19John F. C. Turner, ‘Minimal Government- Aided Settlements: Valdivieso and Condevilla Señor Barriadas, Lima, Peru,’ Architectural Design, vol. 33 (1963) no. 8, 379.

-

20Ministerio de Vivienda, Evaluación de un proyecto de vivienda: Evaluación integral del proyecto de vivienda Caja de Agua-Chacarilla de Otero (Lima: Ministerio de Vivienda, 1970), 49.

-

21Ibid., 162.

-

22John F. C. Turner, ‘Lima Barriadas Today,’ Architectural Design, vol. 33 (1963) no. 8, 375.

-

23John F. C. Turner, ‘Barriada Integration and Development: A Government Program in San Martín, Lima,’ Architectural Design, vol. 33 (1963) no. 8, 377.

-

24Turner, ‘Minimal Government-Aided Settlements’, op. cit. (note 19), 379.

Source: John F. C. Turner, ‘Lima Barriadas Today’, in: Architectural Design 33, no 8 (August 1963), 376

Source: Corporación Nacional de la Vivienda, Memoria del Departamento de Barrios Marginales, 1962 (Lima: CNV, 1962) [unpaginated]

Source: José Matos Mar, Estudio de las barriadas limeñas (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1966), 88

Source: José Matos Mar, Estudio de las barriadas limeñas (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1966), 88

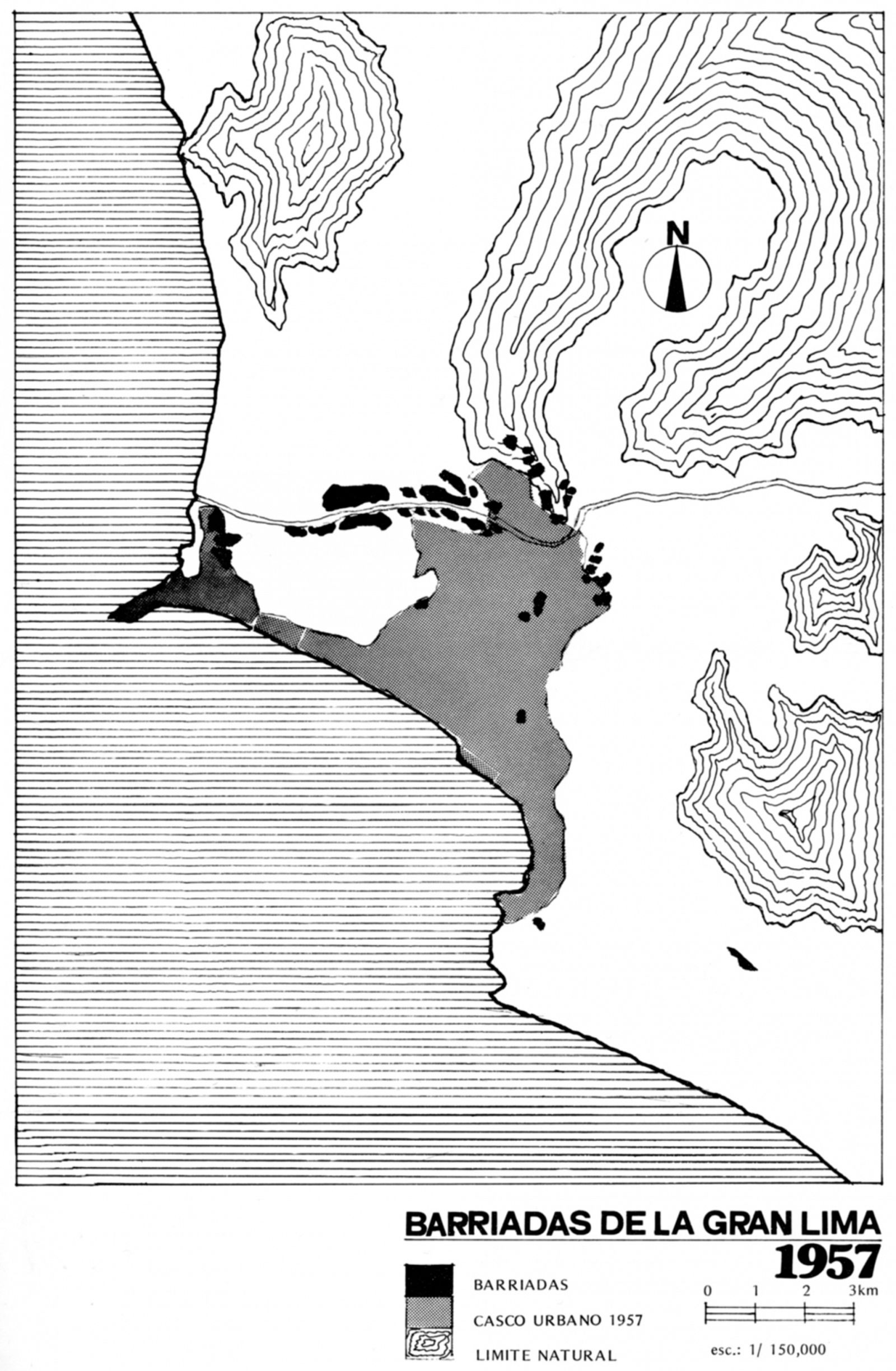

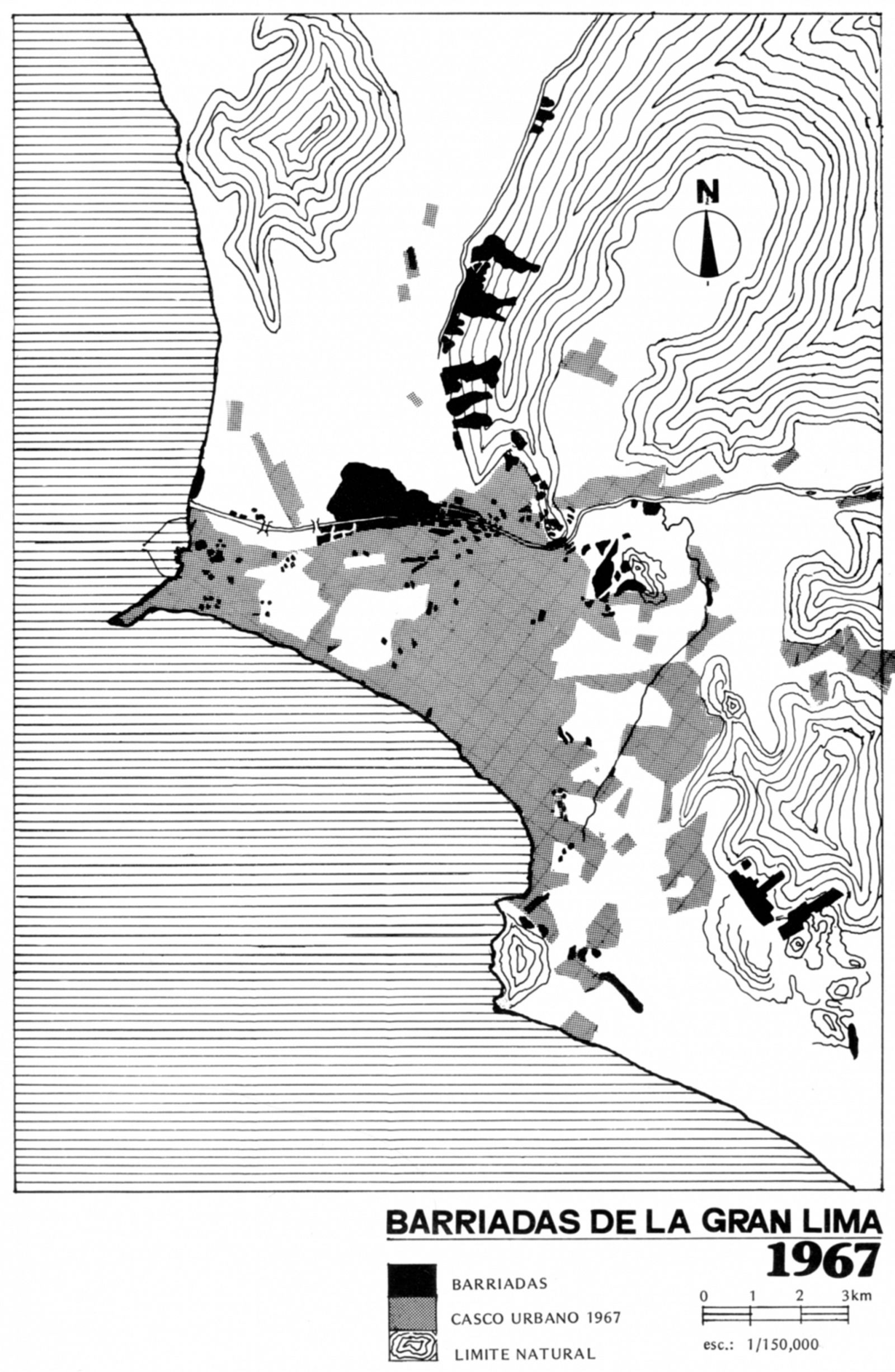

Source: José Matos Mar, Las barriadas de Lima 1957 (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1977), 129

Source: Fondo Nacional de Salud y Bienestar Social, Barriadas de Lima Metropolitana (Lima: FNSBS, 1960), 63

Source: Fondo Nacional de Salud y Bienestar Social, Barriadas de Lima Metropolitana (Lima: FNSBS, 1960), 68

Source: Corporación Nacional de la Vivienda, Memoria del Departamento de Barrios Marginales, 1962 (Lima: CNV, 1962)

Source: Corporación Nacional de la Vivienda, Memoria del Departamento de Barrios Marginales, 1962 (Lima: CNV, 1962)

Source: Instituto Geográfico Militar, 1954

Source: Junta Nacional de la Vivienda, Datos estadisticos de los Barrios Marginales de Lima: Distrito del Rímac (Lima: JNV, 1963)

Source: Junta Nacional de la Vivienda, Datos estadisticos de los Barrios Marginales de Lima: Distrito del Rímac (Lima: JNV, 1963)

Source: Junta Nacional de la Vivienda, Datos estadisticos de los Barrios Marginales de Lima: Distrito del Rímac (Lima: JNV, 1963)

Source: Junta Nacional de la Vivienda, Datos estadisticos de los Barrios Marginales de Lima: Distrito del Rímac (Lima: JNV, 1963)

Source: Corporación Nacional de la Vivienda, Plan Río Rímac: Memoria Descriptiva (Lima: CNV, February 1962)

Source: Ministerio de Vivienda y Construcción, Evaluación técnica y social del programa "Alojamiento H” en la Urbanización Valdiviezo (Lima: MVC, 1981)

Source: Corporación Nacional de la Vivienda, Plan Río Rímac: Remodelación Unidad No. 6 (Lima: CNV, 1962)

Source: Corporación Nacional de la Vivienda, Plan Río Rímac: Remodelación Unidad No. 6 (Lima: CNV, 1962)

Source: John F.C. Turner, ‘Lima Barriadas Today’,in: Architectural Design 33, no 8 (August 1963), 380

Source: Ministerio de Vivienda y Construcción, Evaluación técnica y social del programa "Alojamiento H” en la Urbanización Valdiviezo (Lima: MVC, 1981)

Source: Ministerio de Vivienda y Construcción, Evaluación técnica y social del programa "Alojamiento H” en la Urbanización Valdiviezo (Lima: MVC, 1981)

Source: John F.C. Turner, ‘A New View of the Housing Deficit’, in: David Lewis (ed.), The Growth of Cities, Architects Yearbook – 13 (London: Elek Books, 1971), 123

Source: Ministerio de Vivienda y Construcción, Evaluación técnica y social del programa "Alojamiento H” en la Urbanización Valdiviezo (Lima: MVC, 1981)

Source: Corporación Nacional de la Vivienda, Plan Carabayllo (Lima: CNV, October 1961)

Source: John F.C. Turner, ‘Lima Barriadas Today’,in: Architectural Design 33, no 8 (August 1963), 375

Source: El Arquitecto Peruano, no. 306-308 (January-March 1963)

Source: José Matos Mar, Las barriadas de Lima 1957 (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1977), 9

Source: José Matos Mar, Las barriadas de Lima 1957 (Lima: Instituto de Estudios Peruanos, 1977), 10

- 1 Plan Río Rímac and Unidad Vecinal No. 6

- 2 UPIS: Hacienda Conde Villa Señor, Valdiviezo and Caja de Agua

- 3 Plan Carabayllo

-

1Oficina Nacional de Planeamiento y Urbanismo, Lima: Plan Piloto (Lima: ONPU, April 1949). The plan was produced under the direction of Luis Dorich, the first Peruvian architect to formally study urban planning, completing his studies at MIT in 1944. Josep Lluís Sert and Paul Lester Wiener’s unrealized project for a new civic centre for Lima was one component of the Plan Piloto.

-

2ONPU, Lima Metropolitana: Algunos aspectos de su expediente urbano y soluciones parciales y varias (Lima: ONPU, December 1954), 5, 8.

-

3Ley de Remodelación, Saneamiento y Legalización de los barrios marginales (Lima: Corporación Nacional de la Vivienda, February 1961), 8.

-

4Fondo Nacional de Salud y Bienestar Social, La asistencia técnica a la vivienda y el problema de barriadas marginales (Lima: FNSBS, 13 November 1958), 8.

-

5Ibid., 10, 11.

-

6‘Reglamento de la Ley No. 13517’ (21 July 1961), in: Lima: Historia y urbanismo en cifras (Lima: Ministerio de Vivienda, Construcción y Saneamiento, 2004), 436.

-

7Comisión para la Reforma Agraria y la Vivienda, Informe sobre la vivienda en el Perú (Lima: CRAV, 1958), 307.

-

8FNSBS, La asistencia técnica, op. cit. (note 4), 51.

-

9Wiley Ludeña Urquizo, ‘Fernando Belaúnde Terry o los inicios del urbanismo moderno en el Perú’, in: Tres buenos tigres: vanguardia y urbanismo en el Perú del siglo XX (Huancayo; Lima: Ur[b

-

10Corporación Nacional de Vivienda, Información básica sobre barrios marginales en la república del Perú (Lima: CNV, 1962), 212.

-

11Junta Nacional de la Vivienda, Datos estadisticos de los Barrios Marginales de Lima: Distrito del Rímac, Vol. 1 (Lima: JNV, December 1963), 22, 37, 99, 114.

-

12CNV, Plan Río Rímac: Memoria Descriptiva (Lima: CNV, February 1962), 5.

-

13Ibid., 12.

-

14CNV, Plan Río Rímac – Remodelación de la Zona 6 (Lima: CNV, September 1962).

-

15CNV, Plan Río Rímac – Anteproyecto de Urbanización Popular de la Hacienda Conde Villa Señor: Memoria Descriptiva (Lima: CNV, December 1961).

-

16Ministerio de Vivienda, Evaluación técnica y social del programa ‘Alojamiento H’ en la Urbanización Valdiviezo (Lima: Ministerio de Vivienda, 1980-1981).

-

17Ibid.

-

18Ibid.

-

19John F. C. Turner, ‘Minimal Government- Aided Settlements: Valdivieso and Condevilla Señor Barriadas, Lima, Peru,’ Architectural Design, vol. 33 (1963) no. 8, 379.

-

20Ministerio de Vivienda, Evaluación de un proyecto de vivienda: Evaluación integral del proyecto de vivienda Caja de Agua-Chacarilla de Otero (Lima: Ministerio de Vivienda, 1970), 49.

-

21Ibid., 162.

-

22John F. C. Turner, ‘Lima Barriadas Today,’ Architectural Design, vol. 33 (1963) no. 8, 375.

-

23John F. C. Turner, ‘Barriada Integration and Development: A Government Program in San Martín, Lima,’ Architectural Design, vol. 33 (1963) no. 8, 377.

-

24Turner, ‘Minimal Government-Aided Settlements’, op. cit. (note 19), 379.