- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijn

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

Affordable Housing as Development Aid

Michel Écochard: New Roles, Methods and Tools of the Transnational Architect

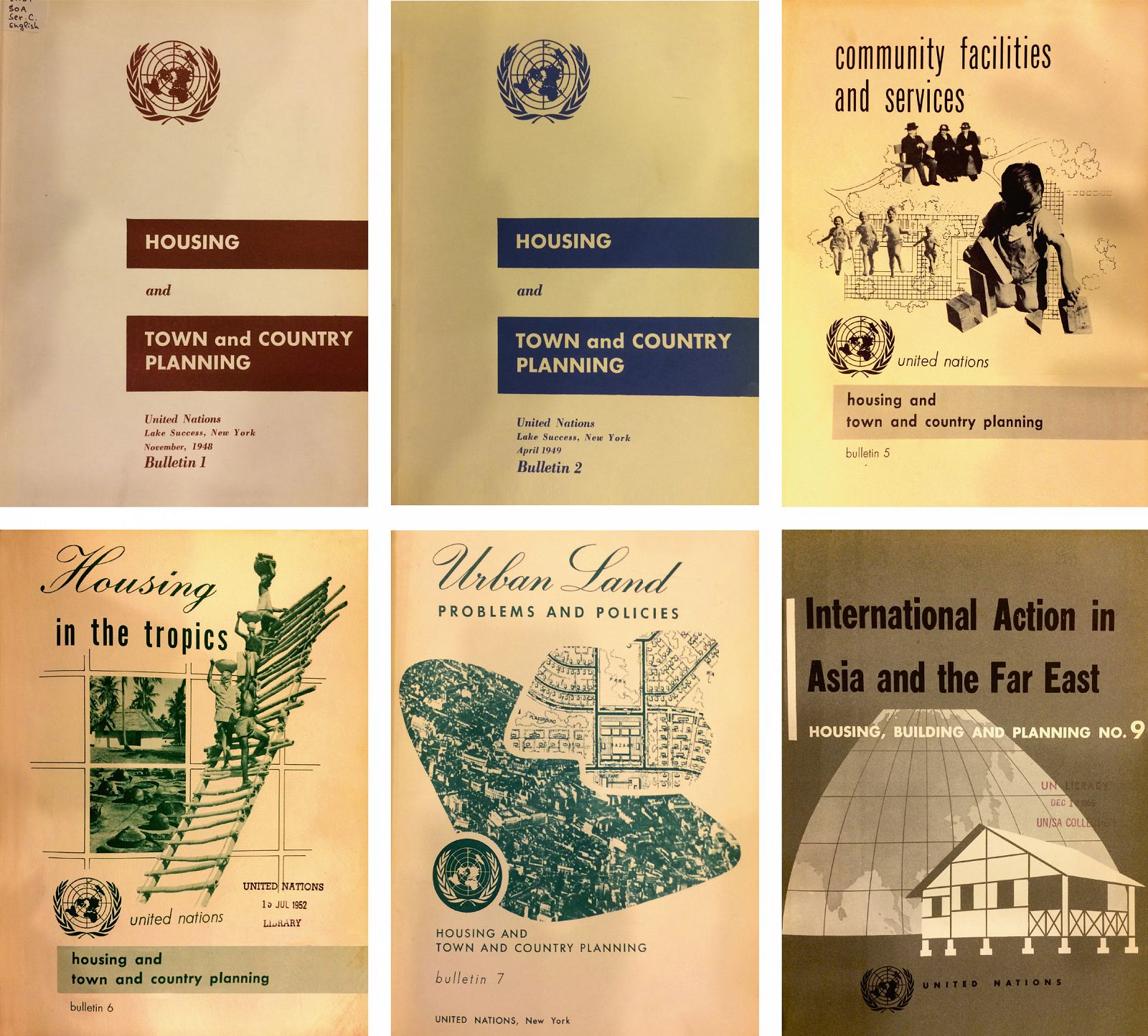

It was not by coincidence that the UN Economical and Social Council decided in 1948, only a few years after the actual foundation of the United Nations as an organization, to start a division on Housing and Town and Country Planning.1 This division was a central component in the larger so-called technical assistance programme that the United Nations developed to help countries that were in need – ranging from war-affected countries in Europe to newly independent nation-states in African and Asia. Among the members of the council, there was a clear understanding that affordable housing was a universal human right, as well as a main matter of concern and a prime field of intervention for the new international organization.2

United Nations Urbanism

The Housing and Town and Country Planning (HTCP) division was from its inception until 1966 headed by a former member of the Congress Internationaux d’Architecture Moderne (CIAM), the Yugoslavian Ernest Weismann.3 The new division was defined first and foremost as a base of expertise: it was meant to gather worldwide knowledge on the matter of affordable housing that was generated in the different member countries. With this in mind, the HTCP managed to unite different professional camps of architects and urban planners, gathering public administrations and avant-garde groups, but also organizations that had previously been keen to establish an ideological distance such as the CIAM and the International Union of Architects (IUA).4

The knowledge that was gathered was made available to the member countries in different ways: through the publication of manuals and a bulletin, through the installation of a library and by curating a mediatheque with movies on different forms of housing worldwide.5 Besides this function as a base of expertise, the HTCP section also focussed on more concrete sorts of intervention. It would commission urban and regional planners, architects, engineers and technicians to go on missions to regions, countries or cities that were in need. In the decades after 1948 the HTCP would initiate hundreds of missions, organize trainings, make regional and urban plans and even design buildings for a variety of contexts and places. The numerous urban plans, neighbourhoods and buildings that resulted from these ‘development aid’ initiatives have for a long time been the no-go zones of architectural criticism and historiography.6 Plans and projects have often been considered as too instrumental and too technical in character to carry any cultural significance.

This article suggests that the new condition of ‘architecture as development aid’, driven by the United Nations but also by many other private and governmental organizations, engendered a series of crucial changes. First, it required that architects and urban planners adjust their approaches, tools and roles for working across nations and across cultures. They had to develop methods of analysis and intervention that could be rapidly spread across the world and different cultural, social and political conditions. Second, the fact that architects and urban planners were working under the regimes of ‘development aid’, sometimes also coined as ‘aided self-help’ or ‘technical assistance’, required that they had to reflect on the character of their own agency in relation to that of others. The very notion of ‘aid’ put into question the role of the expert-architect, as well as the function of his expertise, vis-à-vis other actors and other knowledge of the built environment. Third, within the urban and architectural projects of architects and urban planners working as development aid experts, new notions of ‘affordable housing’ emerged. While in the official discourses of development aid affordability was mainly understood as economic accessibility, in the proposals of architects and urban planners other perspectives of affordability emerged.

French urban planner, architect and archaeologist Michel Écochard was one of the key players in this new regime of development aid. Écochard’s career seems to be inextricably tied to the large geopolitical changes of the post-war period: he started in the socially charged territories of the French mandate for Syria and Lebanon, worked in the vulnerable late-colonial regime of the Protectorate of Morocco, and from the mid-1950s functioned as a development aid expert. To understand the work of Écochard in the period from 1953 onwards it is important to situate it within a new regime that was emerging right after the Second World War, when an increasing amount of nations were shedding their colonial ties and becoming independent. This independency was both a blessing and a curse. For many of the young nation-states the newly gained independence was also paired with new responsibilities. The technical expertise in many realms of social and economic life that was previously offered by the colonizer had now left the territories and there was a need to redefine this technical knowledge, among others in the field of architecture and urban planning. Against this background the post-war period saw the emergence of a new regime of architecture and urban planning. Under the header of ‘development aid’ or ‘technical assistance’, large international organizations such as the United Nations, national governments of developed nations – from the East, the West and non-aligned blocks – and philanthropic organizations such as the Ford Foundation started to commission architects and urban planners.7

The Emergence of a New Expert

Urbanization has created problems of great magnitude and complexity that have gone beyond the capacity of individual experts. Teamwork is needed, and teams operate better if they consist of different specialists applying their skills for a common objective. What we hope to produce is not a new profession, but a new kind of training which makes members of the existing disciplines conscious of urban growth problems and trains them for cooperation in effective teams.8

In these terms German-born planner Otto Koenigsberger described the emergence of a new kind of expert that – as a result of the new regime of commissions – had started to populate the networks of transnational planning in the post-war period. Indeed, the internationalization of development aid was accompanied by the emergence of the figure of the ‘international development expert’, who in many instances had simply switched sides; from working for the interests and from the perspective of a single imperial capital they now came offering a sublimated notion of multinational assistance to the Third World. Almost all former colonial territories were experiencing urban growth at unprecedented rates, usually resulting in widespread informal urbanization. Often already tense due to the way national boundaries were drawn, this process of urbanization could quickly exacerbate ethnic conflicts, leading to major internal refugee problems. To face these challenges – and given the lack of indigenous planning expertise – architects and urban planners functioned in international teams of development experts, working transnationally as well as transdisciplinary.

Particular for this new regime of post-colonial experts was that the expertise that they were relying upon had been developed in colonial contexts. After the big wave of decolonization in the immediate post-war period many architects and urban planners had returned to their home countries. They represented a resource of ‘colonial expertise’ that was often conceived in conditions of emergency and displacement, but above all that was dormant and ready to be activated as development aid. Well-known names such as Jane Drew and Maxwell Fry, Victor Bodiansky, Otto Koenigsberger and Constantinos Doxiadis became part of this new class of experts that started to travel the globe and practice architecture and urban planning in the name of development aid.9

Redefining Universalism: The Case of Karachi (1953-1955)

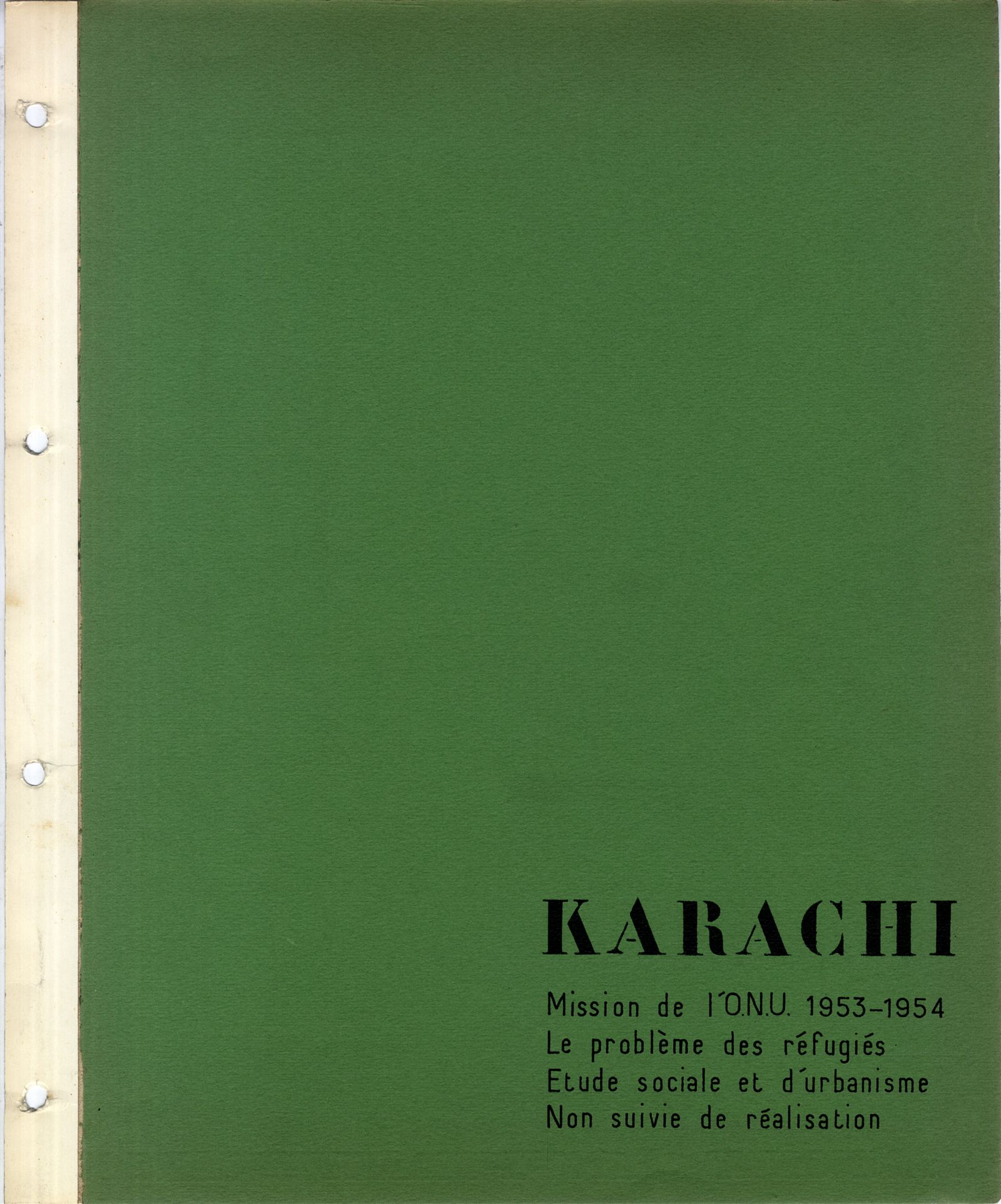

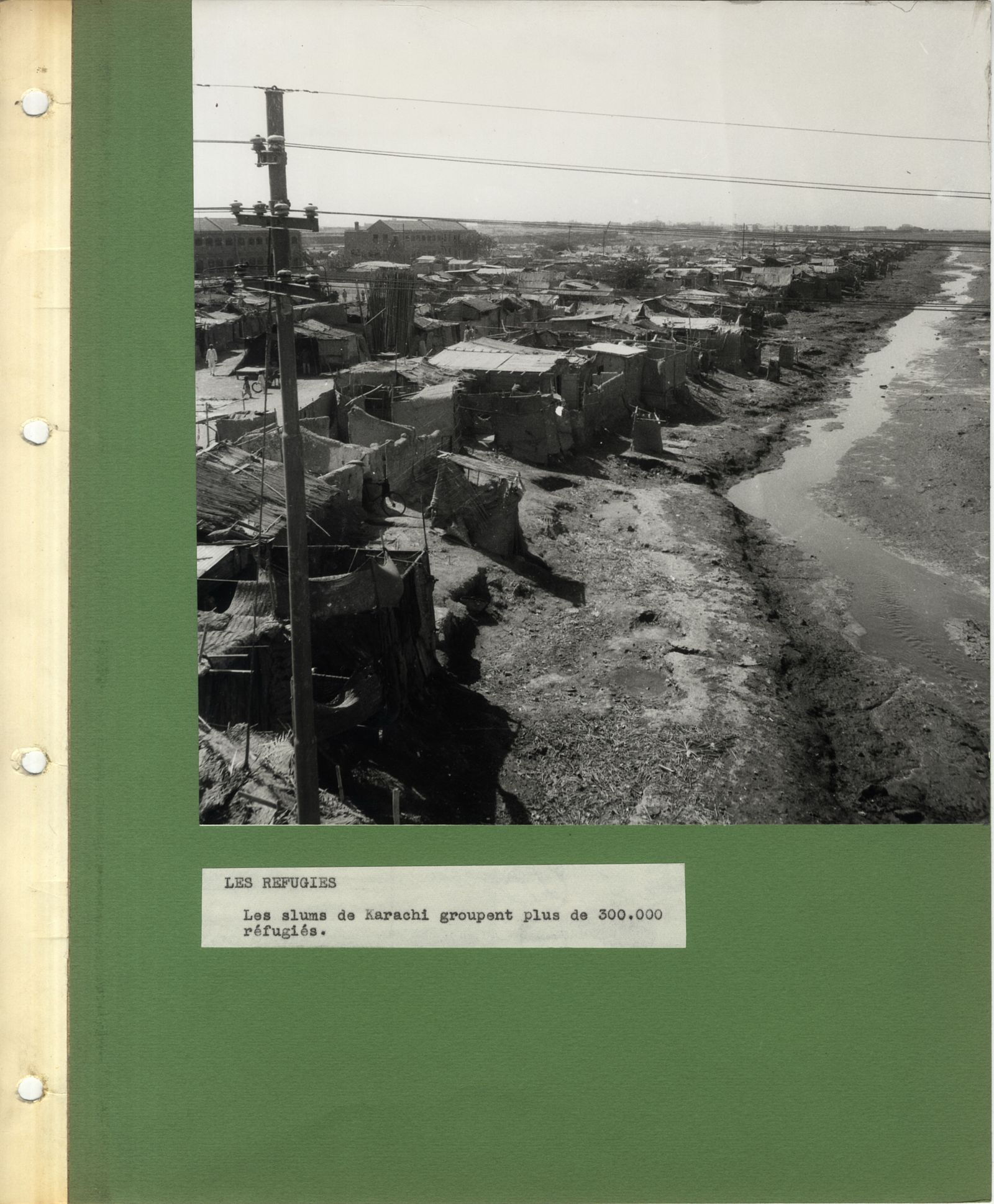

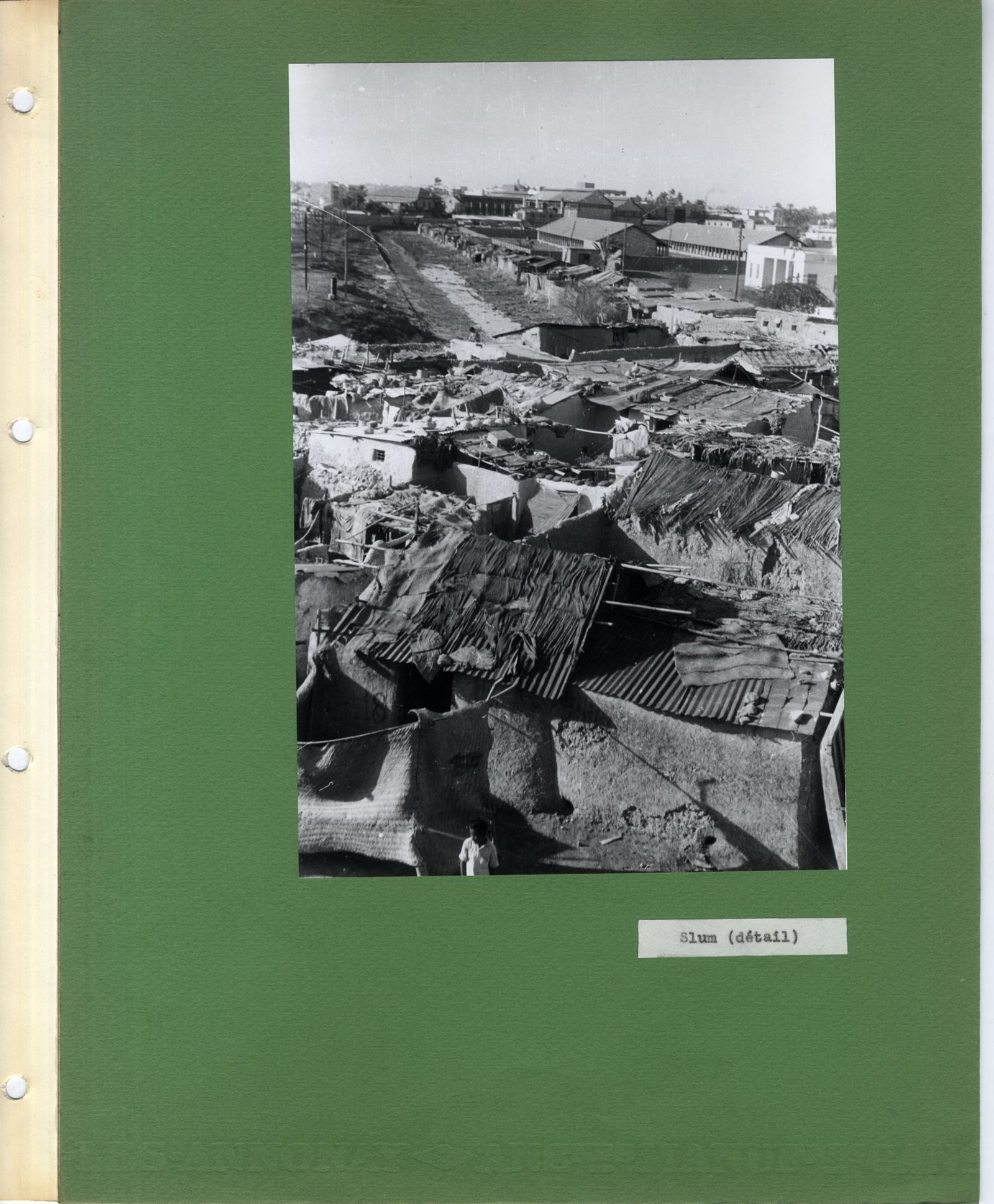

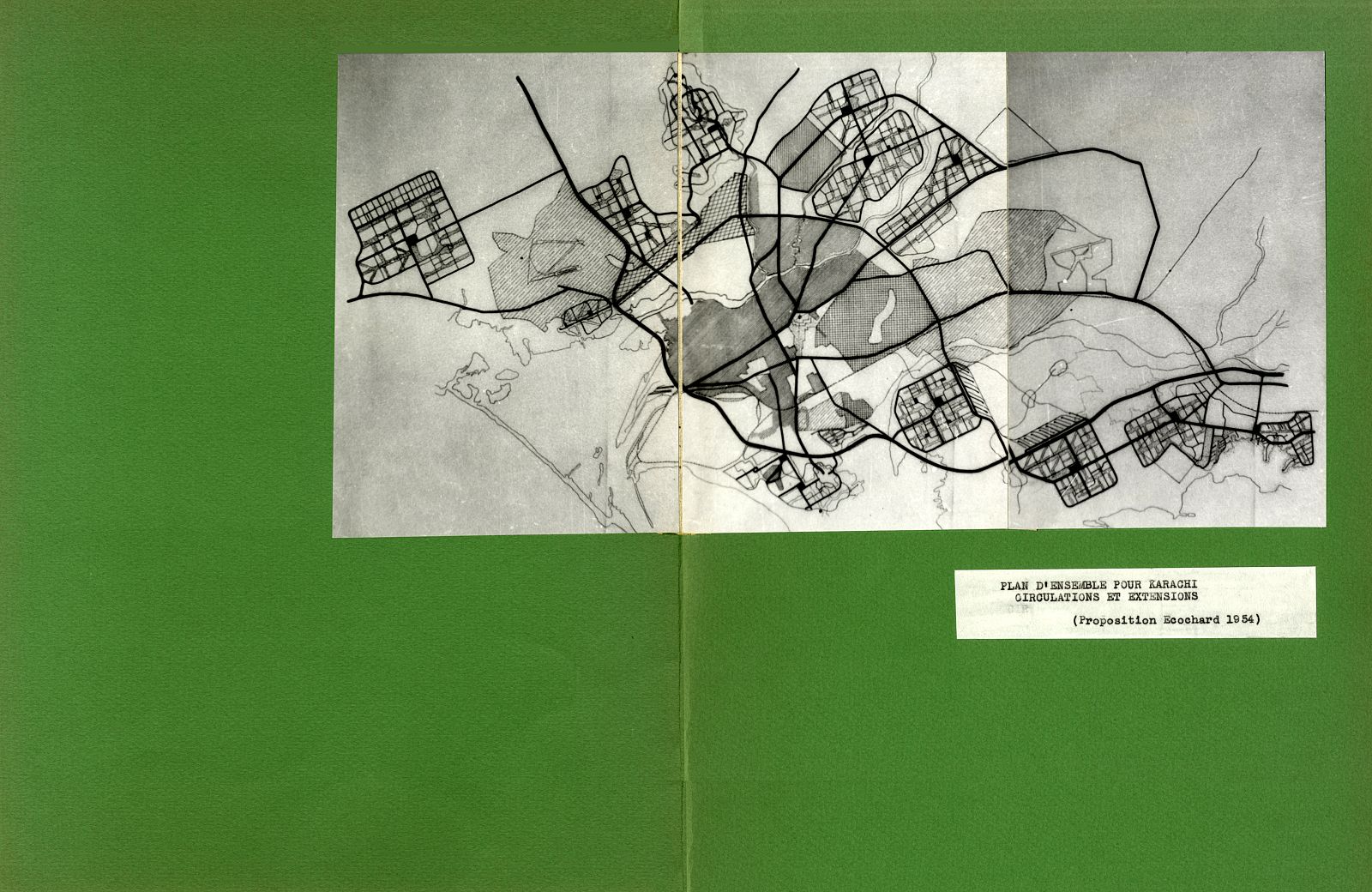

This was also the case for Michel Écochard who was sent in 1953 by the HTCP Section of the United Nations on a mission to Karachi, Pakistan. Écochard was asked to engage with the problem of the poor housing conditions of the refugees that had fled to Karachi after the decolonization of the British Indian Empire. Though he was a strong believer in the modernist principles of the CIAM, his visit to Karachi would engender a sophisticated criticism of the universalist claims – the idea that generalized standards of housing could be defined that could be applied all over the world – so characteristic of canonical modernism. In his report on Karachi Écochard attempts to introduce another understanding of modernity, which is more rooted in local characteristics, more indigenous. The importance of local conditions becomes a central point of discussion in his report on ‘Refugee Problems in Relation to Town Planning in Karachi’, published in 1955 for the United Nations. In this report Écochard holds a plea to understand urban planning and architecture as ‘human sciences’ that are rooted in a profound understanding of the requirements, environmentally, economically, socially and most of all practically of a rapidly expanding, and predominantly widely impoverished new urban population. As a result Écochard claims that it is impossible to strive for universal standards and norms, but that the particularities of each urban condition require an in-depth investigation of its full spatial and social characteristics.

Écochard not only criticized the universalist attitudes of high modernism, but also the existing modes of housing design in developing countries, blaming a number of established standards for their ineffectiveness and their focus on a Euro-centric understanding of modernity:

Another prejudice that may be encouraging this deplorable scattering is the notion of the ‘English cottage’ so pleasing to the engineers who omit to face the problem (for which, furthermore, they lack all means of evaluation). They think the whole of the population could be accommodated in villas. They believe this to be a modern datum of town planning, which on the contrary this notion – so pleasing in certain circumstances – is actually everywhere out of date because of the importance of new human concentrations.10

Écochard’s comments illustrate his criticism of how Western experts, in conjunction with the housing models and typologies that they were proposing, consciously or unconsciously imported a particular idea of modernity. These Western models of thought were not only conveyed by foreign experts, but also by local experts who had been trained in the West:

In Karachi, the majority of technicians I met – related to town planning or building construction – had been trained in England or America and had come back home filled with the security attached to the acquisition of occidental science . . . And so what could be expected happened: except for some rare exceptions – corresponding to the average percentage of superior beings in any country – the majority of Pakistani town planners or engineers merely carried out the teachings acquired in the West without either discrimination or adaptation to the new economic and social conditions.11

Against this background, Écochard makes a plea for a better education in urban development and design that would not promote inappropriate occidental ideologies but be particular to the local condition.

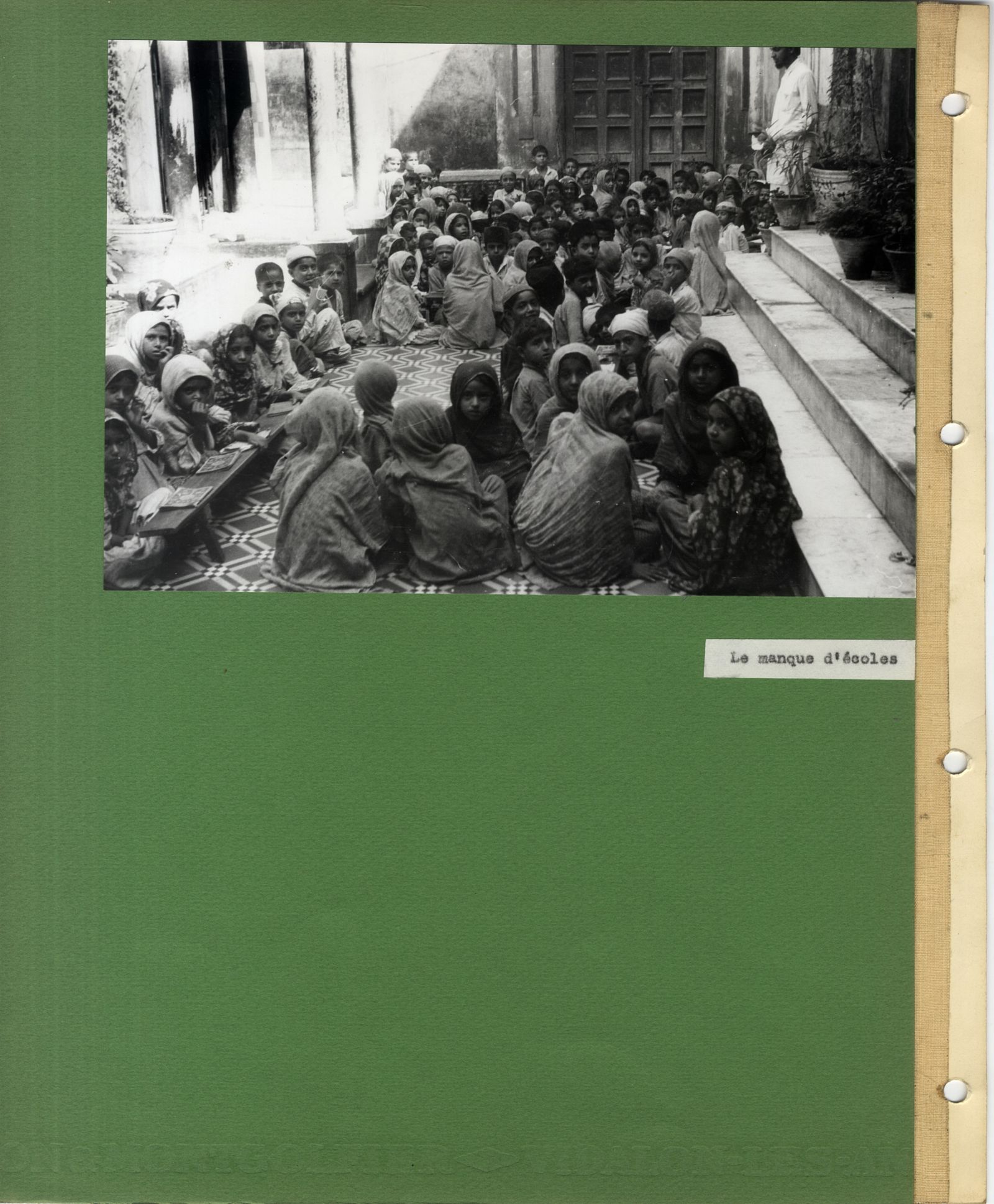

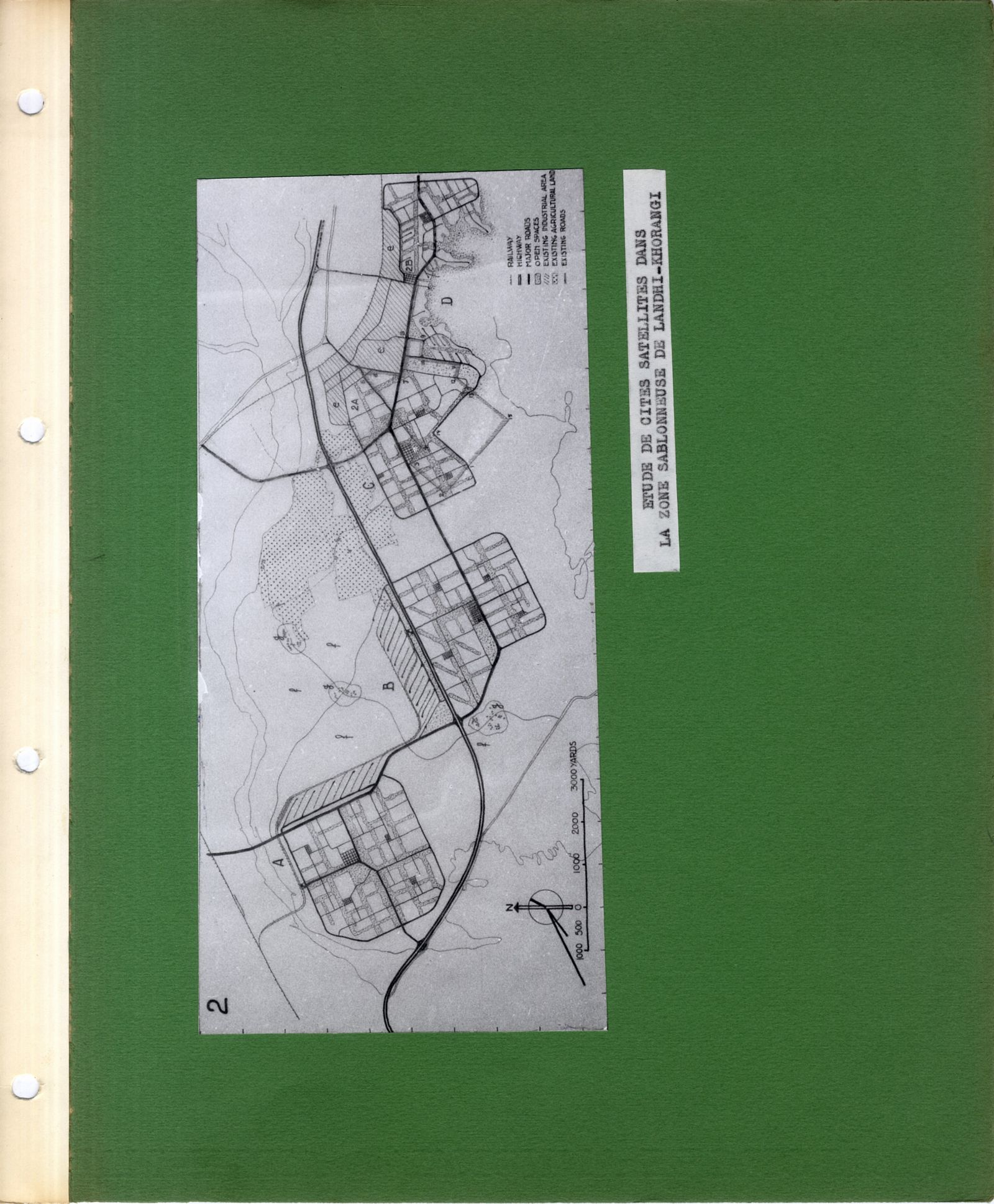

On a broader level, Écochard’s intention was to investigate the possibilities to conceive of a different definition of modernity that could form the basis for new concepts in architectural design and urban planning. For the development of such a new attitude to modernity, he could rely on his previous experiences and especially on the knowledge that he had conceived as a director of the Service de l’Urbanisme in the Protectorate of Morocco, a position that he held from 1946 to 1952. A particular characteristic of Écochard’s planning and design approach in Morocco was that it started from a very detailed survey that consisted both of a qualitative and a quantitative examination of the terrain.12 This survey approach would also inform his work in Karachi. In the first report that Écochard and the other team members composed, entitled Karachi: Mission de l’ONU 1953-1954. Le problème des refugiés. Étude sociale et d’Urbanisme, the survey is the prime element. Écochard believed that it was the task of the urban planner to profoundly engage with the different logics and rationales of the terrain. The report comprises a photographic mapping that identifies the various problems that are at stake in the housing condition of the refugees in Karachi, including the bad sanitary conditions, the poor building quality and the lack of collective infrastructures such as schools in the slums. This photographic, more qualitative, mapping is complemented with more statistical data on the economic, social and technical characteristics. Together these qualitative and quantitative data form a knowledge base that allowed Écochard and his fellow experts to conceive approaches to the improvement and modernization of the urban condition that reach beyond sheer Western models.

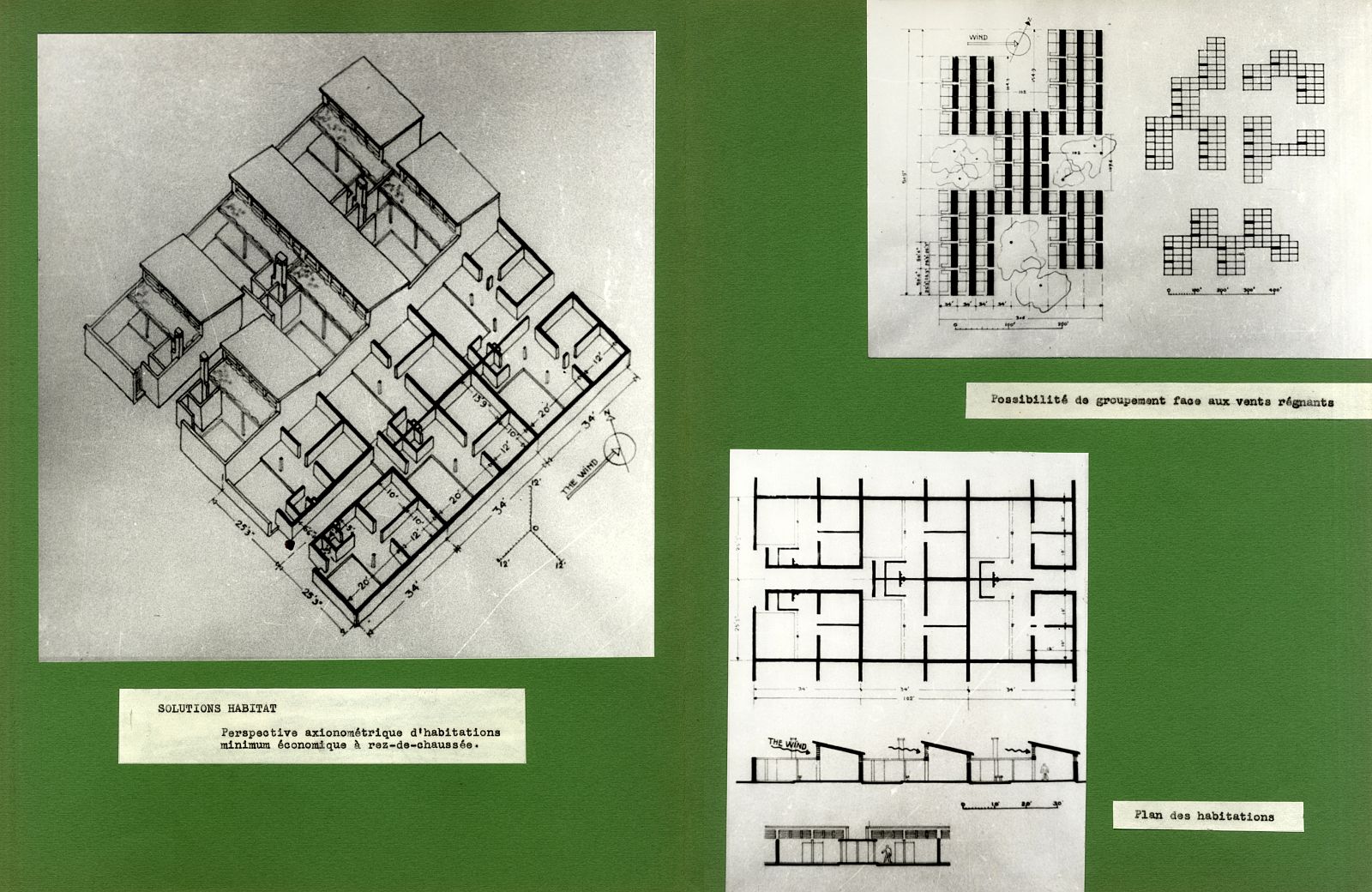

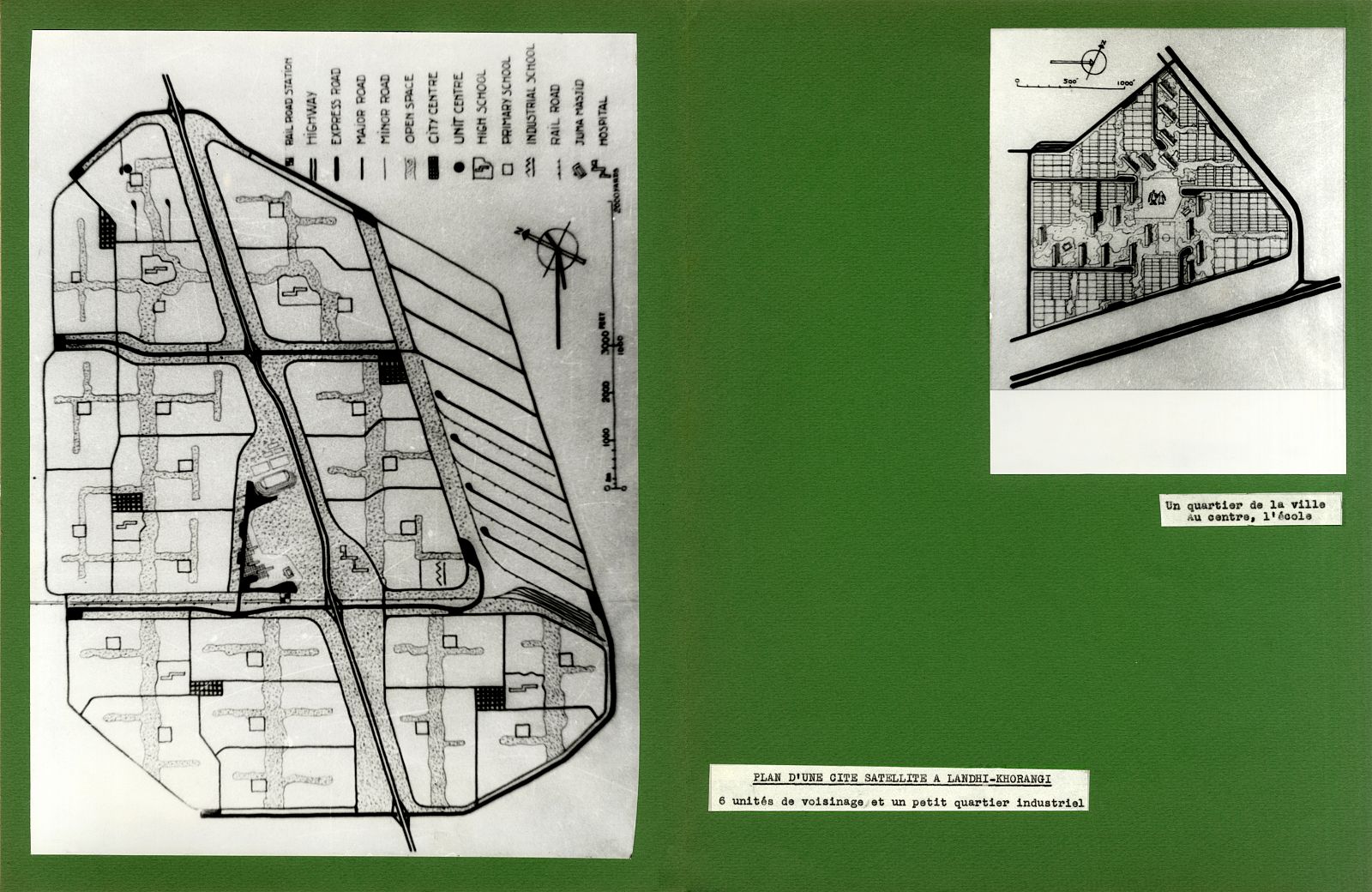

When Écochard starts to suggest a way of intervening in the poor dwelling conditions of Karachi, he relies on a planning instrument that he used earlier and that offers him the opportunity to combine a modern rationalized approach with attention for local conditions. For the new housing developments he suggests, just as in many of the Moroccan cities where he had worked previously, a regular ‘grid’ as the base for his urban and architectural intervention. The choice for the grid as a main planning tool was no coincidence. Écochard approached the question of the affordable house not through the lens of the ‘prescription’ of Western models of modern living but through the perspective of ‘accommodation’ of local dwelling practices that were being modernized. To him, affordability was not a matter of preconceived recipes of construction, but of allowing the house to evolve with the changing social needs and economic possibilities of the family that inhabits it. Out of this perspective it is typical for Écochard that the idea of provisional shelters, which can be realized rapidly with local construction techniques, is combined with a more perennial idea of the housing neighbourhood. Indeed, in a first instance the grid is conceived as no more than an urban receptacle. As several of his diagrams illustrate, the grid functions as a way to structure the existing shacks and the rapidly built temporary housing units, and to compliment them with the basic infrastructure of water and sewage.

In a second instance, however, the grid becomes the organizing basis for a new and full-fledged neighbourhood that starts off as a lowrise environment but can evolve into a high-rise configuration. This neighbourhood is characterized by an elaborate hierarchy of public spaces, as well as by a dense pattern off collective functions such as various schools, hospitals and cultural amenities. The grid offers a rational basis on which these different functions, but also particular housing typologies, can be arranged. Each cell of the grid represents a permanent low-rise house that is typologically adjusted to the climate and patterns of living in Karachi, in so far that it is composed of indoor and outdoor rooms with different heights. Due to this typological choice the higher indoor rooms can act as wind catchers, which creates air streams and cross ventilation in the house.

Écochard’s idea was that the grid would offer the permanent frame for the gradual evolution of the local dwelling practices. In his viewpoint it would be transformed into different dwelling typologies, following the aspirations, needs and possibilities of the local families. The grid would offer an urban counterform that accommodates the changing dwelling practices and thereby contributes in a more open fashion to the modernity of the place.

Affording the City: Fria New Town (Guinea, 1956-1958)

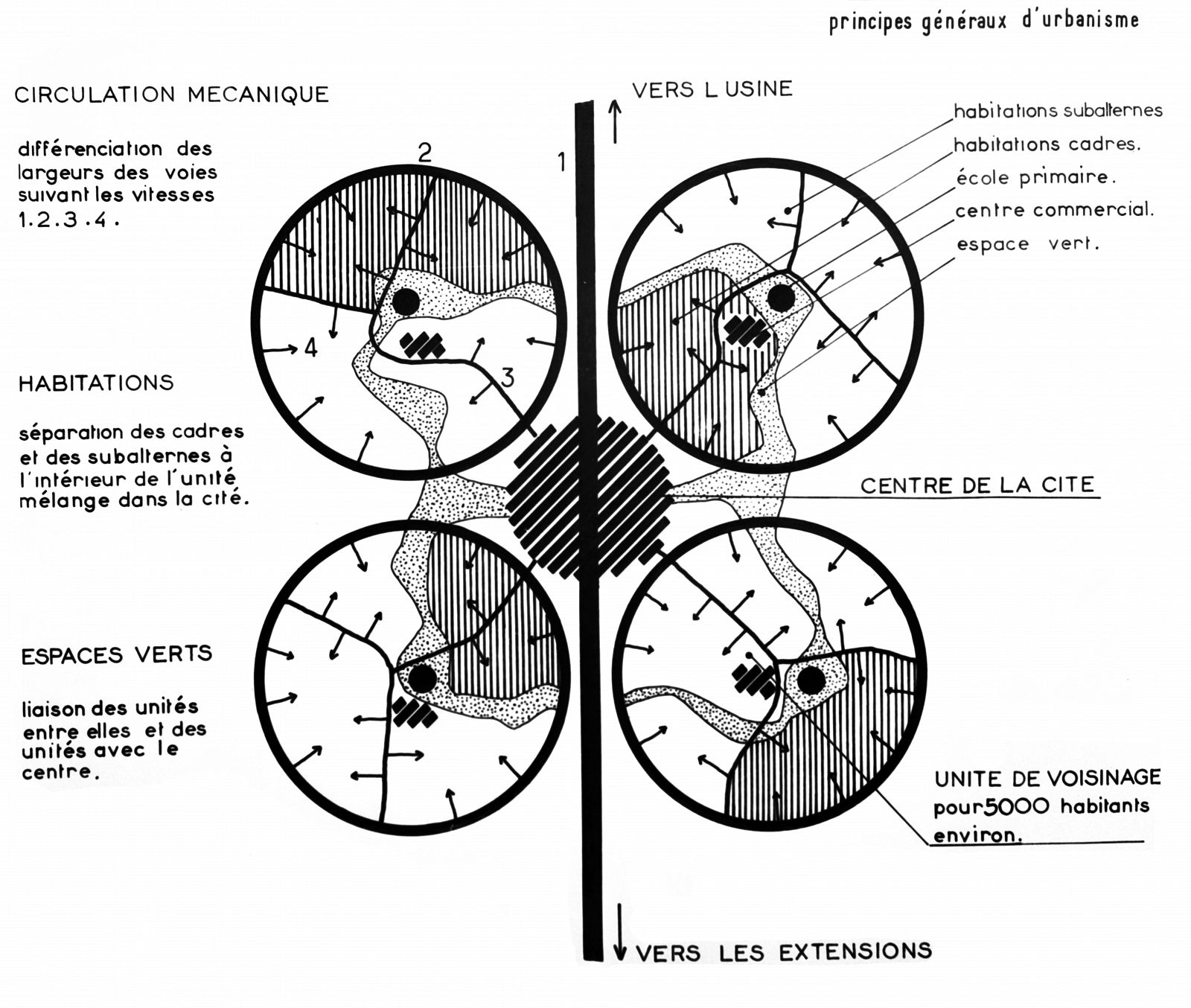

That expertise, including concepts and approaches of housing, easily migrated between late-colonial and post-colonial contexts illustrates the project for Fria. While Écochard was already working several years as a post-colonial expert aiding young nation-states with their planning and design issues, he was commissioned in 1956 to design a new town for the 20,000 future employees of the bauxite extraction factory of French aluminium company Péchiney in the vicinity of Sabendé on the late-colonial territory of Guinea. At first sight the new town is planned according to modernist principles, keeping a distance from the factory, the commercial and cultural functions grouped and placed centrally between the different neighbourhood units, and car and pedestrian circulation clearly separated. However, at closer scrutiny the plan for Fria seems to hold a very particular definition of affordability; defined as the access, or in the words of Henri Lefebvre, ‘right to the city’.13

Though access to the city might seem as an obvious given in the planning of a new city, it was all but evident in a colonial context. Typical of the colonial city was that there was a strong two-partite division between the city of the colonizer with all of the central cultural functions and the city of the colonized – kept apart by a so-called zone neutre or cordon sanitaire. It is quite obvious how in the urban plan that Écochard is proposing this divide is simultaneously maintained and contested. A schematic representation of the urban plan illustrates how each of the neighbourhood units is dived intp two parts, one for the Western managerial staff and one for the so-called indigenous ‘subalterns’. It is typical for Écochard that he conceives these units as fluctuating entities that do not fully rehearse the typical colonial divide between colonizer and colonized, but rather alternate in their proximity to the city centre. On one occasion the French white collar workers will have the privilege to live close to the city centre, on the other the indigenous working men and their families. A system of sinuous green zones connects the various units with each other and links them to the commercial centre. Écochard writes besides the diagram: ‘Separation between the managerial staff and the subalterns in the neighbourhood unit, but mixture in the city.’ While maintaining the colonial categories their spatial implications are contested.

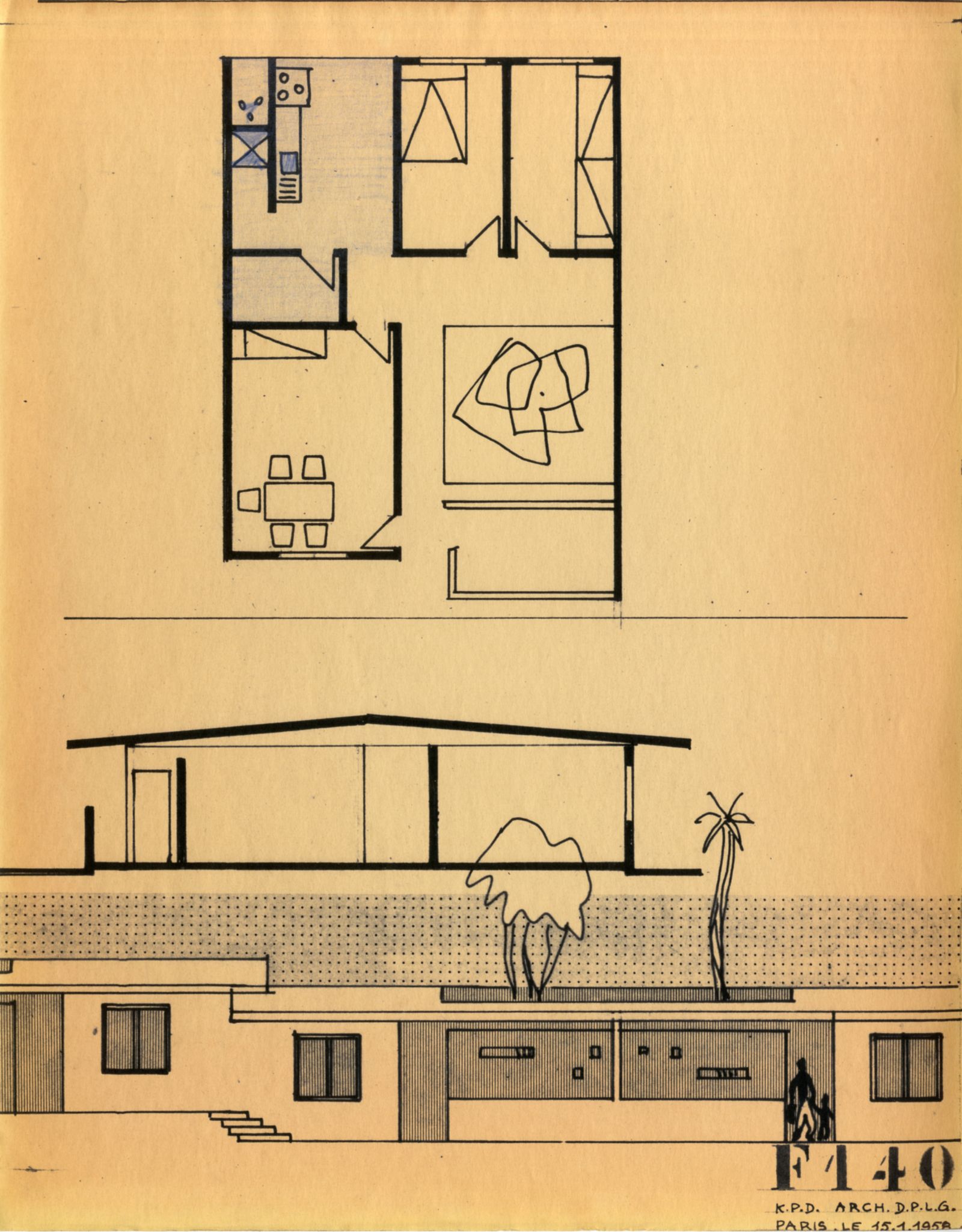

The high-rise living blocks foreseen in his plans were contracted to the then-well-known French office of Lagneau, Weill and Dimitrijevic, while the design of the individual housing units was assigned to KPDV.14 This young office was established in 1955 by Michel Kalt with two young fellow architects, Daniel Pouradier-Duteil and Pierre Vignal.15 KDPV presented their work in Fria as a way to counter the colonial enterprise and offer a social return to the local population:

Africa’s development is at the order of the day. The exploitation of its natural resources may result in the years to come in the country’s industrialization and the rapid growth of large cities. Now if we want to bring something to Africa in return for what we take, we must focus on the social and human requirements even stronger than on the material and economic interests that attract us.16

The way to offer such a social return was by providing comfortable and affordable housing. Each individual household was provided with a simple house that complied to Western living standards under a large, projecting roof manufactured with aluminium produced from the bauxite extracted on site by Péchiney. For the design the architects of KPDV collaborated with famous French engineer Jean Prouvé, who they had encountered in French avant-garde circles. Prouvé had experimented with industrialized building methods in France and in Africa. For Fria he developed an innovation in tropical construction: a process to fabricate an aluminium roof in one piece, thus avoiding water intrusion on the level of the joints of different building components. In Fria these roofs represent a continuous shield that protects from the elements and allows for cross ventilation and for a flexible organization of the various components of the house.

While the housing types were for the most part based on Western dwelling practices and building innovations, the architects of KPDV also made an effort to acculturate them to local conditions. The different houses are gathered in small clusters of about 15 houses that, according to the architects, echo existing rural morphologies as well as local notions of social life. The actual typologies of the houses repeat the traditional layout of a central and more open living space that is encircled by different other rooms. In addition, all houses were given a double orientation with entrances on both sides of the house that connect to the central living space. Despite the modern environment, this made it possible to maintain the traditional distinction between the women’s and the men’s parts of the house, between the domestic and the public sphere of the dwelling environment.

Both on an urban and on an architectural scale level, Fria New Town would turn out to be a balancing act; between colonial and postcolonial spatial patterns, between traditional and modern ways of dwelling. Fria is an exercise in the mediation of these different categories and the notions of affordability related to them, not in theoretical terms but through actual architectural interventions.

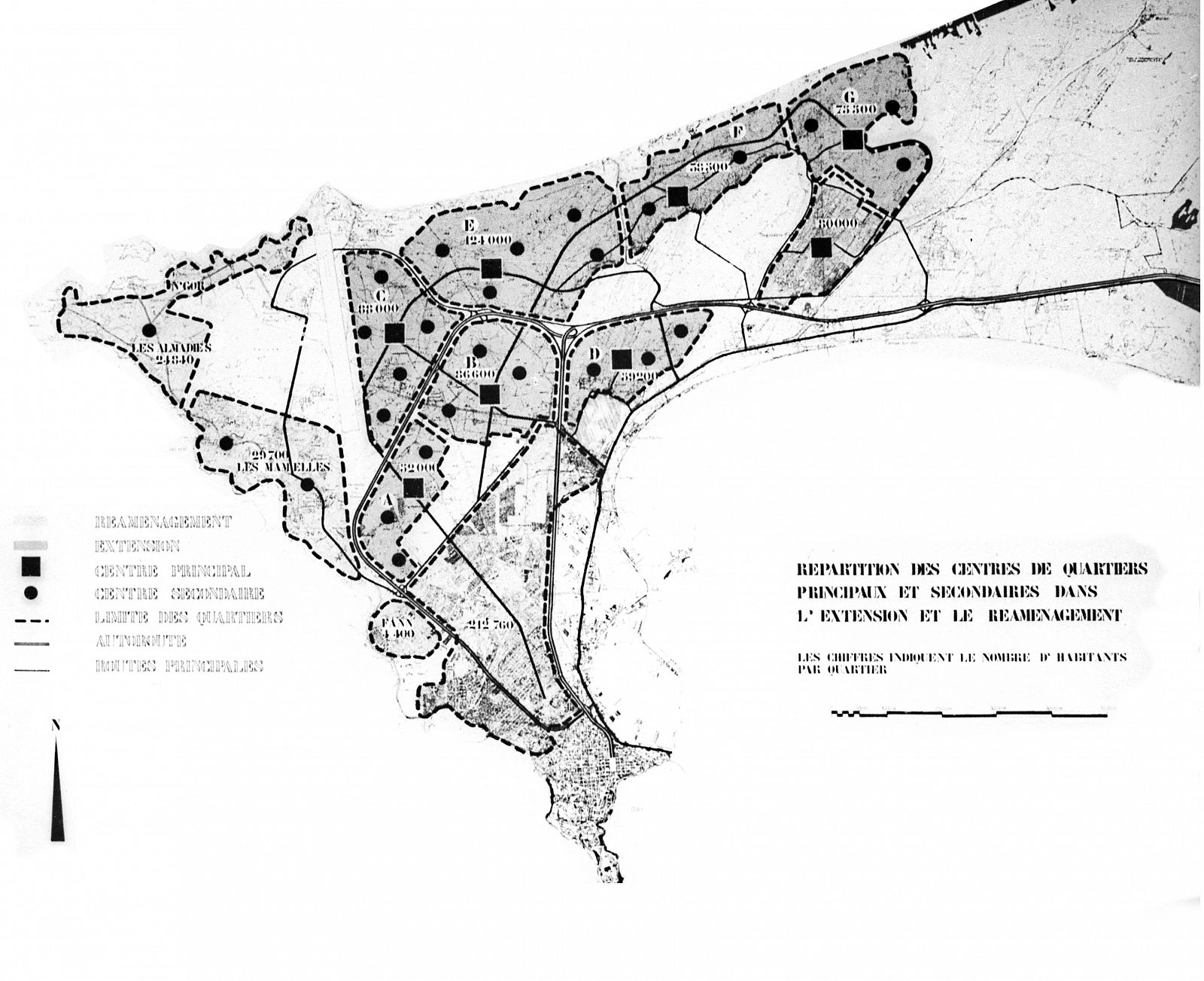

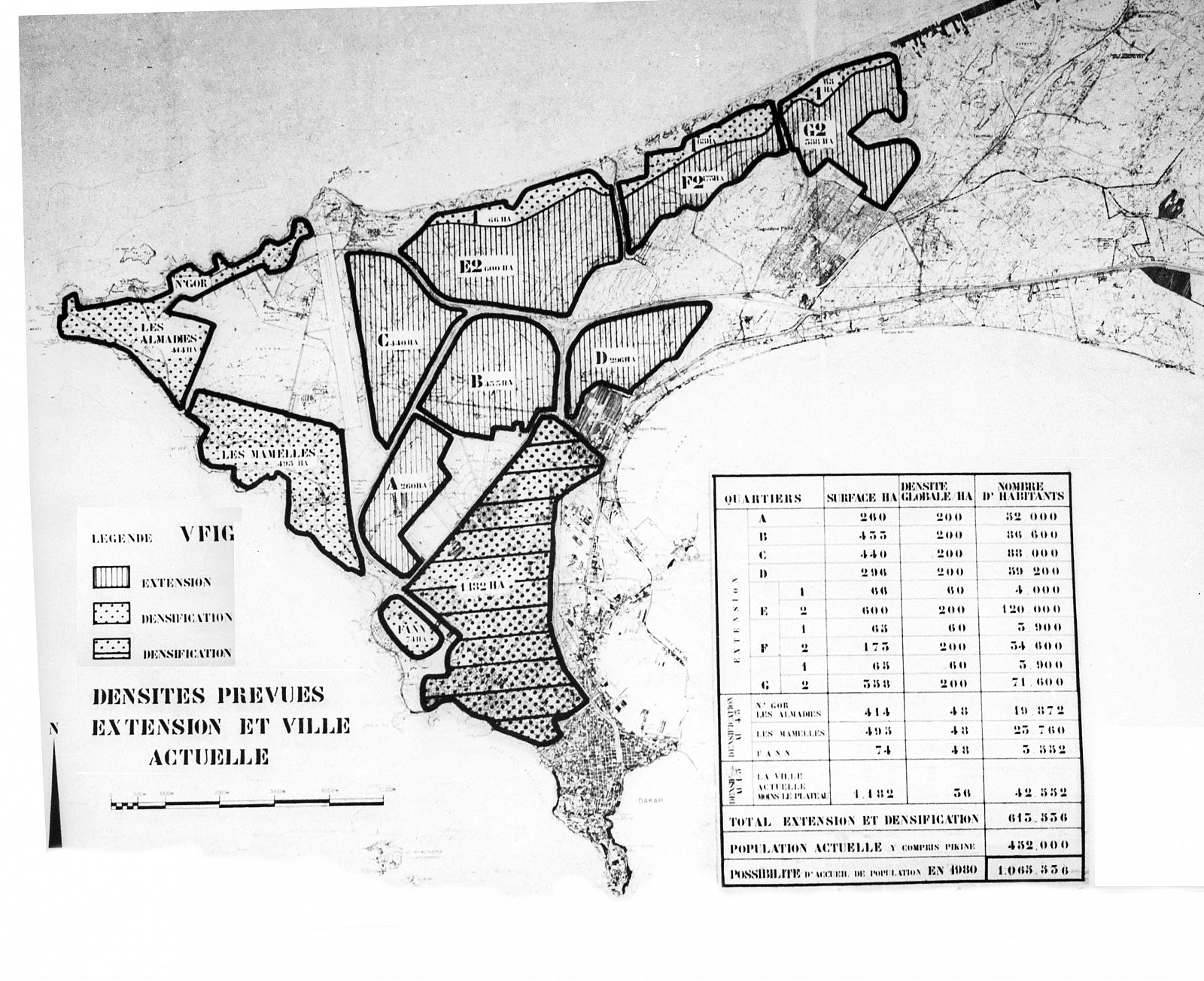

Contesting Spatial Logics: Dakar Development Plan (Senegal, 1963-1967)

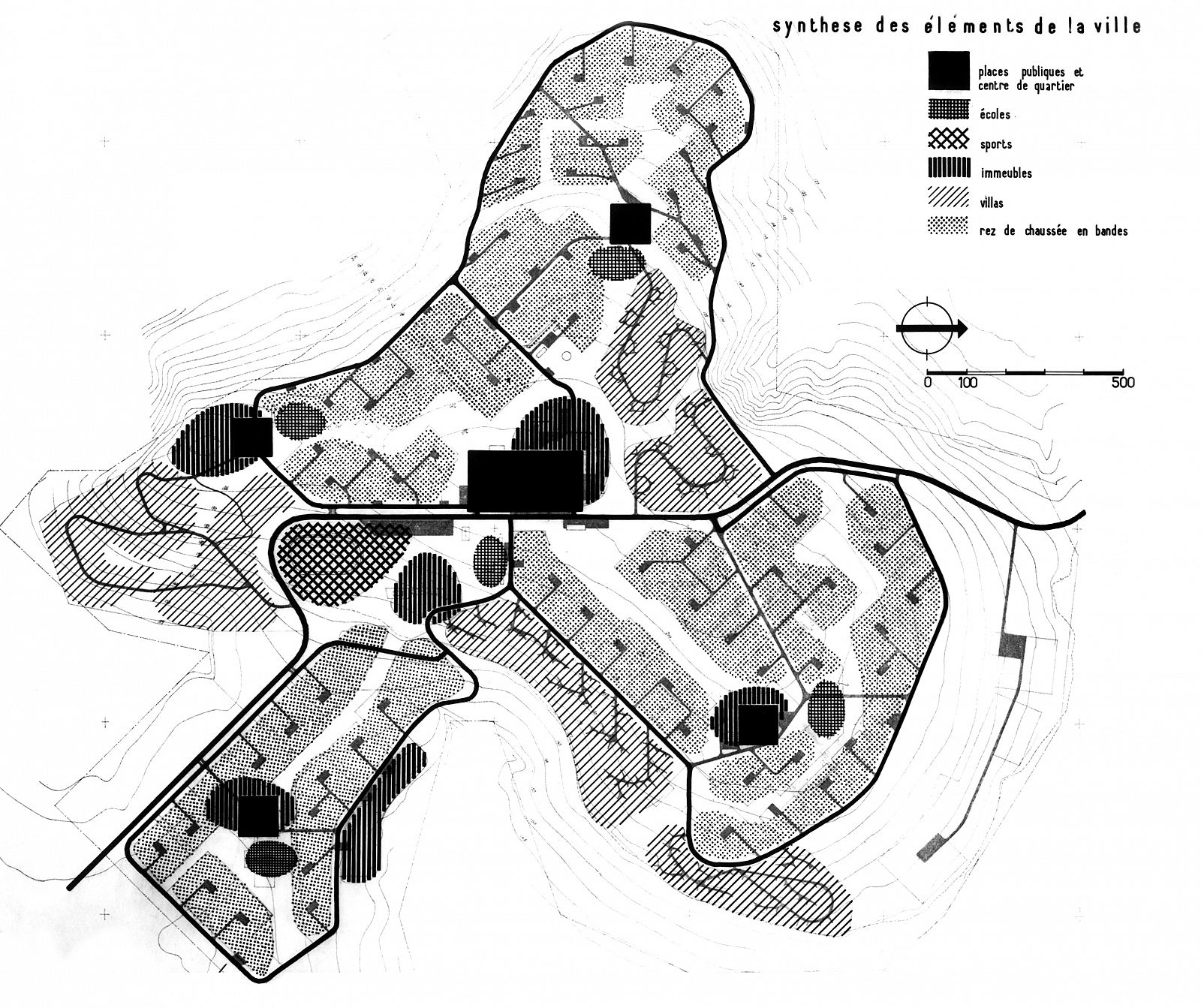

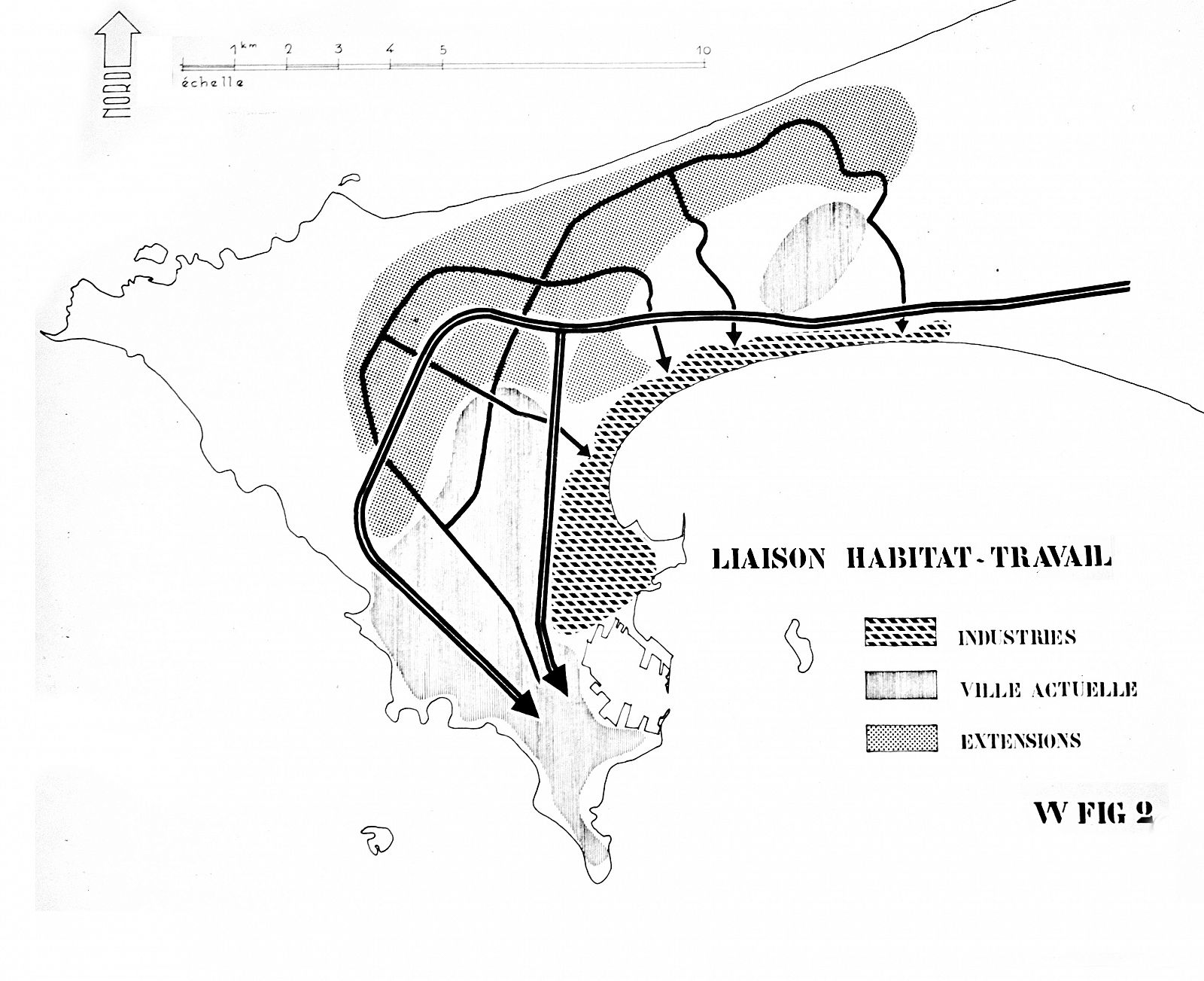

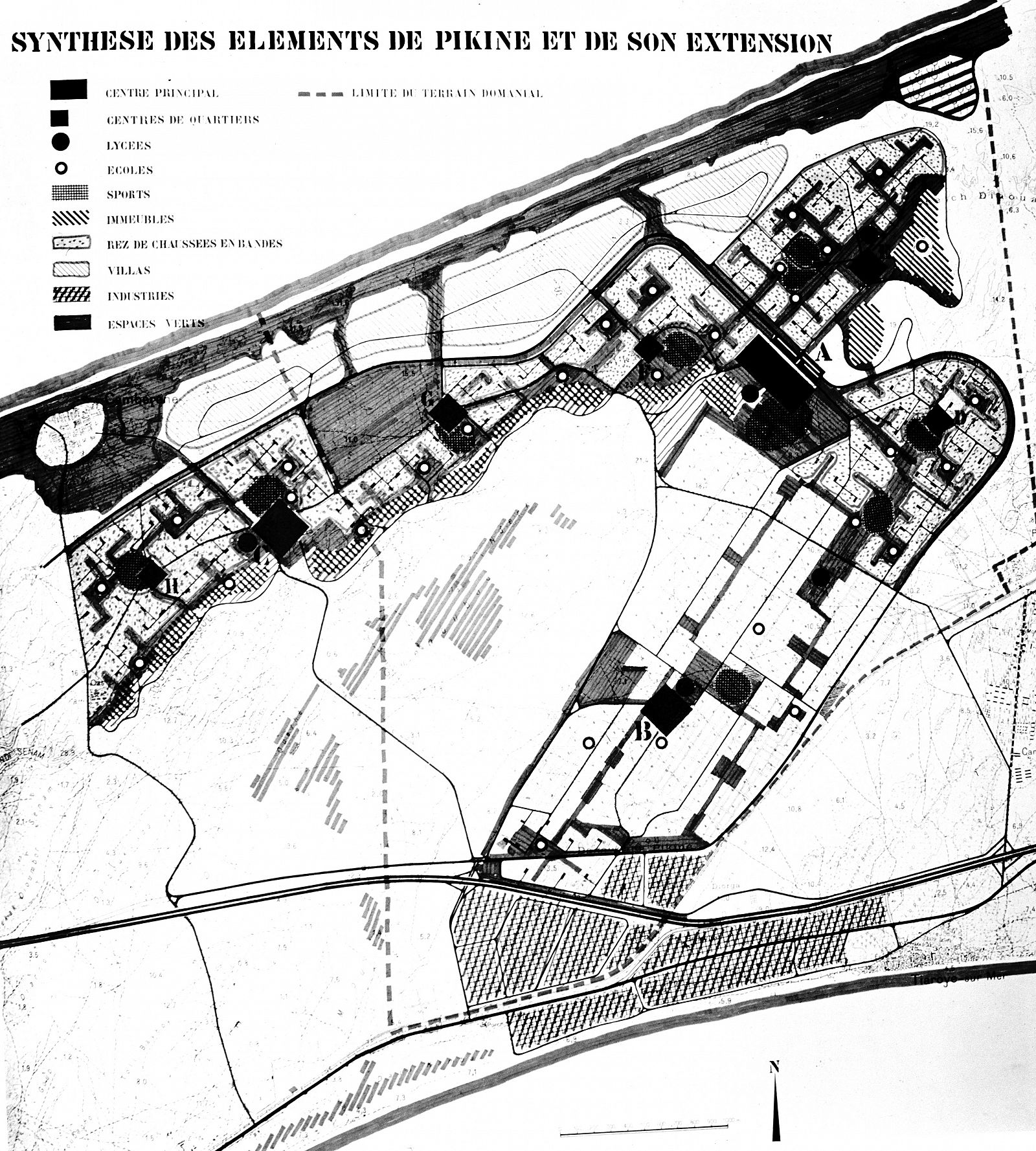

A third occasion on which Écochard deployed his specific approach and tools is when he was invited in 1963 to design the master plan for the city of Dakar, the newly established capital of Senegal after its independence from France in 1960.25 The plan was drawn up in the expectation that Dakar would continue its steady growth and reach a population of 1.2 million by 1980. In Dakar, just as in Morocco, Écochard identified rural-urban migration as the central point along which new urban development had to be considered.17 His project suggests the renovation of the old city and existing neighbourhoods (Reubeus, Médina, Grand Dakar, Pikine), but also encompasses the design of new districts that could house the continuous stream of immigrants.18 Écochard criticized the Senegalese policy of deguerpissements (forced removals) which removed bidonville settlements in central Dakar, relocating them to Pikine, a large region outside of the city, away from facilities, public services and jobs. The cleared spaces were developed into wealthy modern housing developments. Pikine, therefore, became a central focus in Écochard’s development plan for the Dakar region, redefining the satellite city as a ville nouvelle that would merge with the central city during his 15-year development plan.

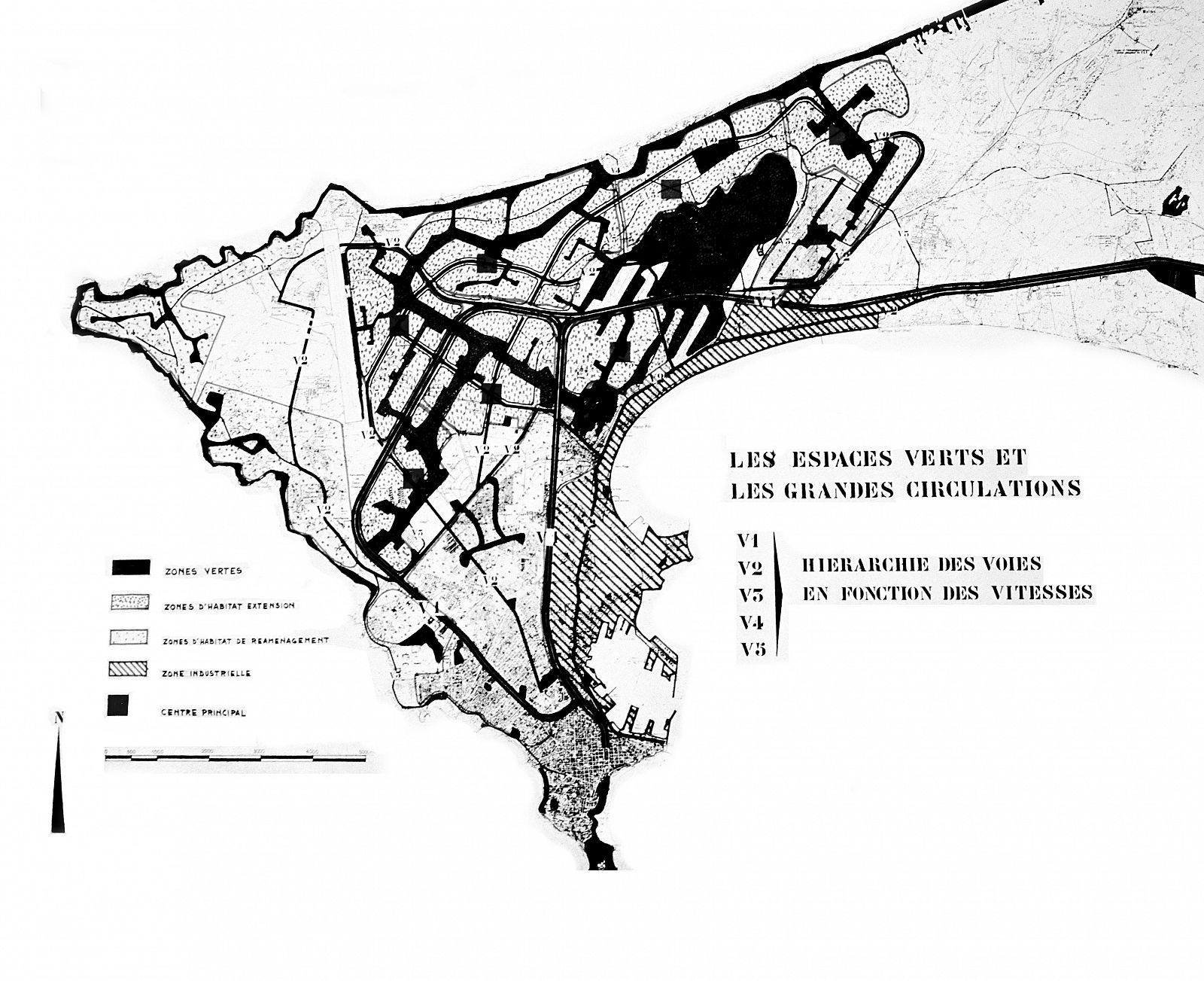

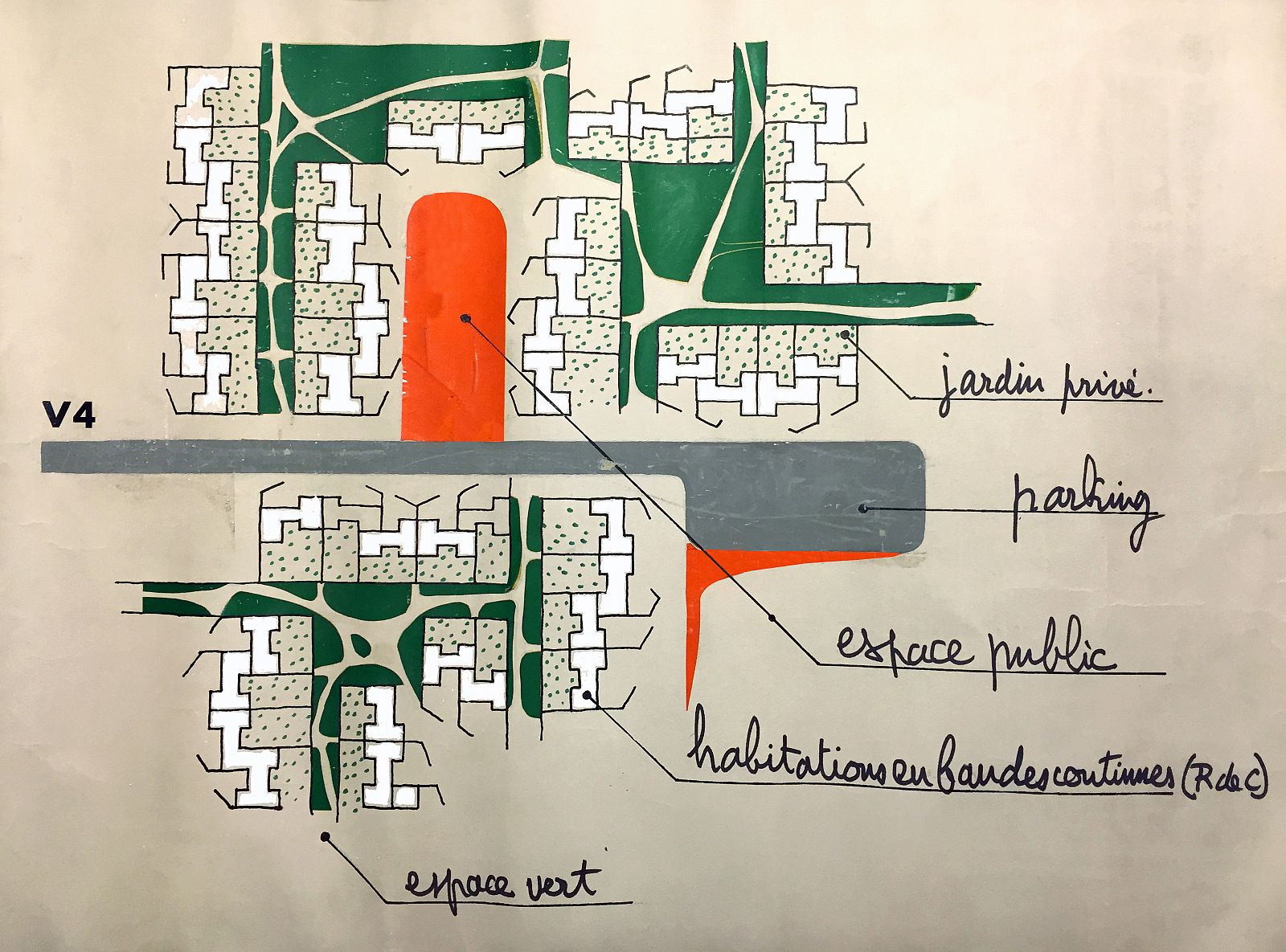

In Senegal Écochard returns to the earlier established planning instruments. The starting point is an encompassing survey, pursued during a period of three years, that maps the different rationales and plans of urban development in Dakar. Through photography – from the ground and from the air, but also through infographics, Écochard established a set of perspectives on the urban condition of Dakar, which functioned as a knowledge base for the proposal of interventions. Typical of Écochard is that his plan for intervention was foremost focused on developing a network of roads and services, the ‘hardware’ of the city that would provide the urban structure, in which the ‘software’ could develop over time and to meet the needs of the modernizing urban communities. The plan is based on a hierarchy of road systems, with a ring road following the contours of the peninsula and a secondary slower road system that would be integrated with pedestrian and cycle travel. The double system interweaves the various neighbourhoods, providing fast and slow transit between the different districts.

Besides this hardware, Écochard develops a regular grid that functions as an underlying basis for the planning of the city’s housing. In Dakar the grid is used to integrate new urban neighbourhoods into the context of different earlier urban interventions based on Hausmannian ideals. The grid is conceived as a complementary and binding element for these interventions and creates as such the new urban project for Dakar. Just as in Morocco, the grid functions as a continuous basis that absorbs the evolving exigencies of the terrain and the situation. The enormous urban growth of Dakar is structured along an idea of ‘neighbourhood units’ that are characterized by a refined hierarchy of public spaces and would form larger housing neighbourhoods that would offer the essential facilities, including schools, markets, shops, community and religious centres. However, while in the Protectorate of Morocco the grid was perceived as a way to deal with the bad housing conditions of new urban immigrants, in Senegal it becomes the foundation for a modernization project that also encompasses the development of industry and tourist facilities as well as educational facilities, an Olympic stadium and a mosque. The Écochard Grid binds these various elements of work, leisure and everyday life, of profane and religious spheres, into a figure for a modern African city for the greatest number.

Écochard’s intervention was widely critiqued by local planning authorities and was not well received by cooperating consultants. In his turn Écochard criticized the Urban Planning Department of Dakar for their lack of enthusiasm in the development of Pikine and was angry about changes made to details of his plan without his consultation. He criticized the bureaucratic administration of the FAC development agency that only aimed to please and not truly provide real practical help. Écochard finally withdrew after the housing authority SICAP made major changes to the plan of a large neighbourhood plan, moving the public centre to the other side of a major road, making it inaccessible to the 50,000 residents, a decision driven by cost-effectiveness due to the influence of French investment bank CCCE. He wrote a series of very emotional letters to president Senghor about the issue and in March 1967 withdrew as urban planning consultant for Senegal, calling his mission a ‘complete failure’. Écochard was convinced to finish his plan for Dakar, for the sake of the Senegalese people, but only under the condition that his name was totally omitted from any of the plans.

New Roles, Methods and Approaches for Affordable Housing

In spite of his disappointment in Senegal, Écochard would become during the 1960s and 1970s one of the major French voices speaking about, and involved in, planning and architecture as development aid – labeled by his once Syrian partner Samir Abdulac as an urbaniste tiersmondiste (a Third World urban planner). This new regime under which architects and urban planners were commissioned radically questioned their tools and approaches. Constantly shifting between contexts, working in a condition of displacement, Écochard used the survey as a very important tool with which to establish a relation with the local dwelling practices and patterns, but also to initiate a possible dialogue with local actors such as politicians and planning authorities.

The various projects discussed also show that transnational planners and architects were searching for different ways to involve local actors and their agencies. Écochard’s engagement with the politics of space, for instance in his reversal of the old colonial spatial divides in the plan for Fria New Town is but one way to uproot the hierarchies between different spatial agencies in the city and to arrive at a more inclusive model of urbanity. In addition, his insistence on focussing the attention of the designer on the hardware of the city and on rudimentary housing typologies that have a certain openness, illustrates how the agency of the urban planner and architect is positioned in an explicit relation to that of other actors in the built environment.

It also remains fascinating how in the projects of Michel Écochard and some of his fellow planners and architects new notions of affordable housing emerge. These notions reach beyond the simple conceptions of economic accessibility that were held by some managers and politicians. They take into consideration that affordability can include the possibility to pursue established dwelling and building practices in a new dwelling environment as exemplified in the case study of Karachi. They articulate affordability as the possibility of access to the social, cultural and public facilities of the city, as Écochard illustrated with his plans for Fria. And finally, they conceive affordability as the possibility to remain living in a well-known social structure while the city is being developed, as brought to the fore in the project for Dakar.

These alternative concepts of affordability were articulated several decades ago but have not lost their value. They stand today as notable examples of how from within the realm of architecture a new set of notions can be developed that complement the economic and managerial conceptions of affordable housing in innovative ways.

-

1This research on the United Nations and the HTCP was undertaken together with Maristella Casciato. An introduction to the various activities of the Housing and Town and Country Planning can be found in the various issues of the periodical Housing and Town and Country Planning (New York: United Nations. Dept. of Social Affairs, 1948).

-

2Adequate housing was recognized as part of the right to an adequate standard of living in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was approved by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948 and of which article 25 states: ‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and wellbeing of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing . . .’ It was confirmed in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

-

3Weissmann emigrated to the USA in 1938 and worked, among others, with Catalan architect Josep Lluís Sert, first on the publication of the book Can Our Cities Survive? (1942), followed by wide-ranging urban studies. Weissmann was crucial in linking local practice and regionalism to the European architectural avant-garde. At the HTCP section, his nationality was an asset: Yugoslavia, although a communist state, followed the path of non-alignment. This neutrality helped allay suspicions among leaders in the developing world that UN planners were simply pawns of one of the two centres of power. It also made it easier for planners on both sides of the Iron Curtain to participate in UN ventures.

-

4The list of contributors to the Housing and Town and Country Planning (HTCP) division is the testimony of this wide range of organizations that were involved. The pages of the periodical Housing and Town and Country Planning illustrate this broad variety of actors and present articles by first generation modernists such as J.J.P. Oud and Walter Gropius, and at the same time represent viewpoints by planners like Jacob Crane and Jacqueline Tyrwhitt.

-

5In its beginning years the bulletin was titled Housing and Town and Country Planning to evolve after 1953 to Housing and Building and Planning. See: Housing and Town and Country Planning (Lake Success, NY: Dept. of Social Affairs, 1948-1953). A catalogue of more than 400 movie titles illustrates the large film holding of the HTCP section, Housing, Building, Planning: An International Film Catalogue (New York: United Nations, Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs, 1956).

-

6See also M. Ijlal Muzaffar, The Periphery Within: Modern Architecture and the Making of the Third World, PhD Thesis (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Dept. of Architecture, 2007).

-

7The United Nations played a prominent role in this new regime. Together with other, often national, actors such as Poland’s Myastto project (a national planning and development organization) development cooperation). See also the theme issue of The Journal of Architecture: Lukasz Stanek and Tom Avermaete (eds.), ‘Cold War Transfer: Architecture and Planning from Socialist Countries in the “Third World”’, The Journal of Architecture, vol. 17 (2012) no. 3.

-

8Otto Koenigsberger, ‘The Problem Facing the Planner in the Tropics’, unpublished lecture given to the Conference on Tropical Architecture, March 1953, 4.

-

9Architects had always been crossing borders, working occasionally in other countries and cultures. However, in the post-war period there seems to be a kind of architect and urban planner emerging who works permanently across borders. Architects and urban planners, like Constantinos Doxiadis, Michel Écochard, Jacqueline Tyrwhitt, Victor Bodiansky, Jacob Crane and Otto Koenigsberger – to name a few well-known examples – developed a ‘global practice’.

-

10Michel Écochard, Refugee Problems in Relation to Town Planning in Karachi (New York: United Nations, 1955), 9.

-

11Ibid, 10.

-

12For a further exploration of the survey in the work of Écochard see: Avermaete and Casciato, Casablanca Chandigarh, op. cit. (note 8).

-

13Lefebvre, Henri, Le Droit À La Ville (Paris: Anthropos, 1968).

-

14Atelier LWD was an architecture studio led by Guy Lagneau, Jean Dimitrijevic and Michel Weill that was active from 1952 to 1985. For an introduction see: Joseph Abram, ‘Le rêve du réel. Guy Lagneau, Michel Weill, Jean Dimitrijevic, Jean Prouvé et Charlotte Perriand: de la Maison du Sahara aux écoles du Cameroun’, Faces (Geneva), no. 37, 1995, 48-54.

-

15For an extensive introduction to this office see Kim de Raedt, ‘Shifting Conditions, Frameworks and Approaches: The Work of KPDV in Postcolonial Africa’, ABE Journal (2013) no. 4, 1-28. http://dev.abejournal.eu/index.php?id=650, accessed 8 November 2014.

-

16Ibid.

-

17Écochard’s main assignment in Senegal was to develop a new master plan for Dakar, however he also studied various other Senegalese cities including Saint-Louis, Ziguinchor, Kaolak, Diourbel, Louga and Thies. By developing these minor cities he hoped to slow down the urban migration to the capital Dakar.

-

18See also Michel Écochard, Le Problème Des Plans Directeurs D’urbanisme Au Sénégal: Documents Présentés Au Conseil National De L’urbanisme, Dakar, Le 7 Octobre 1963 (Dakar: Secretariat d’Etat au plan et au développement, Aménagement du territoire, 1963).

Source: © United Nations, Dag Hammarskjöld Library, New York, NY

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard (photographer)

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard (photographer)

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard (photographer)

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard (photographer)

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard (photographer)

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard (photographer)

Source: © Cité de l’architecture et du patrimoine, Paris. Centre d’archives d’architecture du XXe siècle

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard (photographer)

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

Source: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Michel Écochard

- 1 United Nations Urbanism

- 2 The Emergence of a New Expert

- 3 Redefining Universalism: The Case of Karachi (1953-1955)

- 4 Affording the City: Fria New Town (Guinea, 1956-1958)

- 5 Contesting Spatial Logics: Dakar Development Plan (Senegal, 1963-1967)

- 6 New Roles, Methods and Approaches for Affordable Housing

-

1This research on the United Nations and the HTCP was undertaken together with Maristella Casciato. An introduction to the various activities of the Housing and Town and Country Planning can be found in the various issues of the periodical Housing and Town and Country Planning (New York: United Nations. Dept. of Social Affairs, 1948).

-

2Adequate housing was recognized as part of the right to an adequate standard of living in the Universal Declaration of Human Rights, which was approved by the United Nations General Assembly in 1948 and of which article 25 states: ‘Everyone has the right to a standard of living adequate for the health and wellbeing of himself and of his family, including food, clothing, housing . . .’ It was confirmed in the 1966 International Covenant on Economic, Social and Cultural Rights.

-

3Weissmann emigrated to the USA in 1938 and worked, among others, with Catalan architect Josep Lluís Sert, first on the publication of the book Can Our Cities Survive? (1942), followed by wide-ranging urban studies. Weissmann was crucial in linking local practice and regionalism to the European architectural avant-garde. At the HTCP section, his nationality was an asset: Yugoslavia, although a communist state, followed the path of non-alignment. This neutrality helped allay suspicions among leaders in the developing world that UN planners were simply pawns of one of the two centres of power. It also made it easier for planners on both sides of the Iron Curtain to participate in UN ventures.

-

4The list of contributors to the Housing and Town and Country Planning (HTCP) division is the testimony of this wide range of organizations that were involved. The pages of the periodical Housing and Town and Country Planning illustrate this broad variety of actors and present articles by first generation modernists such as J.J.P. Oud and Walter Gropius, and at the same time represent viewpoints by planners like Jacob Crane and Jacqueline Tyrwhitt.

-

5In its beginning years the bulletin was titled Housing and Town and Country Planning to evolve after 1953 to Housing and Building and Planning. See: Housing and Town and Country Planning (Lake Success, NY: Dept. of Social Affairs, 1948-1953). A catalogue of more than 400 movie titles illustrates the large film holding of the HTCP section, Housing, Building, Planning: An International Film Catalogue (New York: United Nations, Dept. of Economic and Social Affairs, 1956).

-

6See also M. Ijlal Muzaffar, The Periphery Within: Modern Architecture and the Making of the Third World, PhD Thesis (Cambridge, MA: Massachusetts Institute of Technology, Dept. of Architecture, 2007).

-

7The United Nations played a prominent role in this new regime. Together with other, often national, actors such as Poland’s Myastto project (a national planning and development organization) development cooperation). See also the theme issue of The Journal of Architecture: Lukasz Stanek and Tom Avermaete (eds.), ‘Cold War Transfer: Architecture and Planning from Socialist Countries in the “Third World”’, The Journal of Architecture, vol. 17 (2012) no. 3.

-

8Otto Koenigsberger, ‘The Problem Facing the Planner in the Tropics’, unpublished lecture given to the Conference on Tropical Architecture, March 1953, 4.

-

9Architects had always been crossing borders, working occasionally in other countries and cultures. However, in the post-war period there seems to be a kind of architect and urban planner emerging who works permanently across borders. Architects and urban planners, like Constantinos Doxiadis, Michel Écochard, Jacqueline Tyrwhitt, Victor Bodiansky, Jacob Crane and Otto Koenigsberger – to name a few well-known examples – developed a ‘global practice’.

-

10Michel Écochard, Refugee Problems in Relation to Town Planning in Karachi (New York: United Nations, 1955), 9.

-

11Ibid, 10.

-

12For a further exploration of the survey in the work of Écochard see: Avermaete and Casciato, Casablanca Chandigarh, op. cit. (note 8).

-

13Lefebvre, Henri, Le Droit À La Ville (Paris: Anthropos, 1968).

-

14Atelier LWD was an architecture studio led by Guy Lagneau, Jean Dimitrijevic and Michel Weill that was active from 1952 to 1985. For an introduction see: Joseph Abram, ‘Le rêve du réel. Guy Lagneau, Michel Weill, Jean Dimitrijevic, Jean Prouvé et Charlotte Perriand: de la Maison du Sahara aux écoles du Cameroun’, Faces (Geneva), no. 37, 1995, 48-54.

-

15For an extensive introduction to this office see Kim de Raedt, ‘Shifting Conditions, Frameworks and Approaches: The Work of KPDV in Postcolonial Africa’, ABE Journal (2013) no. 4, 1-28. http://dev.abejournal.eu/index.php?id=650, accessed 8 November 2014.

-

16Ibid.

-

17Écochard’s main assignment in Senegal was to develop a new master plan for Dakar, however he also studied various other Senegalese cities including Saint-Louis, Ziguinchor, Kaolak, Diourbel, Louga and Thies. By developing these minor cities he hoped to slow down the urban migration to the capital Dakar.

-

18See also Michel Écochard, Le Problème Des Plans Directeurs D’urbanisme Au Sénégal: Documents Présentés Au Conseil National De L’urbanisme, Dakar, Le 7 Octobre 1963 (Dakar: Secretariat d’Etat au plan et au développement, Aménagement du territoire, 1963).