- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijns

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Marja Elsinga

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Marietta Haffner

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Henk Jonkers

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Chiara Tobia

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Afua Wilcox

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

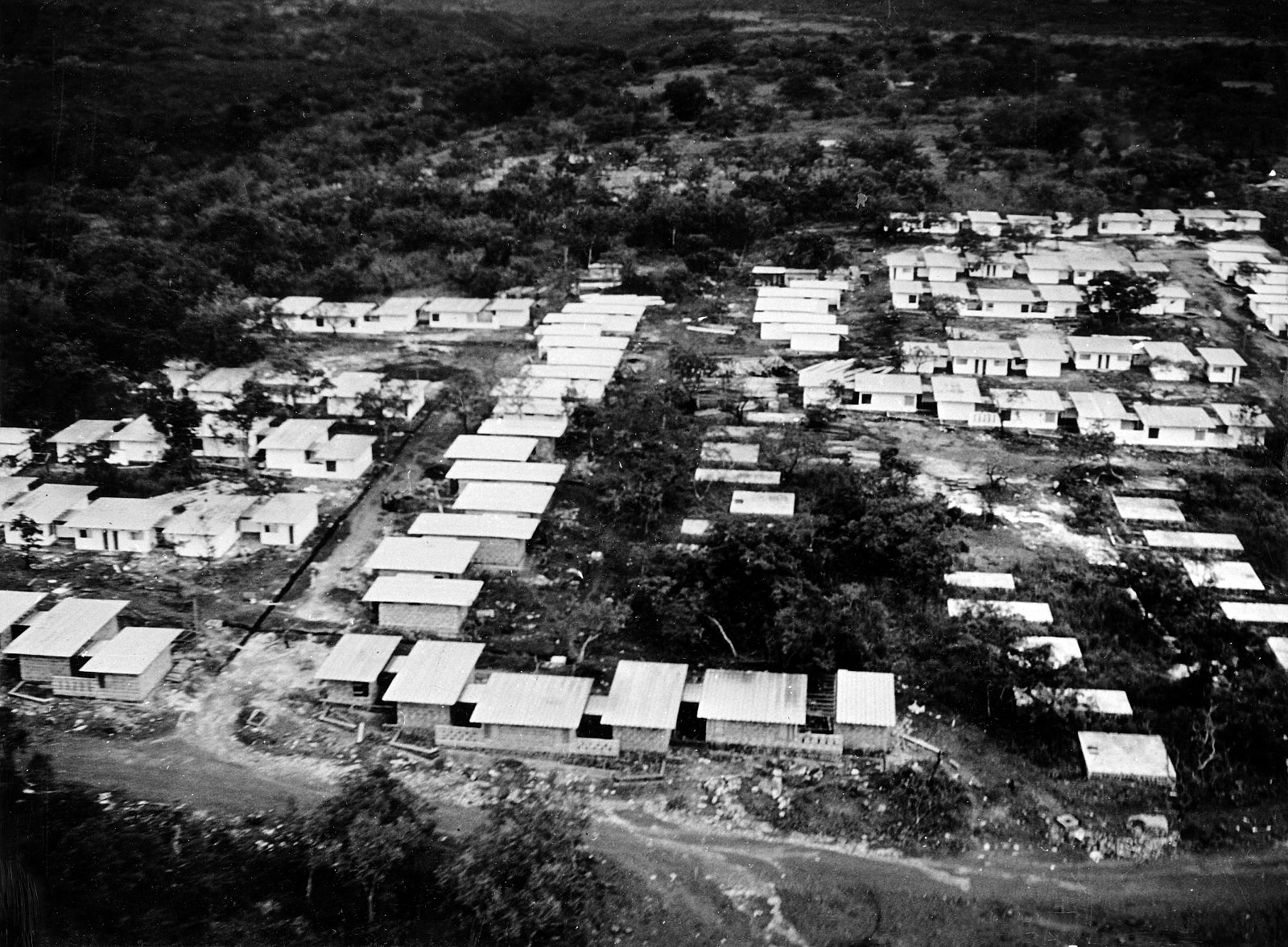

Fria New Town

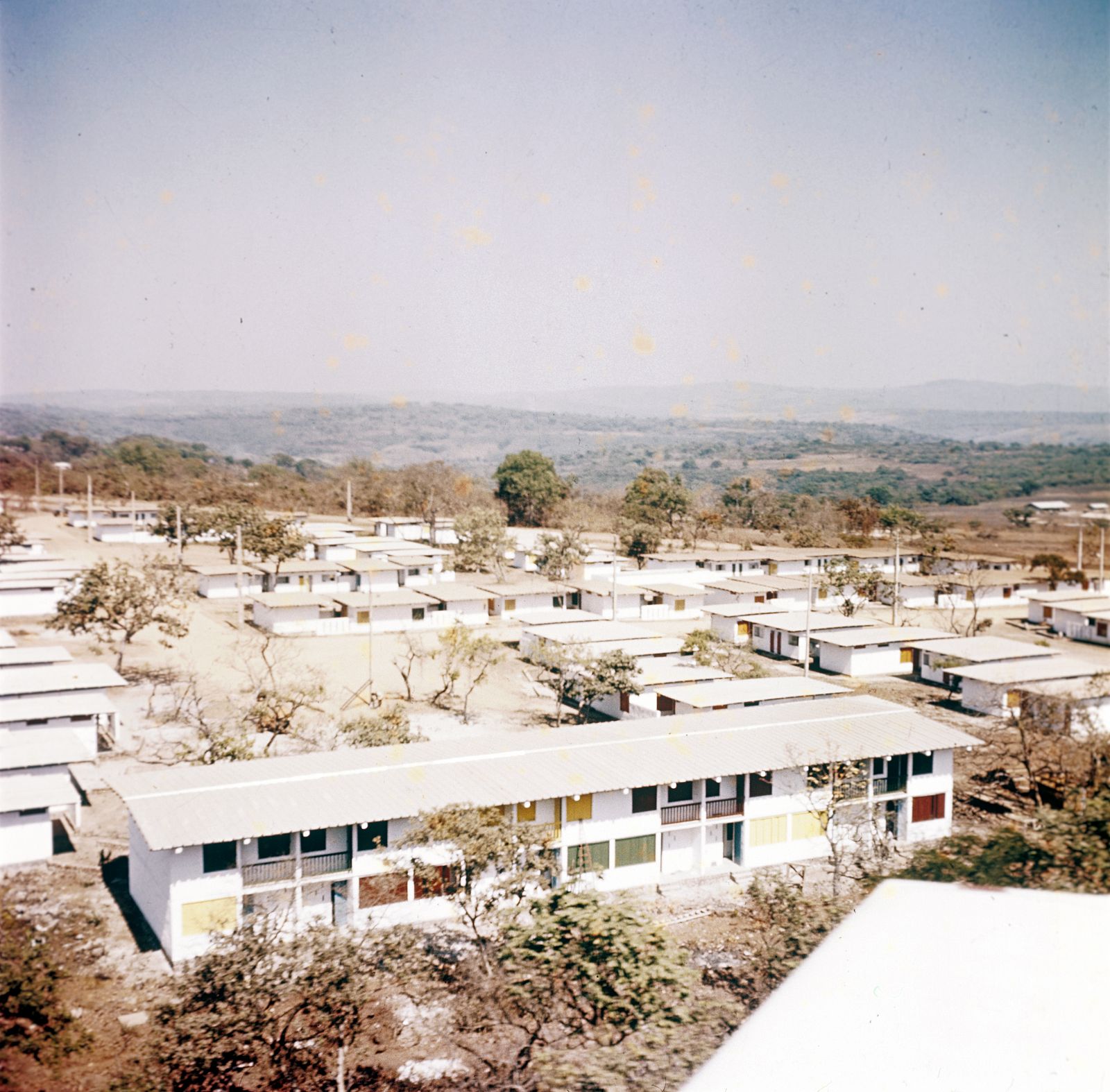

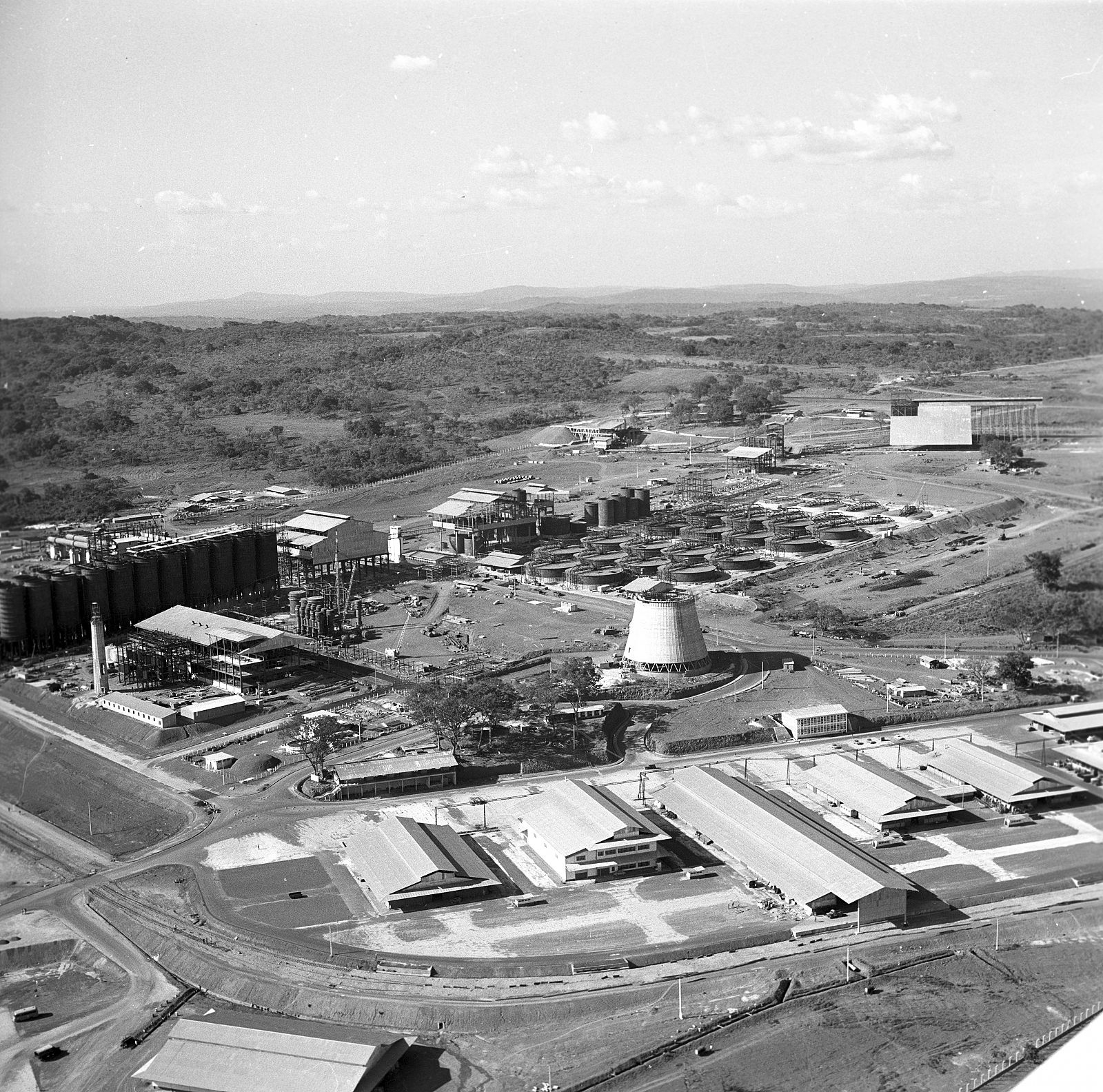

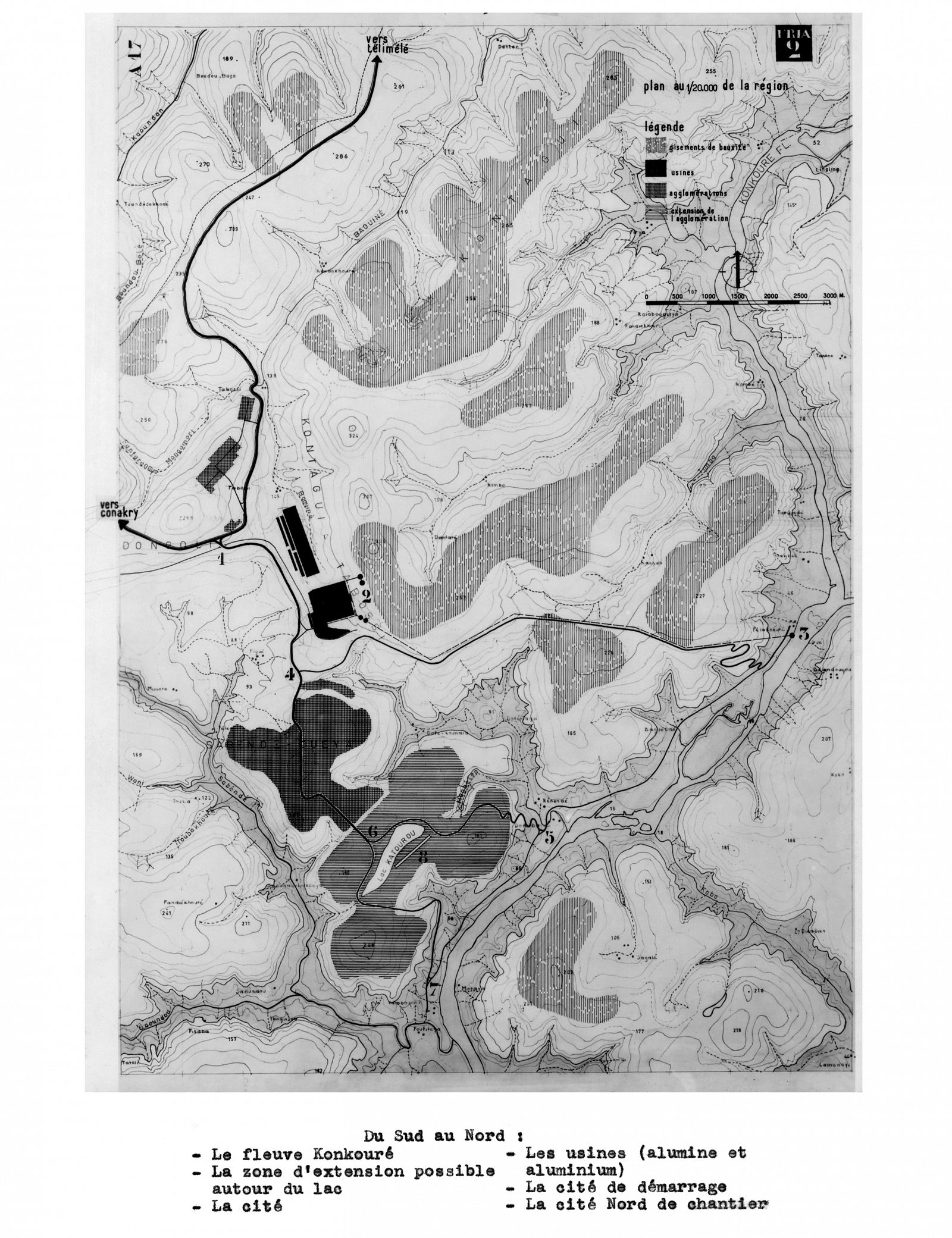

Fria, in Guinea, is a prime example of French late-colonial industrial New Town planning. It was designed and built from scratch between 1956 and 1964 to house both the senior staff and workers of a new bauxite extraction and aluminium production plant owned by the French company Péchiney. The planning and construction of a factory that was projected to produce no less than 15 per cent of the world’s total aluminium stock came, not coincidentally, at the moment when soon-to-be President Ahmed Sékou Touré called upon the Guinean people to vote for total independence, and thus refuse to become part of the Communauté Française. Discursively, Fria was presented as one of the key engines of industrialization and urbanization in Guinea, and as such the locus par excellence of postcolonial social and economic fulfilment. 1 Simultaneously, however, taking responsibility of the planning of Fria and assuming ownership of the aluminium plant allowed France, through Péchiney, to regulate the modernizing process, all the while protecting its economic interests in Africa in view of the imminent secession. This ambiguity, between emancipatory socioeconomic responsibility and control, translates on different levels of Fria’s planning and design.

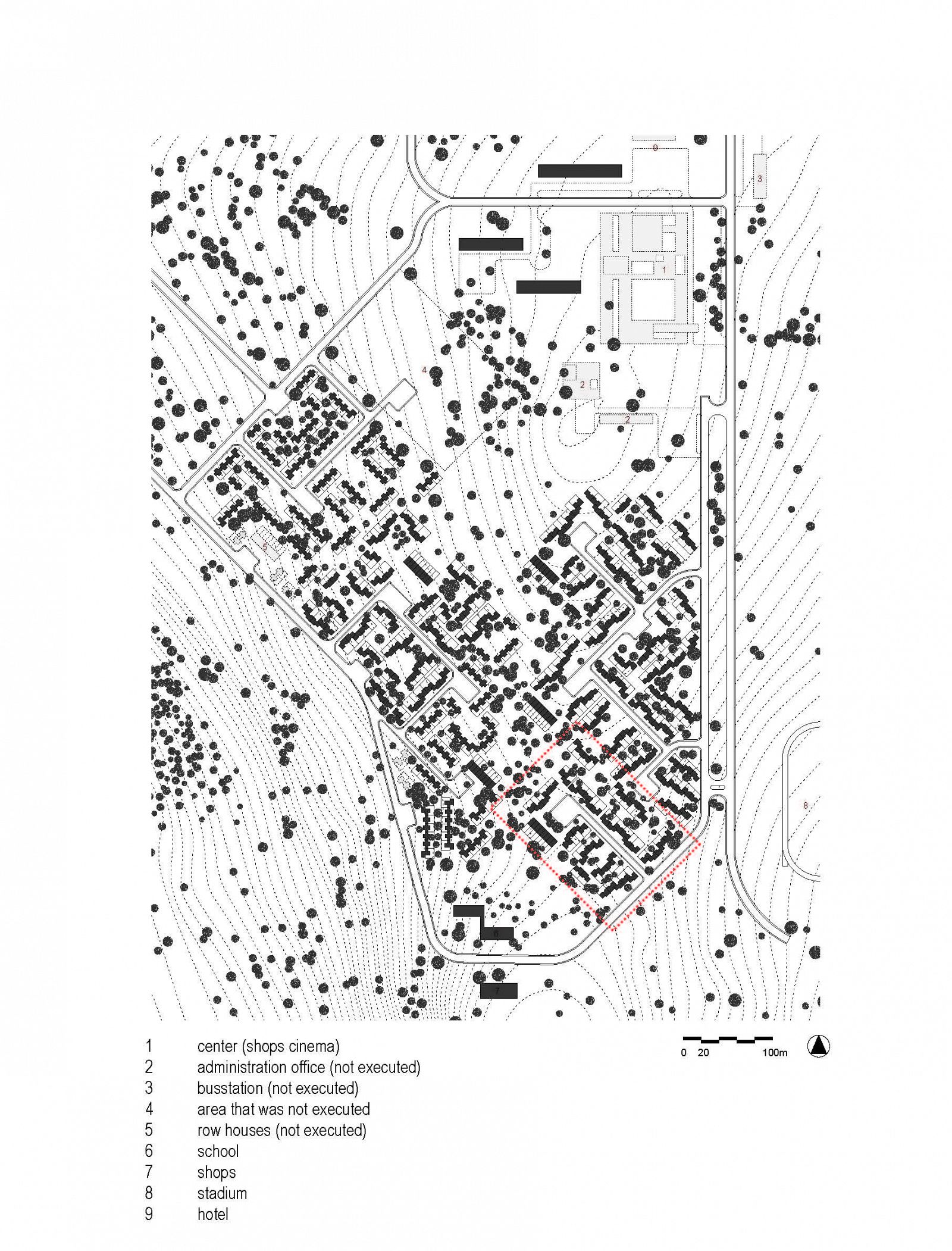

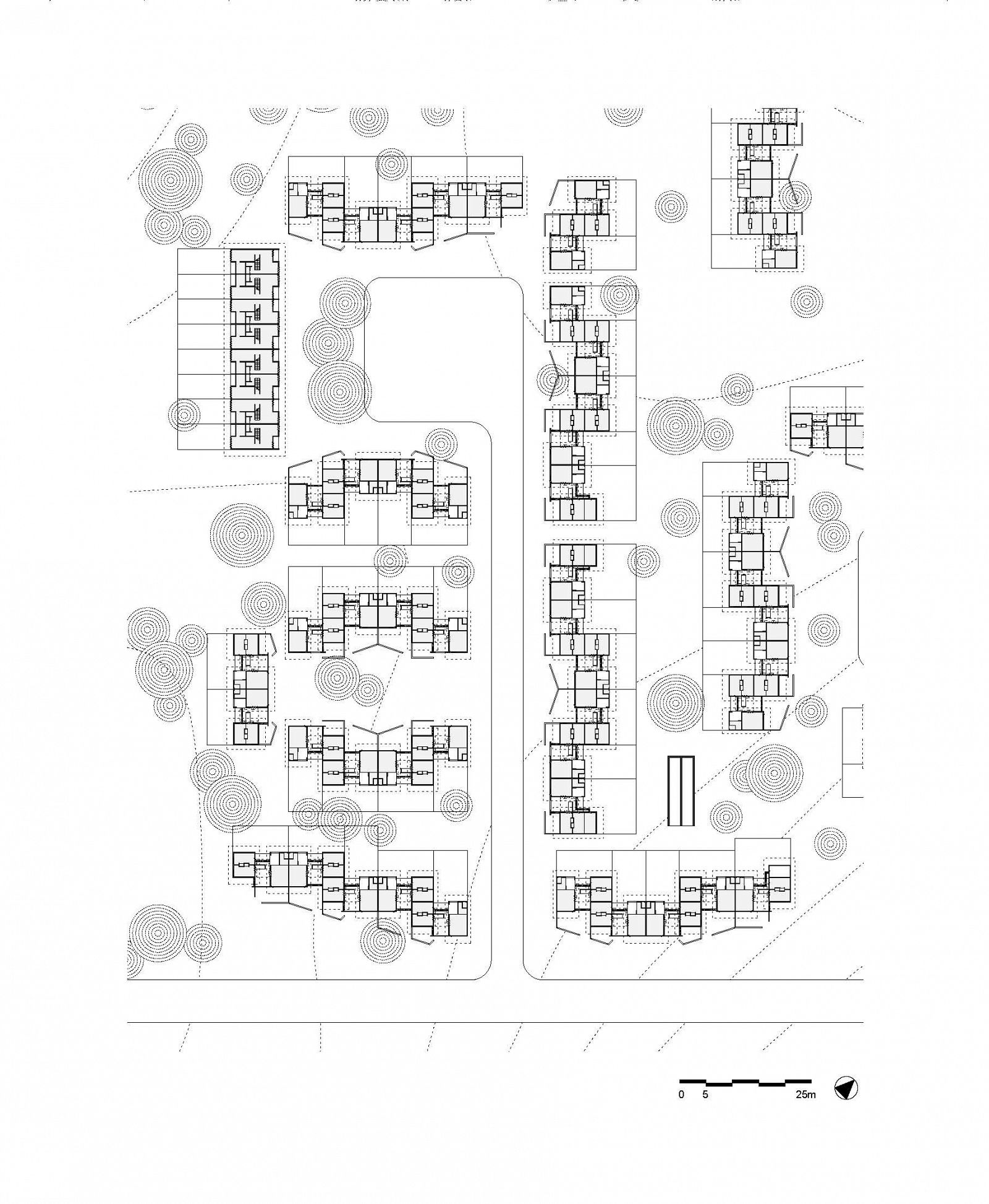

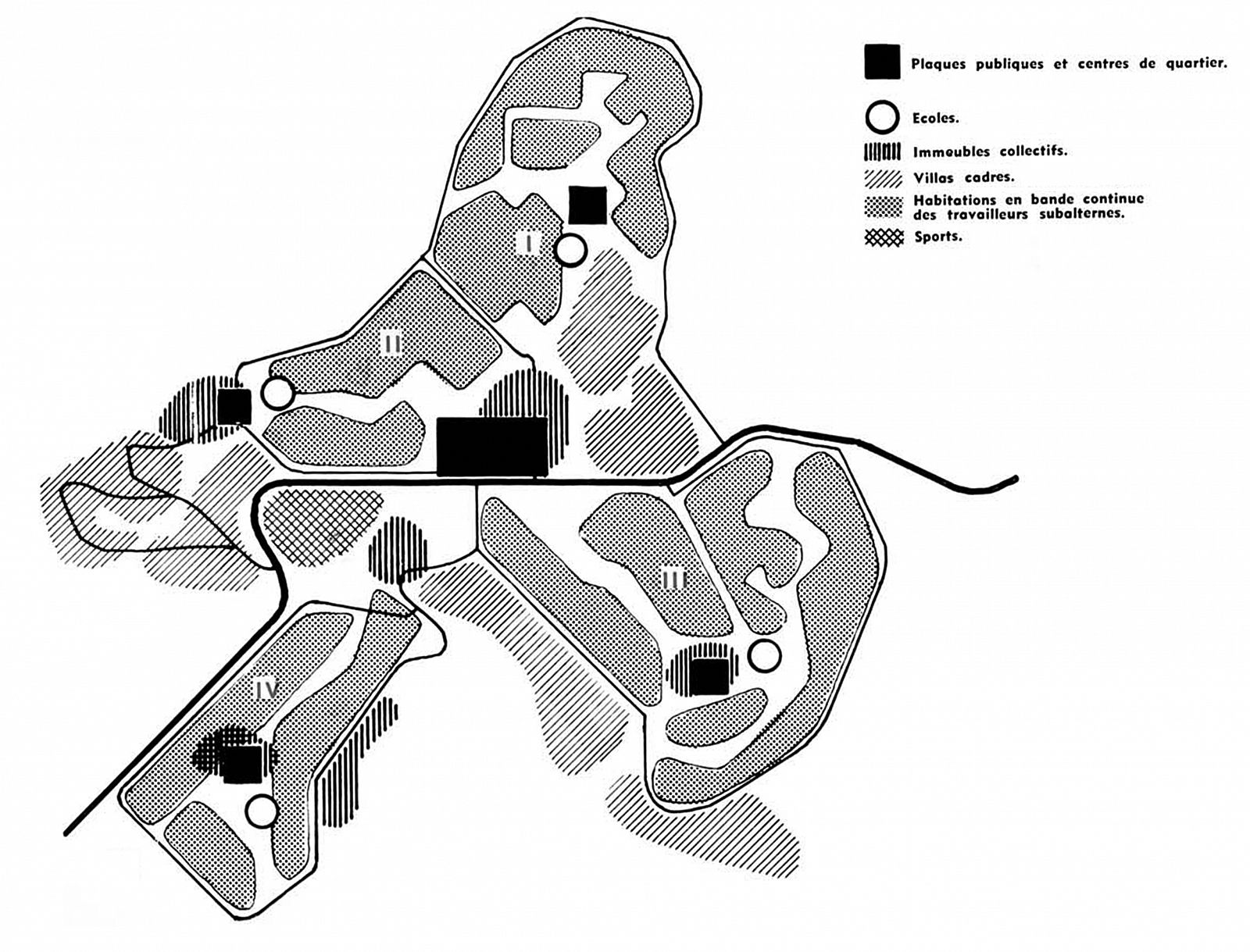

Since the aluminium plant was located 150 km from the nearest city – the capital Conakry – it was essential for the new town to be entirely self-sufficient for its 20,000 projected inhabitants. The master planning of the town was entrusted to famous French planner and architect Michel Écochard. In line with the modernist principles of functional zoning prescribed by the Charter of Athens,2 Fria is located on a plateau at about 1.5 km south of the factory.3 The administrative, commercial and recreational functions are grouped and placed centrally between four distinct housing pockets each providing for about 5,000 dwellers. Circulation is strictly subdivided according to speed and volume.4 Finally, a system of radiating green zones connects the housing units with each other and links them to the town centre, which is marked by three high rise apartment buildings designed by the office of French architects Guy Lagneau, Michel Weill and Jean Dimitrijevic (Atelier LWD).5 The low-rise dwellings for African workers were, in turn, designed by the young architecture collaborative of Michel Kalt, David Pouradier- Duteil and Pierre Vignal (KPDV).

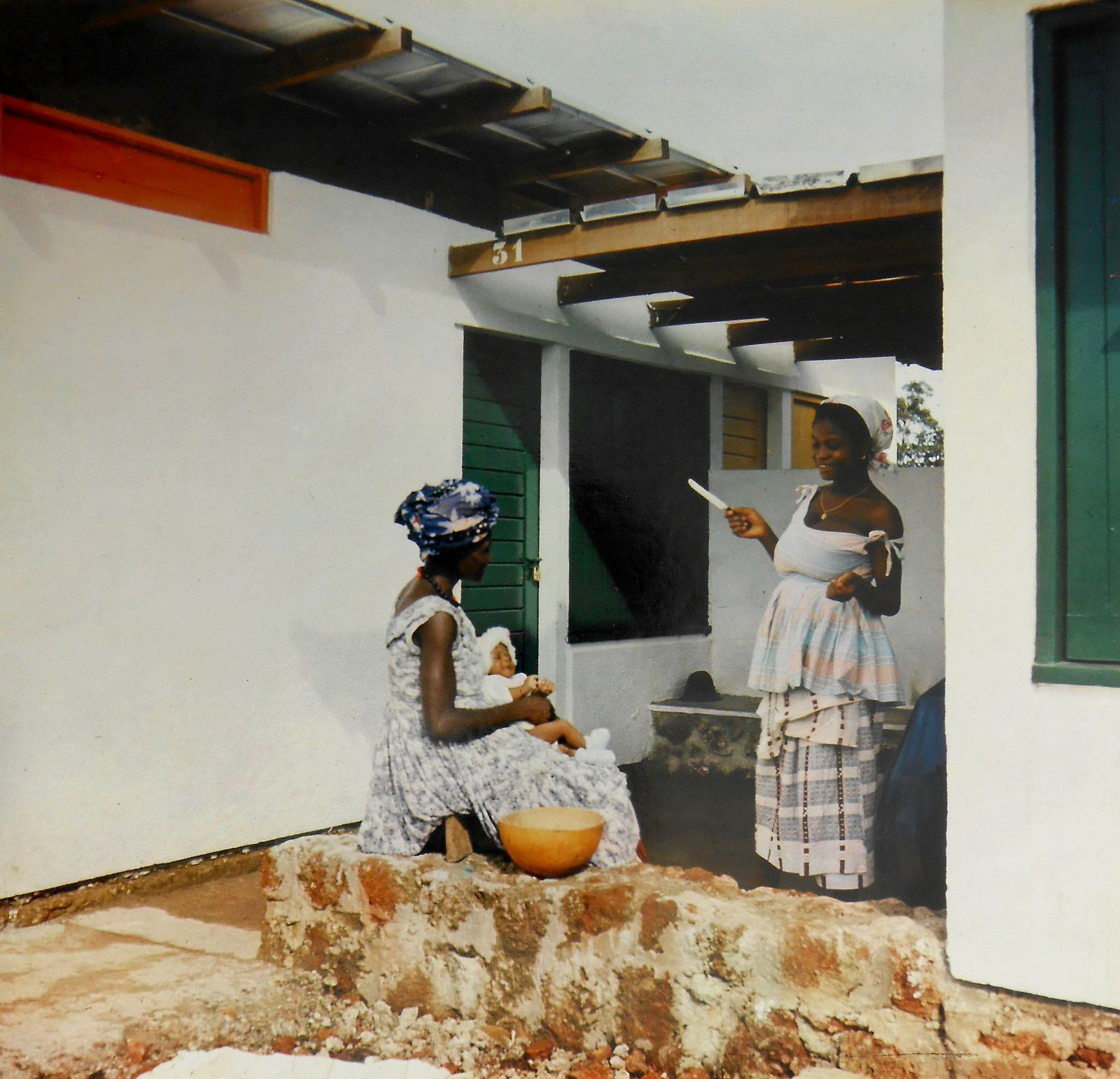

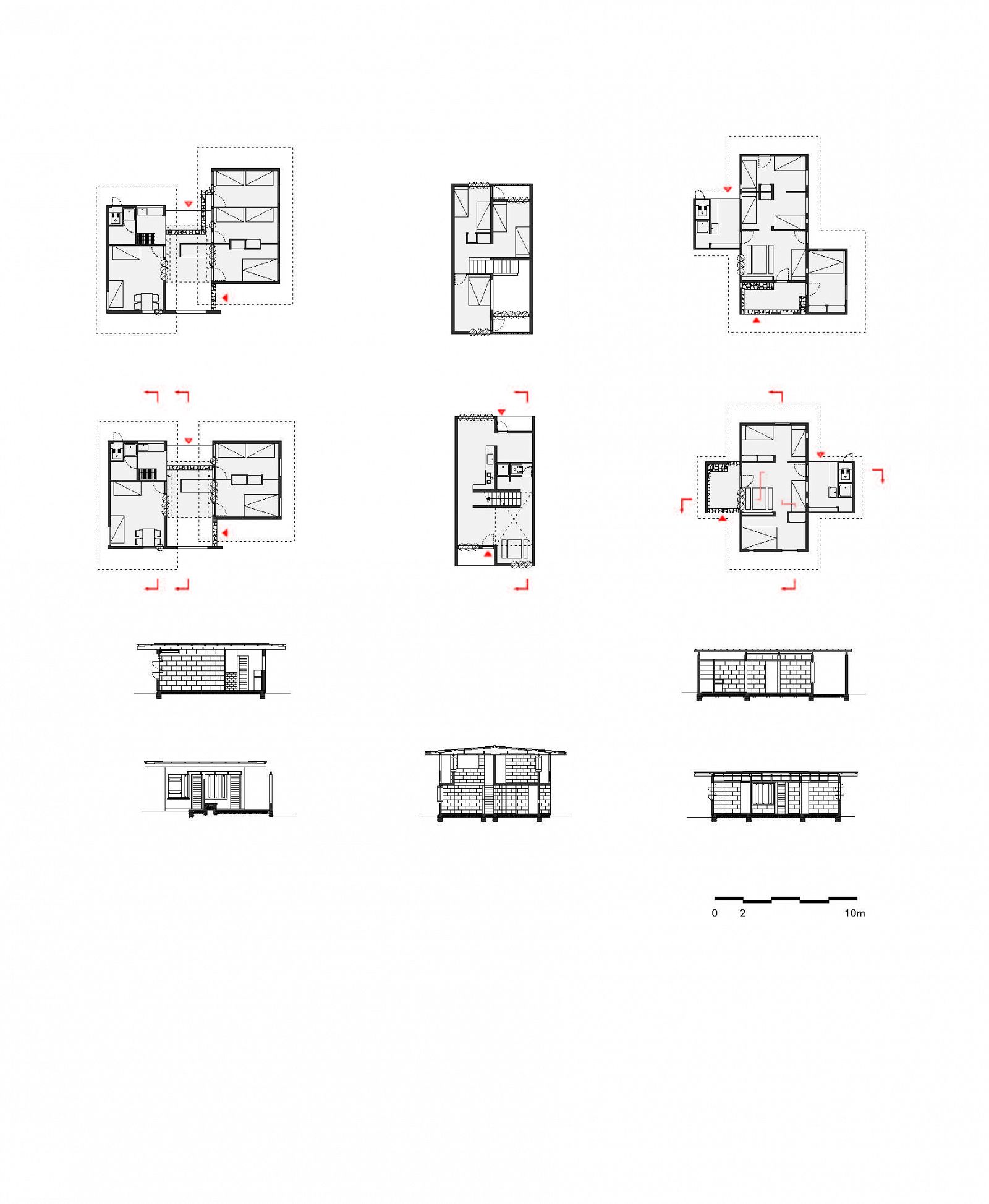

KPDV designed three different plan types for African worker families. Within each housing pocket, the dwellings are organized around a secondary commercial centre and a primary school, and lavishly surrounded by open space and greenery. While a Type B dwelling is designed as a typical Western European terraced house, with living spaces on the ground floor and bedrooms on the first floor, Type A and Type C dwellings are designed so as to mitigate the process of social modernization by providing space for traditional habits and social customs. On one side, they give out onto small public spaces concentrating social and civic life, while on the other side the private gardens open onto green espaces libres where more informal encounters and domestic activities can take place. By thus providing a double orientation to the individual housing unit, male and female living areas are explicitly demarcated. This sensitivity and attention for the local can be traced back to Michel Kalt’s experience as a dissertation student at the Paris Beaux-Arts Academy. In 1949, he undertook a six-month study trip to Cameroon with six fellow students, documenting traditional ways of building and living.6 Besides the double orientation of the houses, the arrangement of rooms around a centrally positioned veranda or living room, for instance, mirror Kalt’s observations of dwelling compounds in northern Cameroon, while the semi-outdoor kitchen opening onto the private garden is inspired by African female customs in the preparation of food.

Both Écochard’s master plan and KPDV’s design of the different dwelling types reflect the ambiguity of the promise of social fulfilment and welfare embedded in the New Town project of Fria. While Écochard’s scheme neatly separates the villas for the senior staff from the workers’ housing by a green zone neutre that is in some ways reminiscent of prewar urban planning in the colonies,7 KPDV’s dwelling designs play their part in a carefully orchestrated mediation between the inhabitant and his environment, modernity and tradition, inhabitants of different social standing, and different ethnic groups. Despite this apparent ambiguity, Fria was a bustling city, a ‘petit-Paris’, until not so very long ago. In 1997, however, Péchiney left the aluminium plant to the Guinean government, leaving Fria behind as ‘une ville désormais asphyxiée, manquant de tout: d’eau, d’électricité, de nourriture et d’espoir’.8

-

1As the main French architecture magazine l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui reported at the time, it was ‘une justice à rendre à une société privée de montrer qu’elle sut promouvoir un urbanisme nettement orienté, dans sa technique contemporaine, vers le point de vue social’. L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, no. 88 (February-March 1960), 96-101.

-

2For Écochard, these African terres vierges formed the ideal context for the full realization of the principles of the Charter of Athens, which could never entirely be applied back in France. See also Tom Avermaete’s work on Écochard as a planner in Morocco, for instance ‘Framing the Afropolis. Écochard and the African City for the Greatest Number’, OASE, no. 82 (2010), 77-100.

-

3Thus, the town would not be hindered by the polluted air emitted by the factory.

-

4This organization of transport infrastructure mirrors Le Corbusier’s 7V road system, which he applied, for instance, in the planning of Chandigarh; see e.g. Tom Avermaete, Maristella Casciato, et al, Casablanca Chandigarh: A Report on Modernization (Montreal: Canadian Center for Architecture/ Zurich: Park Books, 2014); Ernst Scheidegger, Maristella Casciato and Stanislaus von Moos, Chandigarh 1956: Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Jane B. Drew, E. Maxwell Fry (Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2010).

-

5The office was also responsible for the design of the villas of the senior staff, the club and the swimming pool.

-

6This led to the making of an atlas and a film, Cases.

-

7On colonial urban planning, see e.g. Carlos Nunes Silva (ed.), Urban Planning in Sub-Saharan Africa: Colonial and Post-Colonial Planning Cultures (New York: Routledge, 2015).

-

8‘since then a suffocating city, with a shortage of everything: water, electricity, food and hope’. http://economie.jeuneafrique.com/regions/afriquesubsaharienne/ 21422-guinee-le-cauchemar-de-fria.html. Accessed 20 April 2015.

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

© Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Michel Écochard Archive

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Michel Écochard

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

© Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Michel Écochard Archive

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

© Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Michel Écochard Archive

© Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Michel Écochard Archive

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Michel Écochard

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Michel Écochard

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Michel Écochard

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Michel Écochard

Photo: © Aga Kahn Trust for Culture | Michel Écochard

-

1As the main French architecture magazine l’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui reported at the time, it was ‘une justice à rendre à une société privée de montrer qu’elle sut promouvoir un urbanisme nettement orienté, dans sa technique contemporaine, vers le point de vue social’. L’Architecture d’Aujourd’hui, no. 88 (February-March 1960), 96-101.

-

2For Écochard, these African terres vierges formed the ideal context for the full realization of the principles of the Charter of Athens, which could never entirely be applied back in France. See also Tom Avermaete’s work on Écochard as a planner in Morocco, for instance ‘Framing the Afropolis. Écochard and the African City for the Greatest Number’, OASE, no. 82 (2010), 77-100.

-

3Thus, the town would not be hindered by the polluted air emitted by the factory.

-

4This organization of transport infrastructure mirrors Le Corbusier’s 7V road system, which he applied, for instance, in the planning of Chandigarh; see e.g. Tom Avermaete, Maristella Casciato, et al, Casablanca Chandigarh: A Report on Modernization (Montreal: Canadian Center for Architecture/ Zurich: Park Books, 2014); Ernst Scheidegger, Maristella Casciato and Stanislaus von Moos, Chandigarh 1956: Le Corbusier, Pierre Jeanneret, Jane B. Drew, E. Maxwell Fry (Zurich: Scheidegger & Spiess, 2010).

-

5The office was also responsible for the design of the villas of the senior staff, the club and the swimming pool.

-

6This led to the making of an atlas and a film, Cases.

-

7On colonial urban planning, see e.g. Carlos Nunes Silva (ed.), Urban Planning in Sub-Saharan Africa: Colonial and Post-Colonial Planning Cultures (New York: Routledge, 2015).

-

8‘since then a suffocating city, with a shortage of everything: water, electricity, food and hope’. http://economie.jeuneafrique.com/regions/afriquesubsaharienne/ 21422-guinee-le-cauchemar-de-fria.html. Accessed 20 April 2015.