- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijns

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Marja Elsinga

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Marietta Haffner

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Henk Jonkers

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Self-built

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Chiara Tobia

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Afua Wilcox

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

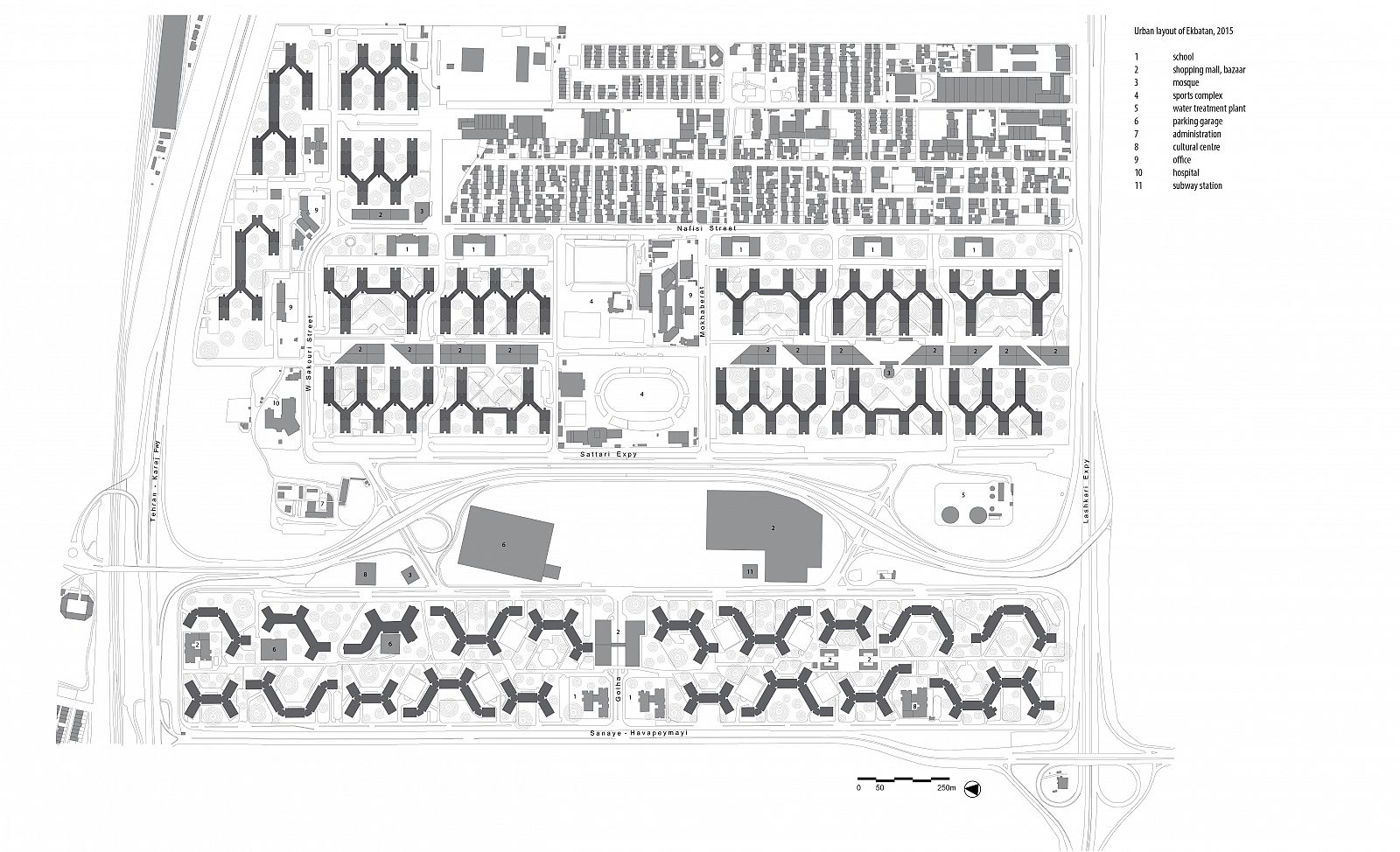

Ekbatan

During the 1960s and 1970s, the close economic ties between the USA and Iran encouraged many American firms to develop various mega-projects in Iran. In 1966, the Iranian Ministry of Housing asked Victor Gruen to prepare a comprehensive master plan for Tehran in collaboration with his Iranian partner Abdolaziz Farmanfarmaian. Gruen’s urban theory, entitled The Heart of our Cities, is based on a hierarchy of urban structures in which the commercial centres have priority. He envisaged the metropolis of tomorrow as a central city surrounded by ten additional cities, each with its own centre. This resembled Ebenezer Howard’s Social Cities, in which a central city was surrounded by a cluster of garden cities. These ideas inspired Gruen to expand the border of Tehran and plan many new suburban residential districts. As a result of his planning, in 1968 a pilot project known as Ekbatan was commissioned by the Tehran Redevelopment Corporative Company on the west side of Tehran. Rahman Golzar and Jordan Gruzen of the American office Gruzen & Partners were asked to collaborate with Victor Gruen to design the biggest residential complex in the Middle East at the time: 15,500 housing units for about 70,000 inhabitants in an area of 221 ha.

The goal of the project was to create the most modern housing project in Iran, to fulfil the Shah’s wishes to push the country towards a modern lifestyle based on Western urban planning elements, residential design and construction technologies. Simultaneously, the project was meant to control Tehran’s population patterns, to accommodate some governmental employees and to reinforce the army by providing affordable housing for its staff and their families. The construction of Ekbatan began in 1970 and the first phase was completed in 1978. Although the Islamic revolution of 1979 caused a short break in the construction process, the implementation of the second phase was continued in 1980, and finally the third phase was completed in 1992.

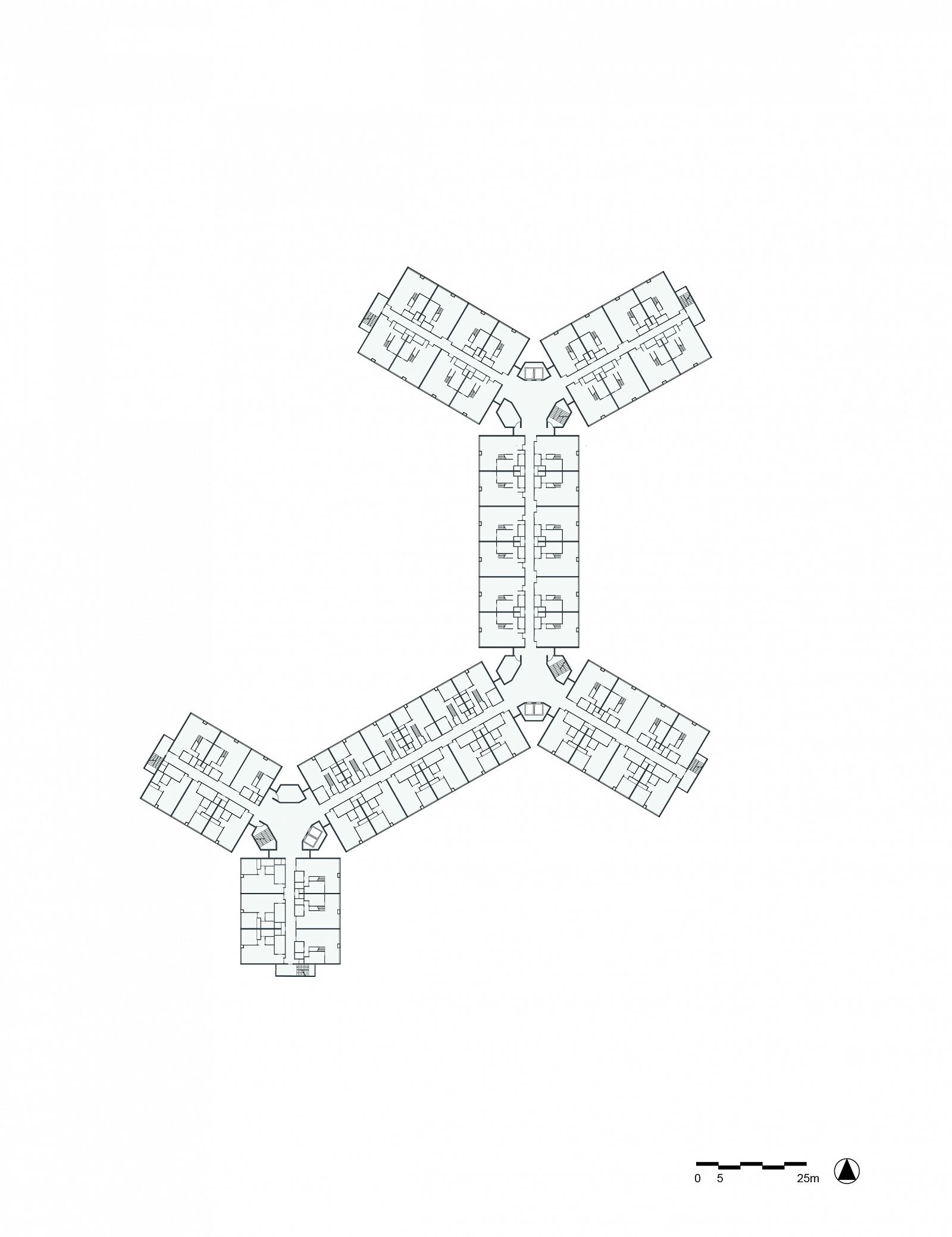

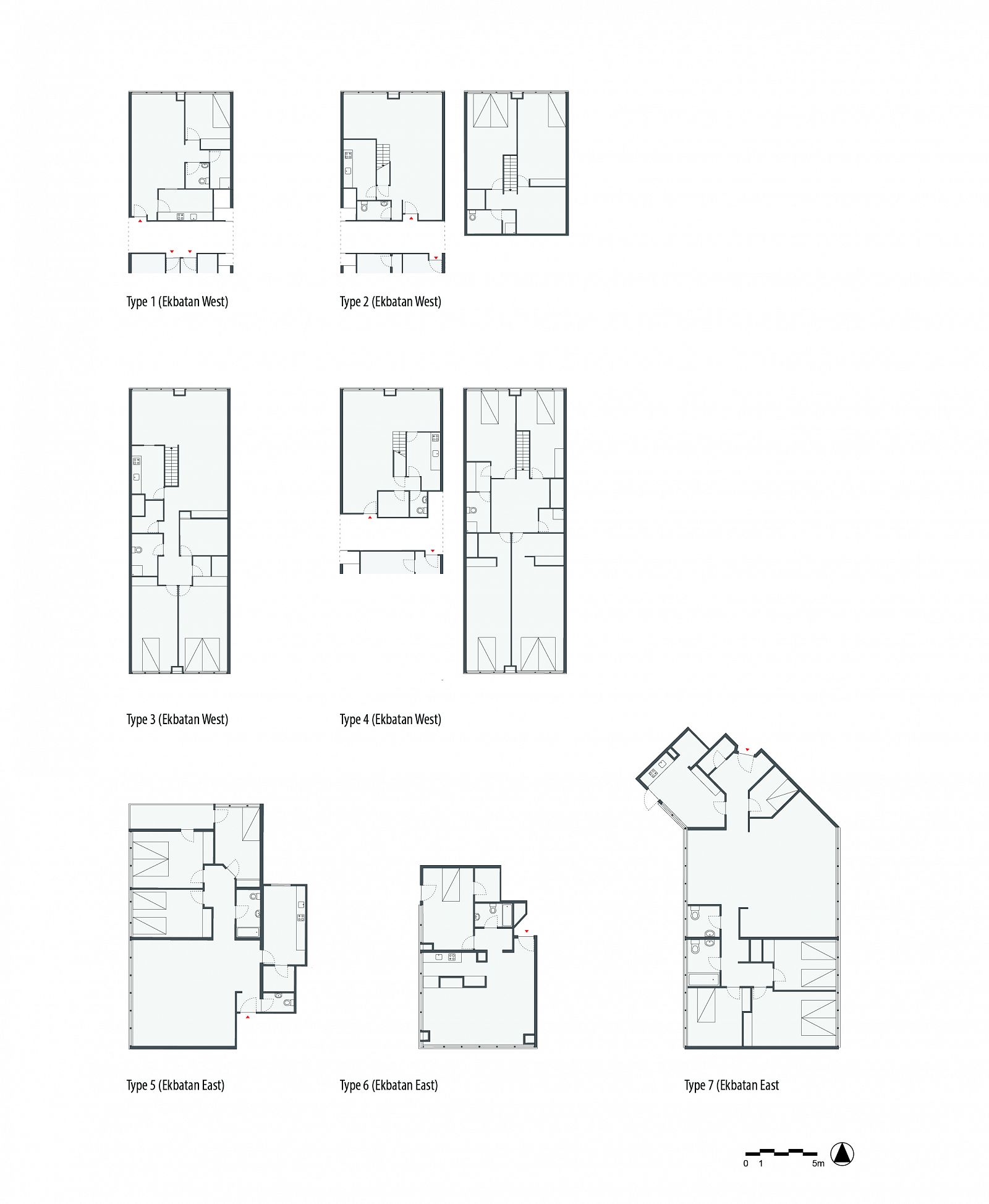

Architecturally, the main point of inspiration for this project was the Unité d’Habitation designed by Le Corbusier in Marseilles. The design consists of 33 huge concrete blocks, for which prefabricated façade panels were used in order to meet the project’s aggressive construction schedule and to create mass production of high-quality and modular housing. A motorway divides the project into two parts, of which the eastern part, containing ten regular U-shaped blocks and four long U-shaped blocks, was intended for usual governmental employees and army staff. The western side of the project, including 19 semi-hexagonal blocks, was meant for high-ranking government employees and members of the middle-class. Each U-shaped block has a three-stepped appearance, with five, nine and then 12 floors, and is raised on columns above the ground to provide a continuous landscape. The semi-hexagonal blocks, however, were constructed as freestanding objects set directly on the ground. Situated in a large green strip, the blocks have an outward uniform appearance of 12 floors, but the internal organization is unique, due to the use of various maisonette types. The series of concrete flats sit starkly in an open space and dramatically ignore the traditions of Iranian housing. In the original plan, green zones and pools were projected in the spaces between the semi-hexagonal blocks, but after the Islamic revolution these luxurious elements were not completely realized. However, a commercial area was added to Ekbatan as a new type of urban public space, which was the most remarkable influence of Gruen on this project. Although this prototype of mass housing is rooted in an ideology of modern architecture totally different from Iranian traditional architecture, Ekbatan is surprisingly considered as a successful housing project by many scholars and as a During the 1960s and 1970s, the close economic ties between the USA and Iran encouraged many American firms to develop various mega-projects in Iran. In 1966, the Iranian Ministry of Housing asked Victor Gruen to prepare a comprehensive master plan for Tehran in collaboration with his Iranian partner Abdolaziz Farmanfarmaian. Gruen’s urban theory, entitled The Heart of our Cities, is based on a hierarchy of urban structures in which the commercial centres have priority. He envisaged the metropolis of tomorrow as a central city surrounded by ten additional cities, each with its own centre. This resembled Ebenezer Howard’s Social Cities, in which a central city was surrounded by a cluster of garden cities. These ideas inspired Gruen to expand the border of Tehran and plan many new suburban residential districts. As a result of his planning, in 1968 a pilot project known as Ekbatan was commissioned by the Tehran Redevelopment Corporative Company on the west side of Tehran. Rahman Golzar and Jordan Gruzen of the American office Gruzen & Partners were asked to collaborate with Victor Gruen to design the biggest residential complex in the Middle East at the time: 15,500 housing units for about 70,000 inhabitants in an area of 221 ha. The goal of the project was to create the most modern housing project in Iran, to fulfil the Shah’s wishes to push the country towards a modern lifestyle based on Western urban planning elements, residential design and construction technologies. Simultaneously, the project was meant to control Tehran’s population patterns, to accommodate some governmental employees and to reinforce the army by providing affordable housing for its staff and their families. The construction of Ekbatan began in 1970 and the first phase was completed in 1978. Although the Islamic revolution of 1979 caused a short break in the construction process, the implementation of the second phase was continued in 1980, and finally the third phase was completed in 1992. Architecturally, the main point of inspiration for this project was the Unité d’Habitation designed by Le Corbusier in Marseilles. The design consists of 33 huge concrete blocks, for which prefabricated façade panels were used in order to meet the project’s aggressive construction schedule and to create mass production of high-quality and modular housing. A motorway divides the project into two parts, of which the eastern part, containing ten regular U-shaped blocks and four long U-shaped blocks, was intended for usual governmental employees and army staff. The western side of the project, including 19 semi-hexagonal blocks, was meant for high-ranking government employees and members of the middle-class. Each U-shaped block has a three-stepped appearance, with five, nine and then 12 floors, and is raised on columns above the ground to provide a continuous landscape. The semi-hexagonal blocks, however, were constructed as freestanding objects set directly on the ground. Situated in a large green strip, the blocks have an outward uniform appearance of 12 floors, but the internal organization is unique, due to the use of various maisonette types.

The series of concrete flats sit starkly in an open space and dramatically ignore the traditions of Iranian housing. In the original plan, green zones and pools were projected in the spaces between the semi-hexagonal blocks, but after the Islamic revolution these luxurious elements were not completely realized. However, a commercial area was added to Ekbatan as a new type of urban public space, which was the most remarkable influence of Gruen on this project.

Although this prototype of mass housing is rooted in an ideology of modern architecture totally different from Iranian traditional architecture, Ekbatan is surprisingly considered as a successful housing project by many scholars and as a

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Source: Archive of Ekbatan Renovation and Development Company

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Source: Archive of Ekbatan Renovation and Development Company

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi