- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijns

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Marja Elsinga

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Marietta Haffner

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Henk Jonkers

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Chiara Tobia

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Afua Wilcox

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

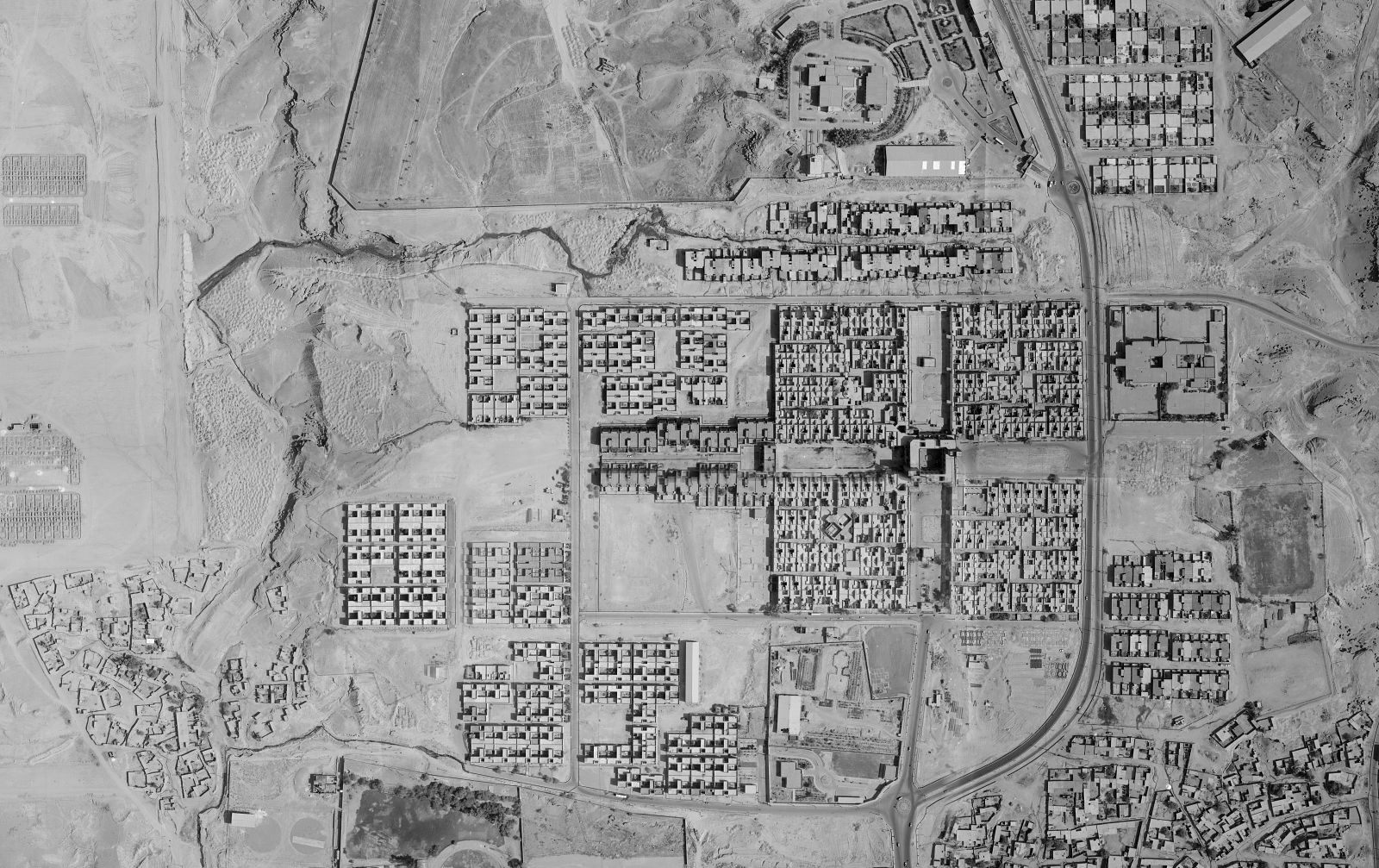

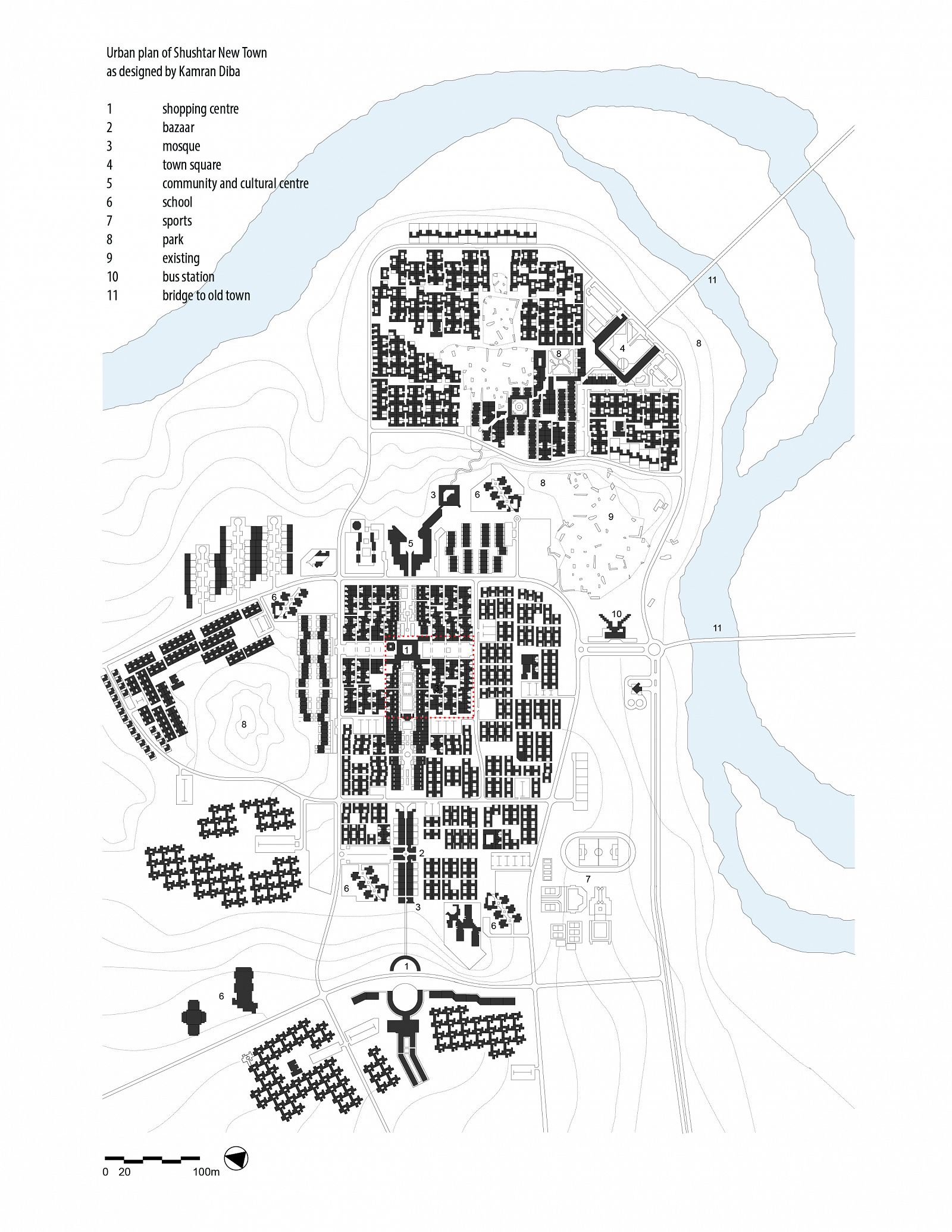

Shustar New Town

Shushtar New Town is one of the most well-known housing projects in contemporary Iranian architecture. Located close to the ancient city of Shushtar in the southwest of Iran, Shushtar New Town follows the traditional urban pattern of Iranian cities with an interwoven urban fabric and (mud)brick as construction material. The project was designed by Kamran Diba in 1972 and planned in five stages, to be completed in 1985. Construction started in 1976 and most of the first phase, which was planned to function as an autonomous unit and to accommodate about 4,200 inhabitants, was completed in 1978. While Shustar New Town was intended to house 30,000 workers of the Karun Agro Industry (major sugar cane and production industry), due to the Islamic revolution of 1979 the project was not completely implemented and only another small part of it was constructed between 1980 and 1985.

On account of the sudden increase in oil revenues in the 1970s, the Iranian Ministry of Housing stimulated different organizations to provide housing for their employees. To achieve this goal, industrial construction systems were taken into consideration. This trend was welcomed by the Western-oriented architects at that time, although this notion neglected local materials and labours, imposed a different lifestyle and ignored the inhabitants’ cultural and social particularities. With the assignment for designing Shustar New Town, Diba took the opportunity to resist these modern concepts and designed a regionally-inspired housing scheme.

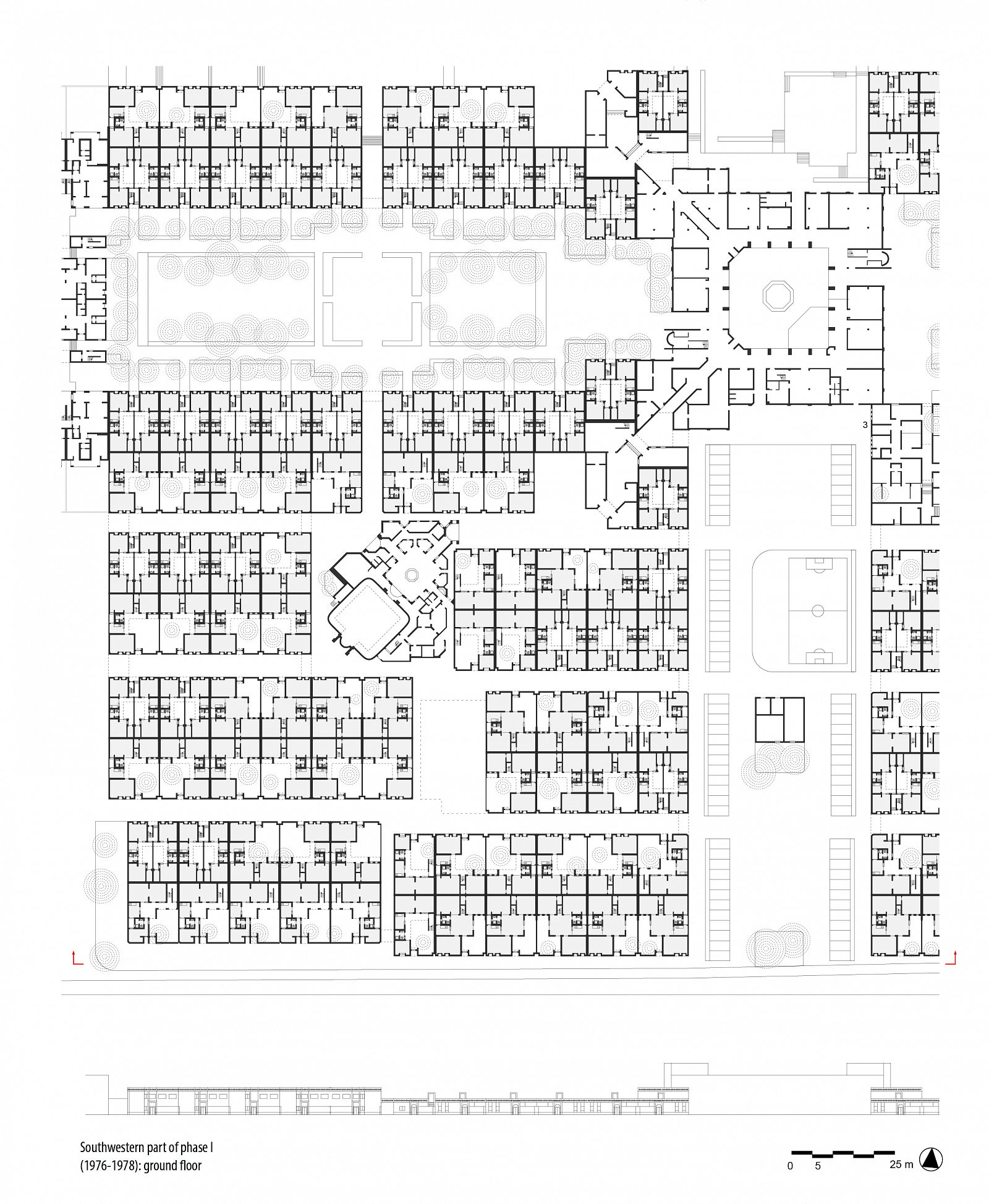

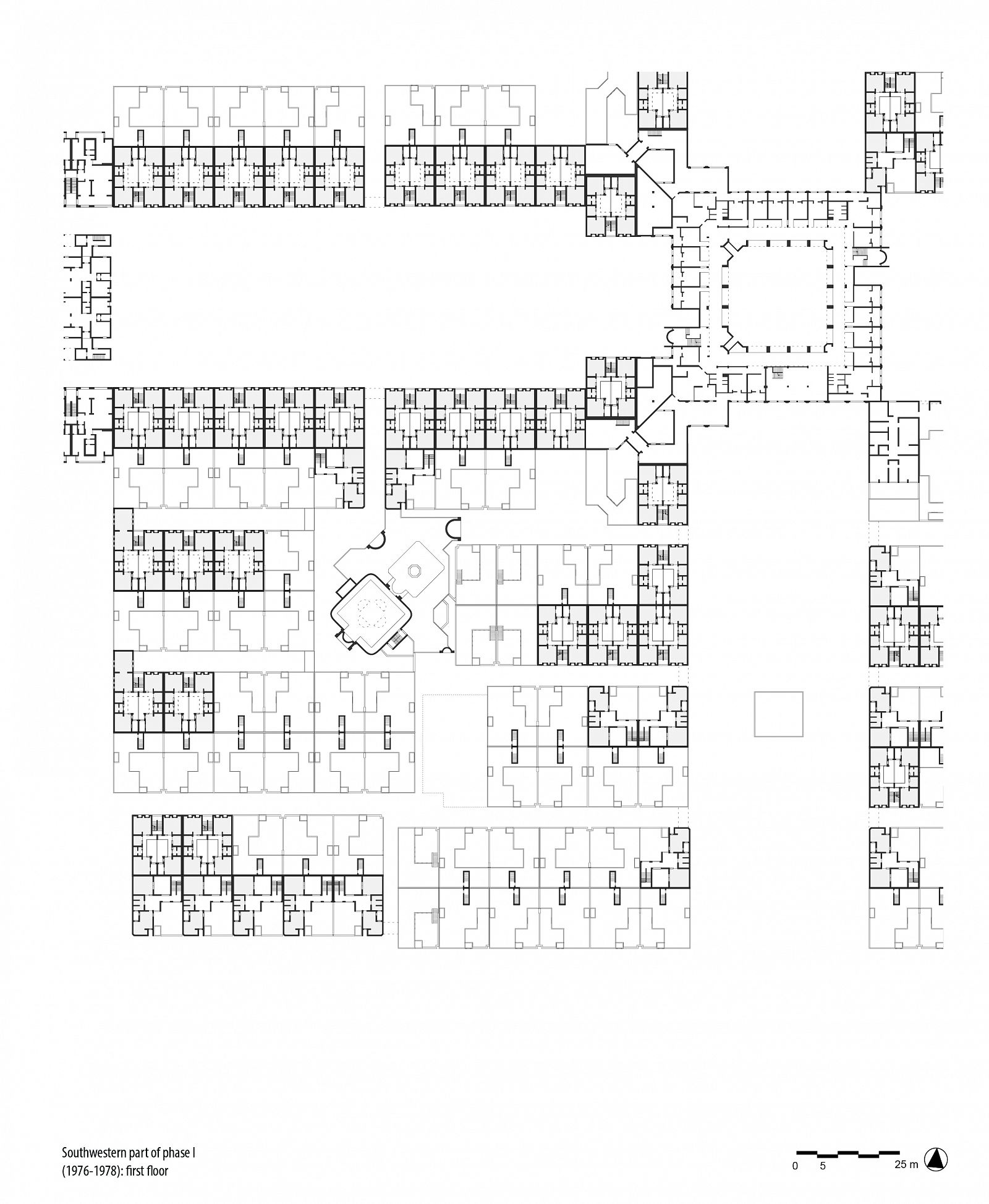

He instigated a quest to provide urban enclaves that address the very cultural and social identity of society. Diba perceives a built city-structure as a ‘social event’ that can multiply and enhance the quality of interaction between people. As a result, in the urban plan he designed a ‘social spine’ consisting of a series of public spaces: paved squares, lush gardens, covered and shaded resting places, fountains and running water, which are lined with schools and bazaars to stimulate socialization. The main plaza – never realized – was to be situated on the riverbank, where a pedestrian bridge would connect the new and the old city. Public space is also provided by the neighbourhood plaza, which connects the four living quarters and is surrounded by shops and teahouses. A neighbourhood mosque in the middle of one of the residential quarters follows the traditional pattern in terms of its integration with the surroundings. A more private sense of public space is created in front of the dwellings, where the houses meet the street. This realm was to be the border between private and public and can be seen as an extension of the dwelling, where children play and parents chat.

For Diba, high-rise building is incompatible with creating a humane community. Moreover he believes that the cultural particularity of Muslim societies resists this kind of unfamiliar dwelling, and that architects should create horizontal density. Based on these arguments, he used a low-rise housing model, in which the majority of the dwellings are one or two storeys high. Contrary to the Western notion of the house as an agglomeration of different rooms with particular functions (living room, dining room, bedroom), the traditional concept of the room as a polyvalent space was his departure point. In conceptualizing the dwelling units, the courtyard, which architecturally represents the cultural identity of Iranians, was the main source of inspiration for designing. As a result, the courtyard was placed at the heart of the dwelling and the rooms were attached to it. Most rooms in the two- to four-room houses are 5 x 5 m; smaller ones are 3 x 3 or 4 x 4 m. The roofs of the residential buildings are connected, creating an upper-level cityscape based on the traditional roofscape of Iranian cities.

To build the project, traditional construction methods, local materials and mostly local, unskilled labour were used. Shustar New Town is a unique example of a large-scale urban development conceived and produced by local designers and builders with respect for indigenous lifestyles.

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Aga Khan Trust for Culture / Bijan Zohdi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi

Photo: © Mohamad Ali Sedighi