- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- mid-rise

- new town

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- Romy Bijl

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijn

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Yasmine Garti

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Michel Kalt

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

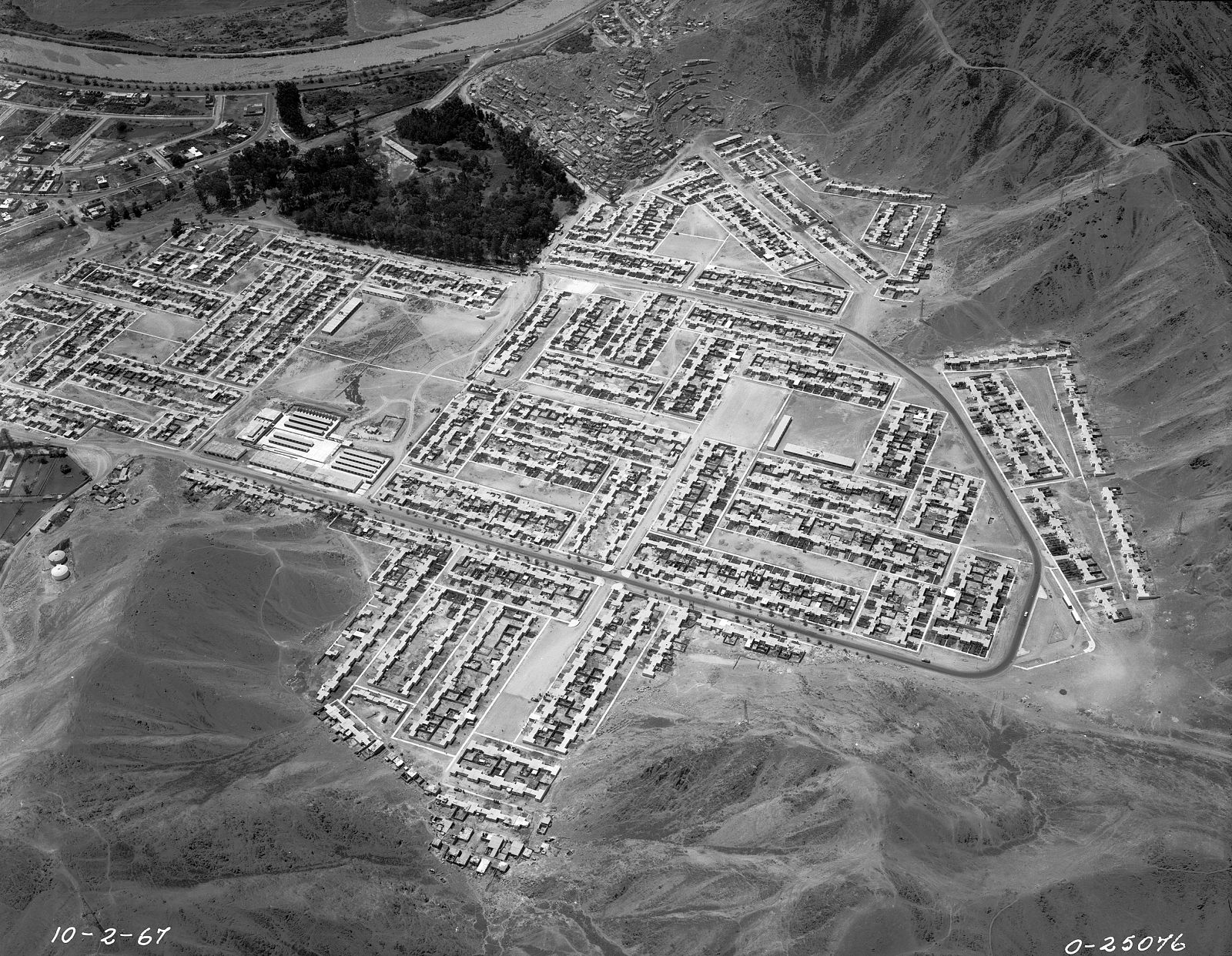

Urbanización Caja de Agua

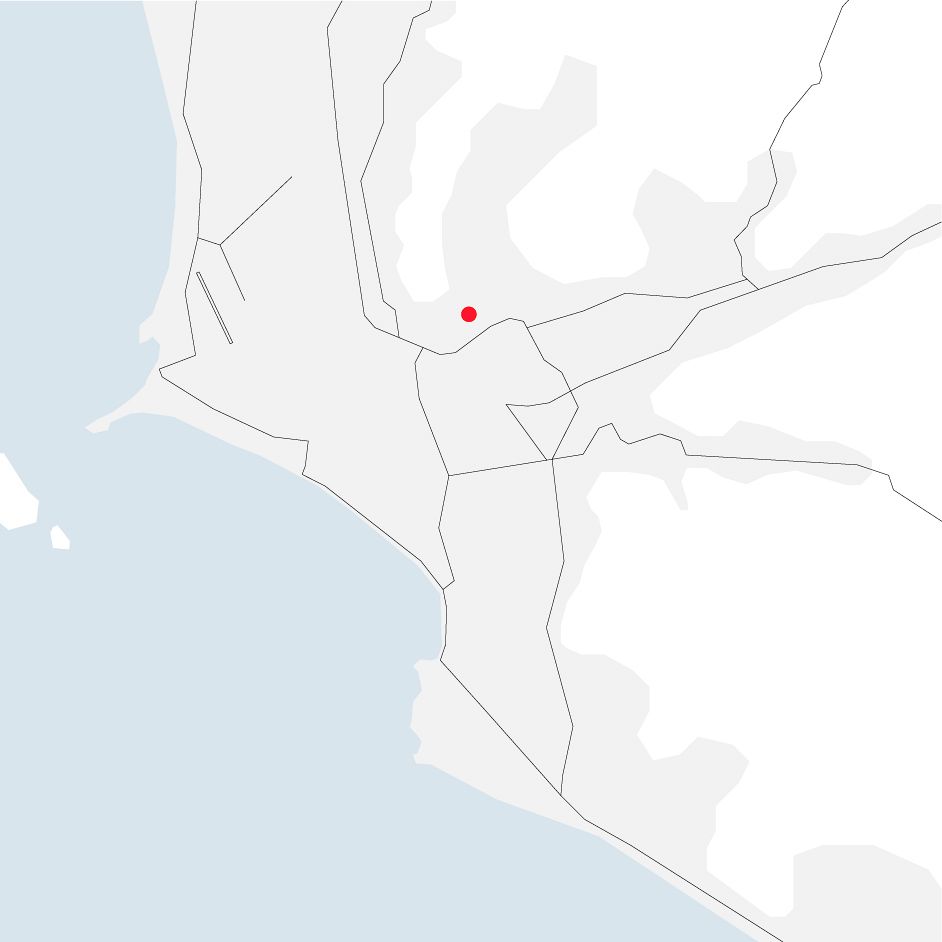

The Caja de Agua development was initially proposed by the Peruvian state housing agency in 1961, as part of its programme to create a new kind of housing project: the Urbanización Popular de Interés Social (UPIS, or Low-Income Social Housing Subdivision). The UPIS offered organized urban development to a minimum standard, substantially below previous government-sponsored housing projects, in an effort to accommodate low-income residents. The urban layouts were to be prepared by the state housing agency, with a range of basic services, and the residents committed to purchasing a core house that they were expected to complete over time using self-help labour. The design of the dwellings followed the concept of the casa que crece (growing house), first proposed in Peru by architect Santiago Agurto in his entry to a 1954 housing competition, and subsequently implemented on a trial basis in a state-sponsored project at Ciudad de Dios, Lima, in 1957. Such projects borrowed and systematized the techniques of barriada (squatter settlement) housing – progressive development, resident participation in construction – but aimed to circumvent ad hoc building through technical assistance and carefully conceived expansion plans.

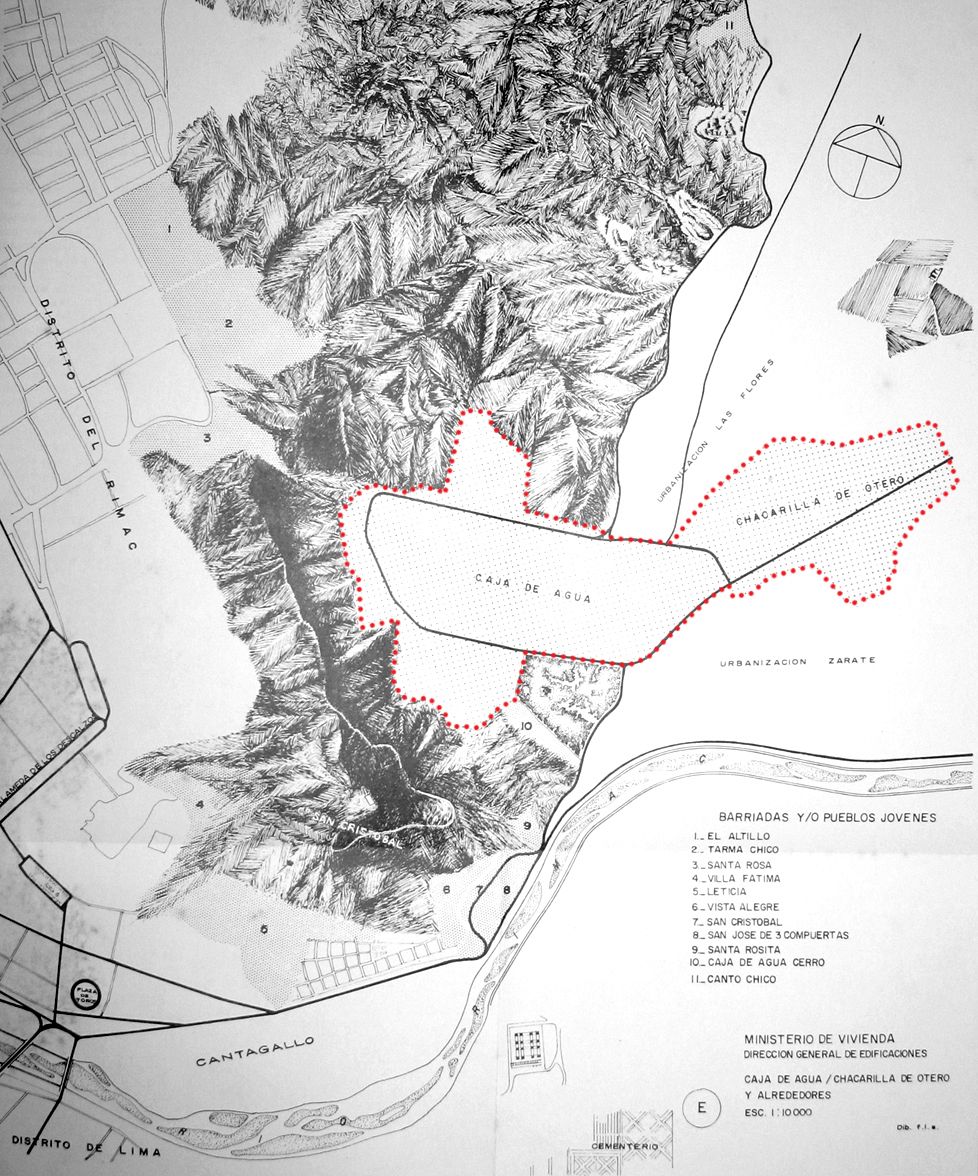

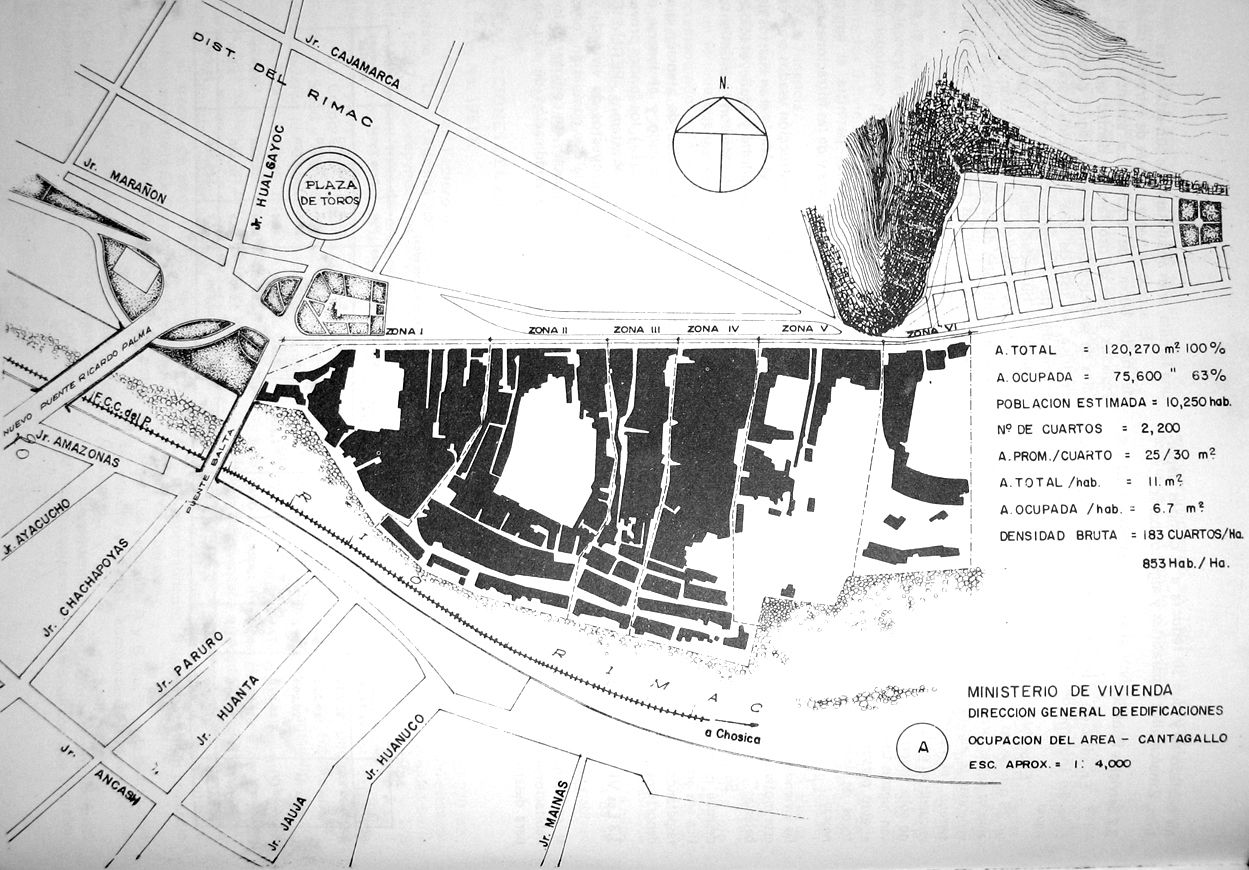

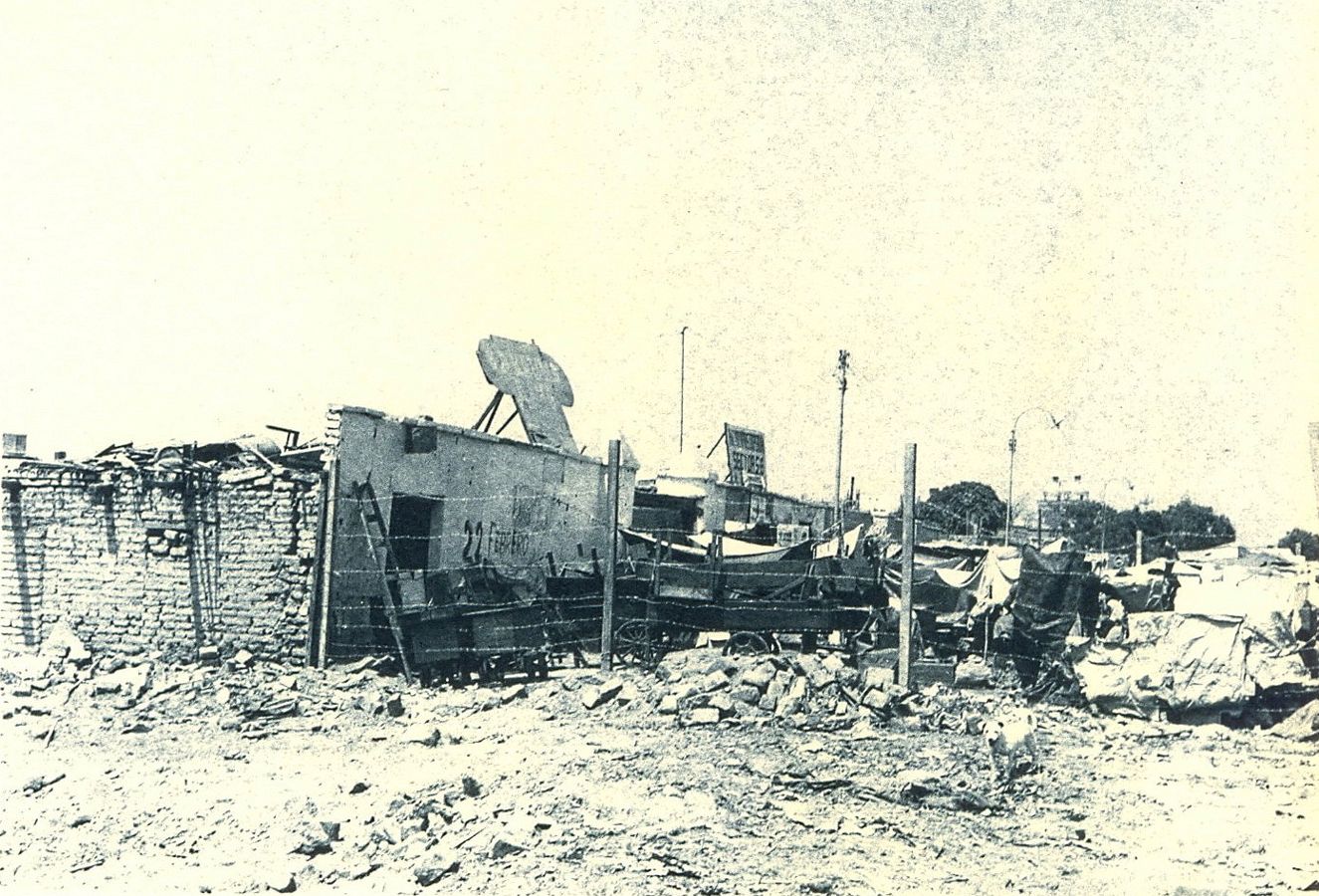

Delays due to administrative and funding issues postponed the implementation of Caja de Agua until 1965, at which time it was decided to supplement the project’s 1,596 lots with several hundred additional lots on a neighbouring site, Chacarilla de Otero. Together these two projects were intended to rehouse residents from Cantagallo, a barriada housing over 2,000 families that had arisen on a private estate bordering the Río Rímac in the centre of Lima. Cantagallo was overcowded, with an average density of 890 people per hectare living in improvised low-rise housing, and its communal facilities were limited to two sports fields, two small markets and a number of bars. Due to its proximity to the city centre, multifamily housing was deemed more appropriate for this valuable site (although this was never built; the site now houses government facilities).

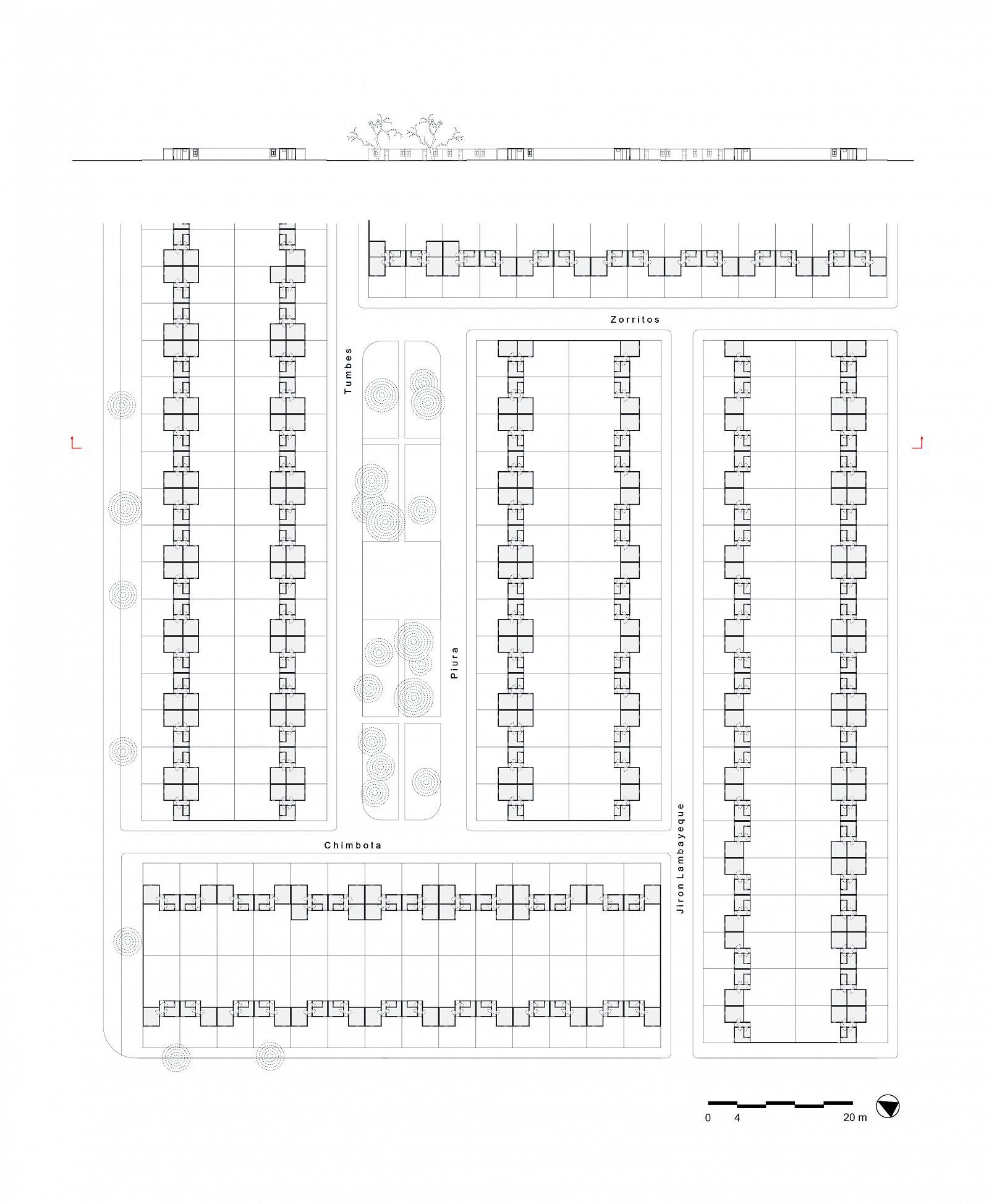

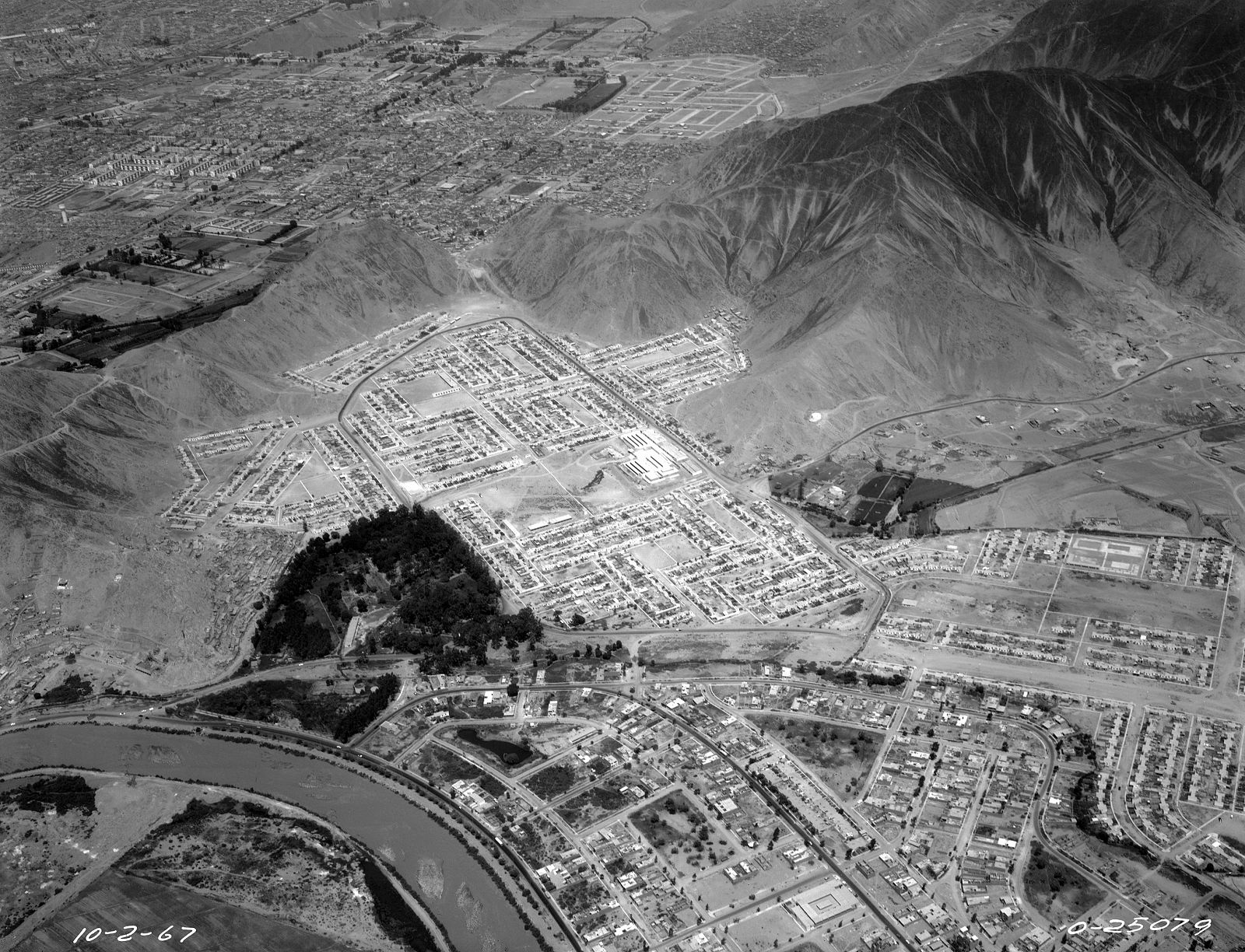

The new plan envisaged much lower density, at 124 people per hectare, and provided for a large number of amenities, including parks, schools, a health post, market, sporting facilities and churches. The housing, built on 8 x 20-m lots, was arranged in blocks of 18 to 24 units, organized to frame a series of open spaces, where the parks, schools and other amenities would eventually be built. However, the plan only indicated the location of these services without guaranteeing their actual execution, which was often left to residents and various public and private entities; as a result, a report on the two settlements after five years of occupancy reported that only a few had been completed.

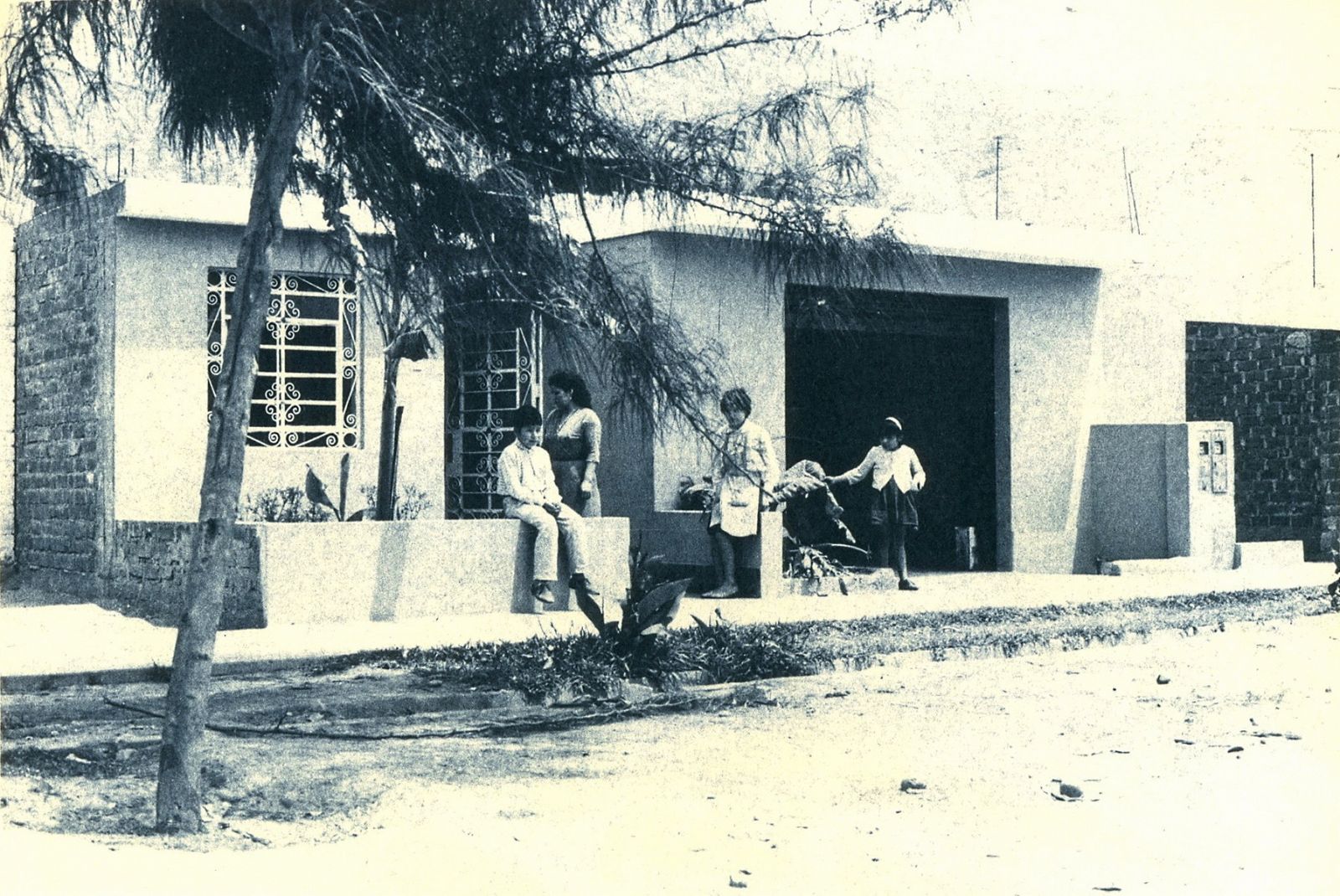

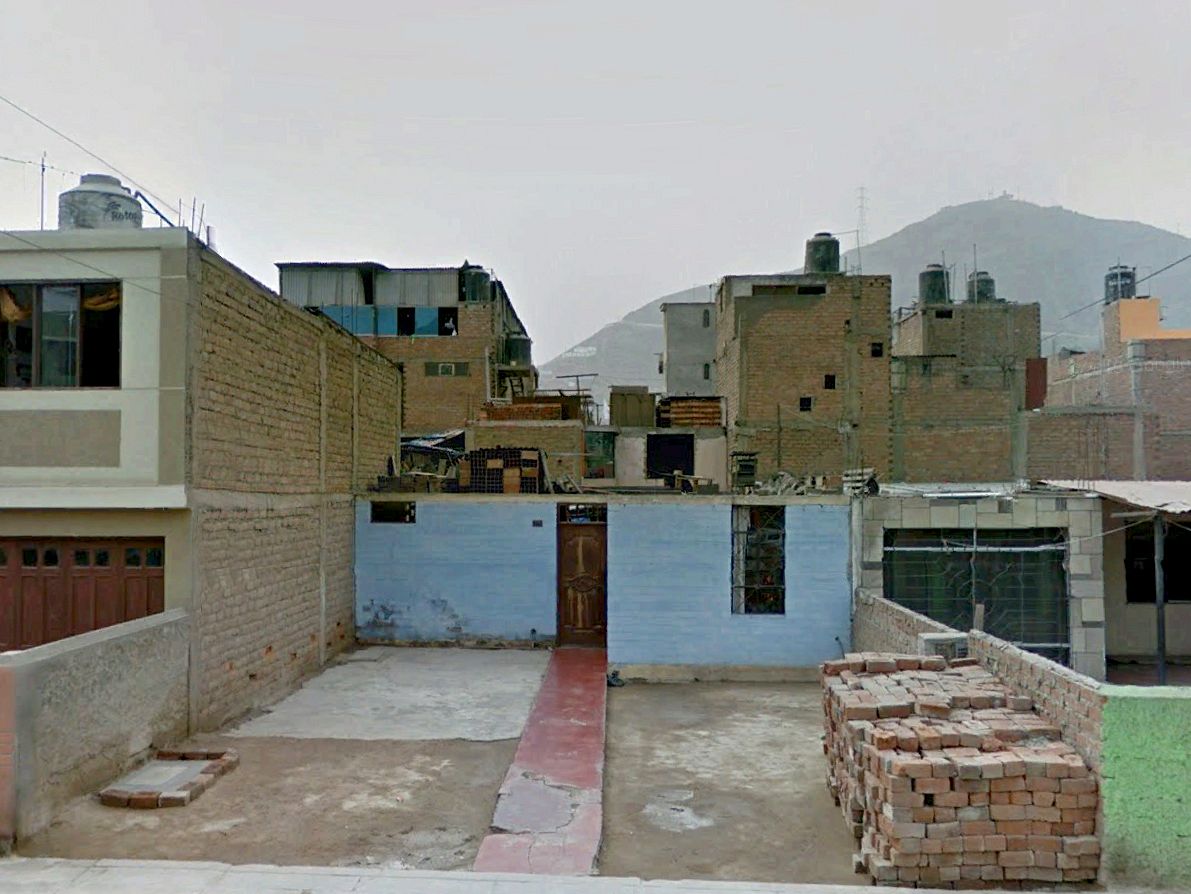

At Caja de Agua, residents were offered the choice of two basic, one-storey houses: Núcleo 1 (31.5 m2) including a functional core (with bathroom and kitchen) and a single multipurpose room; Núcleo 2 (43.75 m2) added to this a second, slightly smaller room. The houses were built in a continuous strip, with the projecting and receding volumes of the façades forming an animated streetscape. The built structure occupied the centre of the lot, leaving around 5 m between the front of the house and the property line, and a slightly larger area at the back of the lot. The construction aimed for maximum economy, with simple materials (such as concrete blocks) that were for the most part left unfinished.

The housing agency prepared a recommended plan for the completed house – foreseeing a living-dining room adjacent to the kitchen, a front garden, a garden patio and two additional bedrooms at the rear. However, in the absence of technical assistance, residents developed their own solutions for the expansion of the house. The post-occupancy report noted that within five years, 94 per cent of residents had begun to make additions, the majority adding between four and six rooms; in part this was achieved by enclosing elements such as the garden patio. Many were subdividing their properties for rental income, raising concerns that the proliferation of subleasing and the ever-increasing density marked the first step towards replicating the environment of Cantagallo. For the authors of the report, this drive to maximize household earnings generated unambiguously negative urban consequences. In conclusion, they observed that the emerging patterns of development at Caja de Agua called for a better balance between individual autonomy in managing the growth of the house and maintaining a certain coherence in the streetscape and the neighbourhood as a whole. Yet in the absence of overarching planning controls, this difficult negotiation was never resolved.

Photo: © Gustavoc

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Photo: © Archivo del Servicio Aerofotografico Nacional de Peru

Photo: © Archivo del Servicio Aerofotografico Nacional de Peru

Photo: © Archivo del Servicio Aerofotografico Nacional de Peru

Photo: © Google Streetview, 2014

Photo: © Google Streetview, 2014

Photo: © Google Streetview, 2014

Photo: © Google Streetview, 2014

Photo: © Google Streetview, 2014

Photo: © Google Streetview, 2014