- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijn

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

Cross-Pollination in the Doshi Habitat

A Report from Ahmedabad

Students of Delft University of Technology have been taking part in the Habitat Design Studio in Ahmedabad since 2010. The design studio is organized annually by Balkrishna Doshi and his firm Vastu Shilpa.1 For two months, the students work on a task related to the explosive growth of the city together with other European students and students from India. This may involve slum improvement, urban densification challenges or design research with regard to self-build practices. For the 2015 edition, the construction of a new subway line was reason to investigate its possible effects on the existing urban tissue. All studio editions centred on local neighbourhood communities and how these can be best enabled to reshape their own living environment. The students live in Ahmedabad for two months and their work at Doshi’s firm immerses them in the culture of India, the context of rapid urbanization and the conflicts arising between twenty-first-century modernity, growing new middle classes that embrace a materialistic lifestyle, and the influx of migrants who try their luck in the city while still holding on to a much more traditional lifestyle.

Learning from Ahmedabad

The following is an impression of three visits to Ahmedabad and Doshi’s studio. While these were short and therefore rather superficial visits, they did leave an impression of the situation and of the importance of the studio with regard to the students and their training as architects as well as to the role that architecture as a design discipline can play in the rapid urbanization in large parts of the world, without being reduced to merely the process management of social practices. I believe cross-pollination is the key concept at all levels, between the cultures of the East and the West, Europe and India; between the disciplines of architecture, planning and sociology; between the universities involved and among the students. For the Delft students already bring cultural baggage from all over the world with them, they are not a homogenous group: so far, participating Delft students have been from the Netherlands Spain, Germany, Norway, Italy, France and Ireland, and from non- European countries such as Iraq, Japan, Taiwan and South-Africa.

‘Cross-pollination’ also fits Ahmedabad as a historical trading centre. Ahmedabad was among the ports of call of the Dutch East India Company, as the ancient Dutch cemetery, built around 1700 on the banks of Lake Kankaria, modestly witnesses. Once there was even a factory and a city guide mentions fierce competition between the English and the Dutch about the control of the Ahmedabad textile industry in the beginning of the eighteenth century.2 To the tuk-tuk driver who picks you up in front of your hotel, the cemetery is known as a ‘heritage’ destination. For about 70 rupees per hour, he will drive you around his city. The best place for any outsider to experience the Indian city of Ahmedabad is probably from the back seat of a tuk-tuk. Somewhat protected by the yellow roof of the rickshaw, you will watch an urban cityscape go by that is both dilapidated and bursting with energy. While you succumb to the heat, diesel fumes and sonorous engine sound, you will undergo a motley succession of impressions of urban life, market stalls and eateries, slum enclaves, shopping malls, modernist apartment buildings, the odd quiet, exclusive residential neighbourhood, neglected pieces of farmland closed in by new districts, offices, factory sites, educational institutions and many, many temples.

The street is the place of choice for cross-pollination and exchange. For trade, first of all. Sometimes it seems as though you are driving through an open-air department store, with pavements and roadsides completely covered in displayed merchandise. You can get your hair cut or have a cup of chai. Every once in a while you will end up in a procession, an involuntary participant of a religious spectacle. The streets are also ideal places to hang out, though not for everyone. There are unwritten rules. I once made the mistake – being a European – of sitting down on the pavement, just to watch all the traffic. I promptly became the centre of a crowd: Was I all right? Shouldn’t I go inside, where there was air conditioning? Sitting and hanging out in the streets is for the poor: for street traders, for boys with motorbikes and tuk-tuk drivers. The middle classes and the rich prefer an ordered private world that is cooled by air conditioning and cleaned by staff sweeping gardens and rooms. After all, besides hot and crowded the streets are also dirty: unclean. The amount of waste and plastic along the side of the road is simply overwhelming for someone from the well-ordered Netherlands.

Large billboards promoting a radiantly new lifestyle in equally radiant new residential buildings are suspended over the dirty, dusty streets. Real estate development is big business. Thanks to the country’s explosive economic growth, for many people a better standard of living is within reach. At the same time, large groups are left behind. Despite ambitious government campaigns to let residents of slums and informal settlements share in the new prosperity, tens of millions of people still live in poverty on the Indian subcontinent. Depending on which report you read, 10 to 30 per cent of the population lives in slums, which in the cities might well mean more than half of the population. Owing to the continued influx of new migrants, the cities’ problems are rapidly increasing. Finding good housing also presents a big problem to the lower-middle classes. Though its urban conditions are not as extreme as those of Mumbai or New Delhi, Ahmedabad is one of the fastest-growing cities in India. Population figures now range from 5 to 7 million. It makes the ancient city the perfect place to study the sociocultural transformations taking place in India.

I do not want to portray the Indian context as something exotic that the Western visitor cannot be part of, yet find it hard to avoid the impression that in India, modernity and modernization have developed along different lines than in Europe.3 The parts culture and history play cannot be neglected. Religion is a major social and political factor. And class differences, ethnicity, gender roles and sexuality are linked to social values that dictate the use of public and private space. This may seem too self-evident to even mention but surprisingly, these factors are hardly mentioned in the numerous architectural studies about the advent of megacities. They become casualties of a bulk of abstract data and all too often dissolve in the global perspective of an international avantgarde of experts. Paradoxically, despite all good intentions, focus on participatory models, user-driven planning and bottom-up ideologies, what appears in the discourse about informal urban development is an anonymous lumpen proletariat. It is an unintended side effect of the debate on global cities that started with Ricky Burdett and the Venice Biennale of 2006, which was devoted to ‘the limitless urban growth’.4

Presenting six design scenario’s for the possible solution of the problems surrounding the informal urbanization of six megacities, the exhibition ‘Uneven Growth’ at the MoMA in New York (2014) addressed this impossible paradox yet at the same time found it hard to escape.5 The multidisciplinary teams made up for the occasion contained a mix of outsiders and local stakeholders who could not rid themselves of a global perspective. The ‘Uneven Growth’ argument included different scenarios that aimed to provide alternatives for current urbanization practices. Using a kind of ‘tactical urban development’, as defined by the designers, the contemporary proletariat was supposed to throw off the miserable circumstances of the slums in which it had to live. Local communities were considered strongholds of democracy, whereas the new middle classes had to liberate themselves from imposed consumption patterns. To counterbalance the high finance elite and the failing central government, solutions were found outside politics, in alternative organizational forms of governance, like cooperations and commons. Architectural design became process management and the role of architects was described as that of social workers – as happened in the 1970s.6

Even architecture as an autonomous discipline was considered suspect, as it is easily associated with the ruling classes that are held responsible for the misery in the megacities. This raises questions as to what it is that architects might contribute besides a form of ‘smart social engineering’. This question is also pivotal at the Habitat Design Studio in Ahmedabad.

Ahmedabad in a Nutshell

For those who do not know Ahmedabad: it is located about 500 km north of Mumbai in the federal state Gujarat, which borders Pakistan and is known for its textile and cotton industry. This is why the city was also known as ‘the Manchester of India’. It was here that Ghandi settled in 1915 to fight his nonviolent war against the British former colonial power, religious conflicts and the exploitation of the lower classes, including the textile workers and the untouchables. This is why there is a Gandhi museum in Ahmedabad, the Sabarmati Ashram, which consists of Ghandi’s original living quarters and a modest museum pavilion, an early design by Charles Correa (1958-1963). The people of Gujarat are mostly Hindus and meat and alcoholic beverages are prohibited in principle, though they are on offer at some of the venues that mainly cater to foreigners. India’s current Prime Minister, Narendra Modi, is from Gujarat and tends to spread the Hindu message rather emphatically, to the dismay of the Muslim community in particular. Only in 2002, tensions between Hindus and Muslims led to the death of hundreds of people in Gujarat. Ahmedabad also houses a Muslim minority and there are several ancient mosques in the city. Other spectacular historical heritage sites that are closely connected to the alternating rule of Hindus and Muslims include the step wells, low-lying springs that are sometimes dozens of metres below ground surface, accessible by richly ornamented stairs, like the well at Adalaj. North of Ahmedabad lays the famous sun temple and water tank at Modhera, which with its elementary and sculptural stairs has been a source of inspiration to structuralist architects like Correa, but also Herman Hertzberger.

Though decrepit, the ancient town centre is largely intact and includes various examples of historical residences, the haveli, which feature refined wood carvings. The haveli were once the homes of the rich upper classes, but neither the upper nor the lower-middle classes live in the town centre these days. Not only are the houses in bad condition, necessities such as water are in limited supply and residents often have to make do with roadside taps. Vacant houses are occupied by new migrants. The ancient town centre is an intricate web of clusters of so-called pols, narrow streets and alleys that were once closed at night for safety purposes. A pol was a social unit that more or less coincided with the social structure of families and castes. Ancient Ahmedabad consisted of hundreds of such ‘gated communities’. Just like the hutong in China, the kampong in Malaysia and Indonesia and the souk and kasba in Arab countries, pol is an urban concept unfamiliar to Europeans. Tourists easily lose their way here, there are no city maps available: only the central shopping streets, temples and markets help you find your way through this labyrinth.

Public space in Ahmedabad is a completely new challenge. The streets of Ahmedabad are neither designed nor intended as public space: residents and users appropriate them as places to meet and make exchanges. In the context and from the perspective of local communities, public space is a totally different kind of meeting space than the public space in contemporary European cities, or the public space in global cities, which emerges in connection with dominant international networks. As yet, Ahmedabad Airport is very modest in size. An international terminal opened in 2010. Now that Ahmedabad is gearing up to become a player in the global cities’ network, the issue needs addressing. This is apparent, for instance, from the large-scale boulevard project of concrete quays and retaining walls along the banks of the Sabarmati River, a project that is being criticized for its slapdash approach in terms of water management and unsuccessful land speculation.

Despite the influx of migrants from the countryside, this city with over 5 million inhabitants feels relatively liveable and compact, with mostly low-rise and medium-rise buildings. Though busy, the traffic is not completely dominated by cars (yet) but rather by tuk-tuks, bicycles and motorcycles. During the morning and evening rush hours there are traffic jams at major crossroads, which result in horn-blowing concertos that last for hours. Half-ironically smiling locals warn that crossing a major road here is nothing short of a leap of faith. All clichés are (thankfully) confirmed: traffic lights are ignored, cows and dogs are common, picturesque parts of the streetscape and every once in a while, you come across an elephant or a camel.

In the context of post-war modern architecture, the city can be called an exceptionally cross-pollinated place. Balkrishna Doshi is the embodiment of this cross-pollination. Architects worldwide are aware of Ahmedabad because of a handful of highlights: the Mill Owners Association headquarters(1954-1956), which like Villa Shodhan (1951-1956) and Villa Sarabhai (1951-1955) was designed by Le Corbusier. Louis Kahn and his associate Anant Raje built the monumental campus of the prestigious Indian Institute of Management (1962-1974). Doshi, now 87 years old, was closely involved in the realization of these masterpieces at the time. He worked at Le Corbusier’s Paris office from 1951 to 1954. Le Corbusier’s project in Chandigarh in the north of India led to several commissions by the wealthy textile barons of Ahmedabad, like the Sarabhai family. To realize these Ahmedabad commissions in particular, Doshi left Paris for India to launch his own firm. This not only marks the start of a highly productive career in architecture: in 1962, Doshi also started his own school of architecture in Ahmedabad, the CEPT (Centre for Environmental Planning and Technology), for which he also designed the campus buildings, a first phase in 1966-1968 and a second phase in 1975-1977. In addition, Doshi designed several houses and housing projects in the city, as well as urban renewal projects, various educational facilities, cultural institutions (including the Gandhi Labour Institute, 1980-1984) and, finally, his own offices (1979-1981), which are, more than any of his other projects, a demonstration of his architectural principles with regard to sustainable living environments and social relations.

The Oasis of Sangath

The offices of Doshi and Vastu Shilpa are in the western part of town. It is not always easy to explain its location to tuk-tuk drivers. The address is on the busy Drive In Road, just past the drive-in cinema, and the complex is also know by the name Sangath, but not all drivers know this. Underway, directions have to be fine-tuned regularly. Finally, you are dropped off on the side of the road near a grey stucco garden wall. Once you have entered through the orange-red gate in the garden wall, a big surprise awaits you. After the noise and the dust of the busy Drive In Road, which takes you from the ancient town centre and over the Sabarmati River to the western periphery of the expanding city, you suddenly find yourself in a green oasis. A garden path with carefully inlaid patterns of recycled ceramic shards takes you by lush greenery and a pond in the direction of a collection of white barrel vaults to one side in the back of the garden. A couple of steps take you down to a shaded porch before you actually enter the building.

You could describe the interior as ‘a bunch of places’, just as Aldo van Eyck intended it. Including views and thresholds, a mini labyrinth of intermediate spaces unfolds that houses the employees of the office, the reception desk, the interview rooms, the double-high drawing and model rooms, to end in Doshi’s own room. The application of materials betrays Doshi’s affinity with Le Corbusier and Louis Kahn: lots of untreated concrete, built-in and fixed furniture, tiles and untreated and treated woodwork. The scale is intimate, almost domestic, and there is a direct physical relationship with the spaces: the walls and partitions, the staircases, tiles and other details like railings and thresholds are all easy to the touch. The eye can already see what they are going to feel like, while the hand is still following the eye to stroke the surface of a wall or desk.

Doshi interprets the Gujarati name ‘Sangath’ as ‘moving together’, sometimes ‘moving together through participation’. The name of the firm also reads like a slogan or agenda for architecture: Vastu Shilpa means ‘design of environment’.7 This betrays a dynamic understanding of space and social practices and an almost holistic approach to architecture, urban planning and housing issues. Like ‘habitat’, it furthermore also shows Doshi’s strong affinity for the Team 10 discourse.8 Like Hertzberger in the Netherlands, he thus represents an extraordinary continuity that connects the 1950s to the twenty-first century. Doshi attended the 1951 CIAM conference in Hoddesdon and met Jaap Bakema, who regularly lectured at the American Washington University in St Louis, in the second half of the 1950s. Other connections include the collaboration with Christopher Alexander, who conducted his doctoral research in India.9 As is well known, Alexander presented his research to Team 10 in Royaumont in 1962, research that would later lead to his famous book Notes on the Synthesis of Form, about context and social relations based among other things on his research into ways of life in Indian villages.10 Doshi also attended the 1966 Team 10 meeting in Urbino organized by Giancarlo De Carlo, at which time he presented one of his projects for an industrial neighbourhood project.11

More than anyone else who attended the Team 10 meetings, Doshi managed to actually incorporate the idea of an ecological habitat, which was the foundation of Team 10 and included as such in the 1954 ‘Statement on Habitat’, the so-called ‘Doorn Manifesto’, in his housing projects.12 In the Indian context, ideas regarding growth and change could not but become a natural part of Doshi’s design strategies to house the lower classes. His work, from his earliest projects for cheap housing in Ahmedabad for ATIRA (Ahmedabad Textile Industry’s Research Association) and PRL (Physical Research Laboratory) in the late 1950s to his famous Aranya project in the 1980s, for which he received the Aga Khan Award, represent a continuous development of simple basic rules that accommodate growth and change generated by the residents themselves. Subdivision and a very simple core including basic sanitary facilities are the most minimal necessities for a development that is completed and enriched by the residents themselves. The neighbourhood literally grows through the development of and investments by the community. Extra rules may involve zoning for the fleshing out and further development of the basic lots or a first cell as a first main space perhaps combined with a kitchen and a private patio beyond. Where housing projects require a greater density, the dwellings are stacked. Collective outside stairs regulate the direct contact with the street. Doshi never included the galleries or raised streets that were once so popular among European Team 10 colleagues in his projects. His are always high-density low-rise developments. The rhythm of the lots, the repetitive basic structure of the access roads, the private and public spaces, the correct connection to the residential paths or roads, the proper positioning of the collective outside stairs: they all contribute to the creation of a cohesive tissue that is open to appropriation and further expansion by the residents. In Ahmedabad, the same principles can be found in Doshi’s housing project for the Life Insurance Corporation (1973-1976), which includes numerous changes and additions made by the residents.

Creating thresholds and zones, filters between the various private and public domains and everything in between, is crucial to make the whole thing work. The structure of the built environment creates a syncopated counter rhythm of daily lifecycles with their own routines and rituals.13 Doshi points out the importance of the ambiguous character of the intermediate spaces that, due to their ambiguity, residents can use in a variety of manners, which makes a richer experience possible. In his words, it is about creating ‘breaks’ that interrupt a one-sided, rational and linear development. In his lecture ‘Give Time a Break’ for the Anytime conference in Ankara in 1998, Doshi says:

Our measure of time is accelerating, and events are now coupled with rapid change and uncertainty. The relationship of man to built form has become transitory, and identity has become synonymous with quick, result oriented action. Symbols are now dependent upon a constantly changing and increasingly uncertain world view. Against this myopic world view and the resulting well-structured, extremely regulated, mechanized architectural spaces, the only constant that can recover our sensibilities is the introduction of the pause, the ‘gap’ or unexpected, ambiguous link. This gap, or ‘open-ended ambiguity’, through its momentary sense of repose in time and re-orientation of space, help counteract stressful activity. In architecture, this gap or pause is the un-assigned loosely superimposed space, the corner or corridor or irregular courtyard accidentally discovered. In these spaces use is undefined and choice is unlimited . . . they contain the possibility of spontaneity.14

Strikingly, rather than to Team 10 or the Western tradition, Doshi’s argument about the architecture of ‘breaks’ and intermediate spaces refers explicitly to traditional Indian architecture:

Traditional Hindu architecture, which expresses through movement – whether fast or slow with several pauses – is perceived not only as part of this instant or eternity, but as an intimate experience. Architecturally, the broken wheel of time is expressed as a sequence of juxtaposed long and short corridors with a variety of pauses, scales, interspersed courtyards, and unexpected visual barriers, including changes in structural expression or in the quality of light . . . One can be transformed through a proactive dialogue with space and time. One can cross a threshold into another space, another time, and another phase of psychological and spiritual experience. Walls, columns, surfaces, rhythms, light, etc., are instruments that activate these spaces.15

Doshi emphatically has the architect play a part in the accommodation of social processes. Architecture can even potentially transform these processes by a proper articulation of spatial conditions by means of the above-mentioned architectural elements. He wields a dynamic understanding of architecture and social relations, with architecture subservient to transformation or even metamorphosis, not in a purely spatial or physical sense but first and foremost in a psychological or even spiritual sense.

Again, the overlap with the Team 10 discourse is huge when you consider that Peter Smithson, for instance, talked about transformation and appropriation of spaces in exactly the same way and that Bakema, referring to French philosopher Henri Bergson, embraced the idea of change as a fundamental principle of a living architecture. Ultimately, the interest of Team 10 and the principles described by Doshi are embodied by the example of the sixteenth-century palace city Fatehpur Sikri. A natural reference for Doshi, it is also a popular example of Van Eyck and among the Dutch Forum group. Alison Smithson in turn included the palace as the conclusion of her canon of so-called ‘matbuildings’, which she believed epitomized the Team 10 philosophy.16 Thus, Doshi’s work raises the question to what extent the philosophy of Team 10 must be considered a specifically European discourse, as suggested by Alison Smithson herself and by others, or whether there is perhaps something else going on here indeed, for instance a process of cross-pollination in which the culture and civilization of a former colony have an extraordinarily profound impact on those of the colonizer.

Habitat Studio

There is yet another reason to place Doshi’s practice in the context of the latter days of the CIAM and of the Team 10 discourse, and that is the format of the Habitat Design Studio. This is in the tradition of the teaching of Team 10 and the post-war CIAM Summer Schools in Venice, bringing students and teachers from different countries and cultures together. Remember, Bakema tirelessly travelled the world giving his multimedia lectures, always teaching seminars and workshops of the same assignment, namely that of the city, like at the Internationale Sommerakademie in Salzburg, where he taught a studio for many years. The Berlage institute, founded by Hertzberger and currently part of Delft University of Technology as an advanced Masters course, is organized along the same lines. Another example is Giancarlo De Carlo’s ILAUD, the International Laboratory of Architecture and Urban Design, which he founded in 1976 and which kept the Team 10 discourse going for 30 years. Peter Smithson, Aldo van Eyck and Herman Hertzberger stayed there and so did Doshi, in 1987 and 1991. These teaching methods generate cross-pollination like no other. Typically, they are outside the curricula of schools of architecture; they are special moments that facilitate reflection and speculation precisely because they are extracurricular. Doshi would say they are a break in the academic discipline, which is precisely why they offer opportunities for crossing boundaries, innovation and enrichment.

-

1For a brief overview, see http://www.vastushilpa.org/international-studio.html. The studio dates back to 2003. Architecture Schools in Australia, Denmark, France and Switzerland have taken part in the Habitat Design Studio. The students are supervised by a multidisciplinary team of teachers. Especially the contribution of prof. em. Neelkanth Chhaya should not go unrecognized.

-

2Paul John and Ashish Vashi, Ahmedabad Next. Towards a World Heritage City, (Ahmedabad: Bennet, Coleman & Co., 2011), 30.

-

3No Western scientist would dare to since Edward Saïd’s postcolonial criticism. However, Indian writer Pankaj Mishra suggests rewriting the history of modernism from a specifically Asian perspective in: Temptations of the West: How to Be Modern in India, Pakistan, Tibet and Beyond (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006) and From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt against the West and the Remaking of Asia (London/New York: Allan Lane, 2012).

-

4See also Ricky Burdett and Deyan Sudjic (eds.), The Endless City (London: Phaidon, 2007).

-

5The exhibition was organized by the MoMA together with the MAK of Vienna and was on show in New York from 22 November 2014 until 10 May 2015. The six cities were Hong Kong, Istanbul, Lagos, Mumbai, New York and Rio de Janeiro. The catalogue was compiled by curator Pedro Gadanho: Uneven Growth. Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2014).

-

6The director of the MAK, Christoph Thun- Hohenstein, says in his foreword: ‘It has become abundantly clear that architects will have to be first and foremost social workers if the profession is to retain its relevance and go beyond the “architecture- as-art” glamour projects that some cities and countries still rely on to impress the world.’, ibid., 9.

-

7Balkrishna Doshi, Paths Uncharted (Ahmedabad: Vastu Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design, 2011, second edition 2012), 166; William J.R. Curtis, Balkrishna Doshi. An Architecture for India (Middletown, NJ: Grantha Corporation/Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 1988, reprinted in 2014), 118-135.

-

8In William Curtis’s book, Doshi’s autobiography includes: ‘1967-1971: Member Team 10’, (174), which is remarkable because there was no official group membership. Alison and Peter Smithson contested the idea that Doshi was a member of the group in an interview with Clelia Tuscano in Max Risselada and Dirk van den Heuvel (eds.), Team 10. In Search of a Utopia of the Present (1953-1981) (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2005), 338-339.

-

9Alexander and Doshi jointly published the text ‘Main Structure Concept’ in Landscape, vol. 13 (1963-1964) no. 2, 17-20, reprinted in: Ekistics, vol. 17 (1964) no. 103, 352-354. According to an address list from 1963 kept in the Jaap Bakema archives in Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, Alexander used Doshi’s address during his stay in India.

-

10Alison Smithson, Team 10 Meetings 1953-1984 (New York: Rizzoli, 1991), 68-69; Christopher Alexander, Notes on the Synthesis of Form (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1964).

-

11Doshi himself mentions the residential area for the Electronic Corporation of India in Hyderabad, but that was built between 1968 and 1971, after the Urbino meeting of 1966. In our Team 10 book we mention the industrial neighbourhood in Baroda for the Gujarat State Fertilisers Corporation, which was built between 1964 and 1969. See Risselada and Van den Heuvel, Team 10, op. cit. (note 8), 140- 143; and Doshi, Paths Uncharted, op. cit. (note 7), 241.

-

12Doshi himself mentions the residential area for the Electronic Corporation of India in Hyderabad, but that was built between 1968 and 1971, after the Urbino meeting of 1966. In our Team 10 book we mention the industrial neighbourhood in Baroda for the Gujarat State Fertilisers Corporation, which was built between 1964 and 1969. See Risselada and Van den Heuvel, Team 10, op. cit. (note 8), 140- 143; and Doshi, Paths Uncharted, op. cit. (note 7), 241.

-

13In his book, William Curtis talks about Doshi’s work in terms of an ‘armature over which the chaos of life would play another pattern’. See Curtis, Balkrishna Doshi, op. cit. (note 7), 82.

-

14Balkrishna Doshi, ‘Give Time a Break’, 12-13, part of the collection box Talks by Balkrishna V. Doshi (Ahmedabad: Vastu Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design, 2012).

-

15Ibid., 6-7.

-

16Alison Smithson, ‘How to Recognize and Read Mat-Building. Mainstream Architecture as It Has Developed towards the Mat-Building’, Architectural Design, 9 (1974) 590; Smithson also included an example from Ahmedabad: the Museum of Knowledge by Le Corbusier (1949-1957); the building currently houses the city museum, 584.

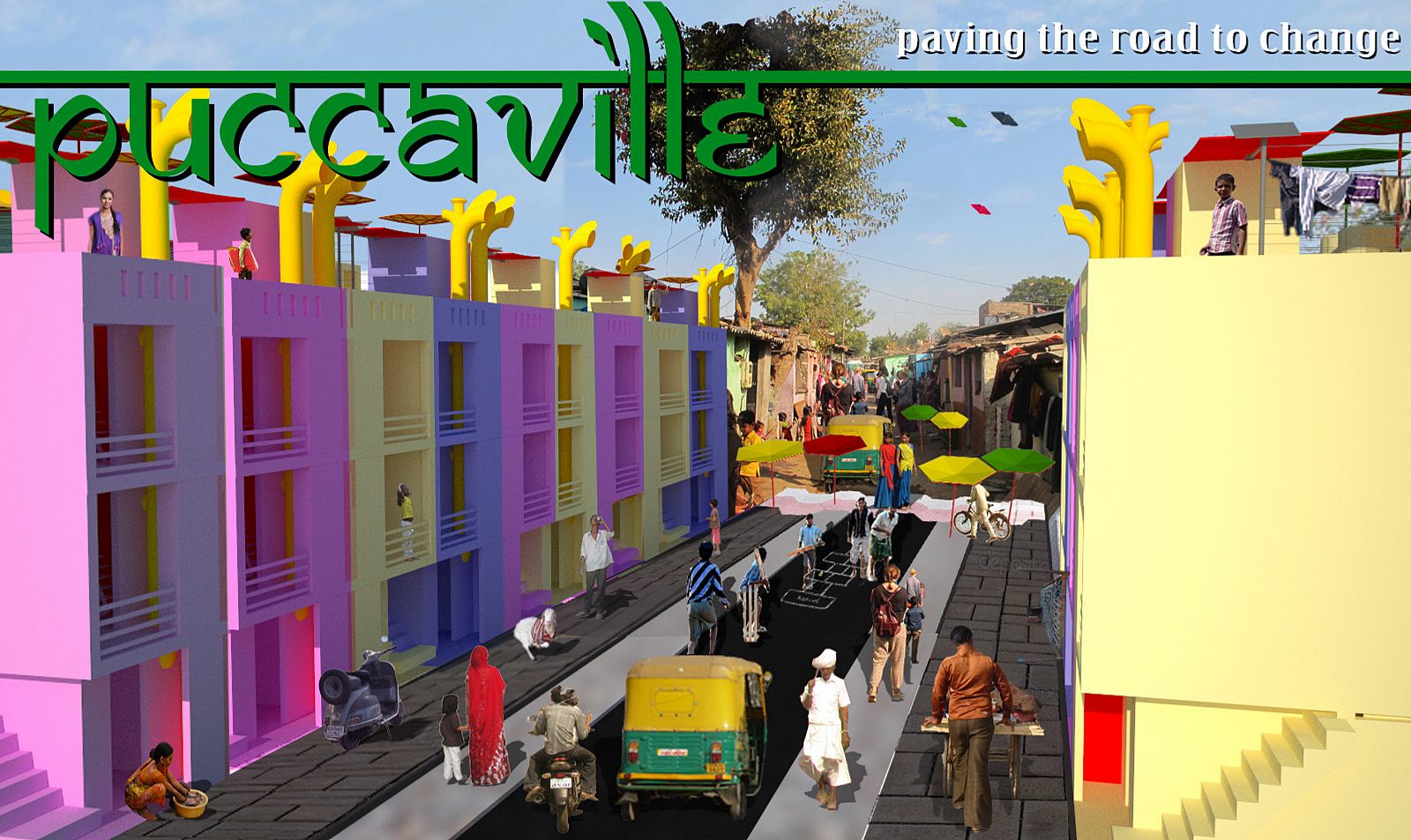

Image: © Kaegh Allen, Gesine Appel, Elena Brunette, Mariel Drego and Blanca Perot

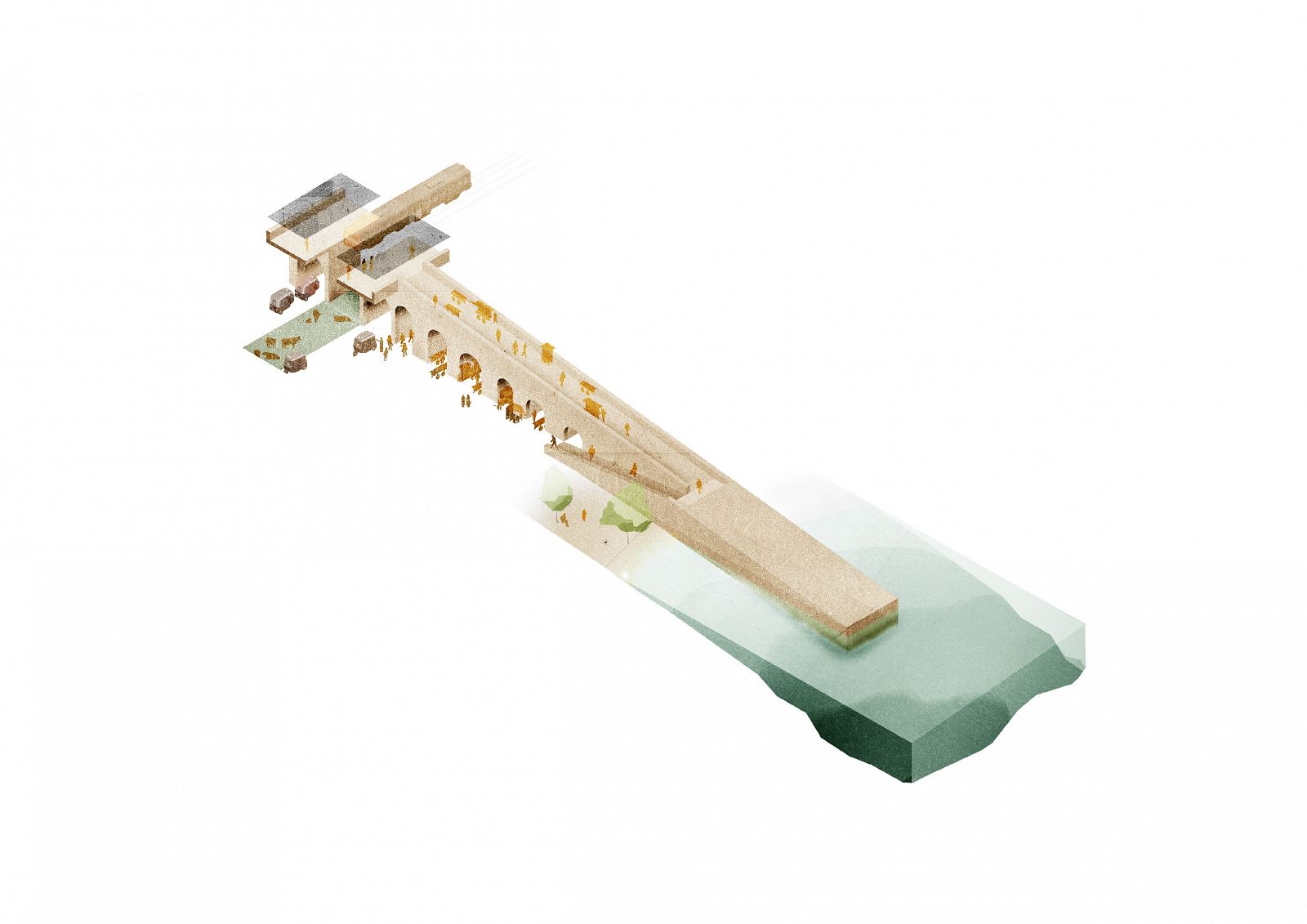

Image: © Morgane Goffin, Ami Gokani, Lex te Loo and Lukas Mahlendorf

Photo: © Dick van Gameren

Photo: © Dirk van den Heuvel

Photo: © Dirk van den Heuvel

Photo: © Dirk van den Heuvel

Photo: © Dirk van den Heuvel

Photo: © Dirk van den Heuvel

Photo: © Dirk van den Heuvel

Photo: © Dirk van den Heuvel

Image: © Ana Barbier Damborena, Nidhi Deshpande, Floor Hoogenboezem, David Meana and Yasuko Tarumi

Image: © Ilse van den Berg, Chalotte Grace, Ameya Joshi, Giorgio Larcher and María Tula García Méndez

Image: © Aidan Conway, Leticia Izquierdo Garcia, Marlene Hamacher and Azul Campos Vivo

Image: © Marlen Beckedal, Rohit Raj, Ellen Rouwendal and Laura Strähle

- 1 Learning from Ahmedabad

- 2 Ahmedabad in a Nutshell

- 3 The Oasis of Sangath

- 4 Habitat Studio

-

1For a brief overview, see http://www.vastushilpa.org/international-studio.html. The studio dates back to 2003. Architecture Schools in Australia, Denmark, France and Switzerland have taken part in the Habitat Design Studio. The students are supervised by a multidisciplinary team of teachers. Especially the contribution of prof. em. Neelkanth Chhaya should not go unrecognized.

-

2Paul John and Ashish Vashi, Ahmedabad Next. Towards a World Heritage City, (Ahmedabad: Bennet, Coleman & Co., 2011), 30.

-

3No Western scientist would dare to since Edward Saïd’s postcolonial criticism. However, Indian writer Pankaj Mishra suggests rewriting the history of modernism from a specifically Asian perspective in: Temptations of the West: How to Be Modern in India, Pakistan, Tibet and Beyond (New York: Farrar, Straus & Giroux, 2006) and From the Ruins of Empire: The Revolt against the West and the Remaking of Asia (London/New York: Allan Lane, 2012).

-

4See also Ricky Burdett and Deyan Sudjic (eds.), The Endless City (London: Phaidon, 2007).

-

5The exhibition was organized by the MoMA together with the MAK of Vienna and was on show in New York from 22 November 2014 until 10 May 2015. The six cities were Hong Kong, Istanbul, Lagos, Mumbai, New York and Rio de Janeiro. The catalogue was compiled by curator Pedro Gadanho: Uneven Growth. Tactical Urbanisms for Expanding Megacities (New York: Museum of Modern Art, 2014).

-

6The director of the MAK, Christoph Thun- Hohenstein, says in his foreword: ‘It has become abundantly clear that architects will have to be first and foremost social workers if the profession is to retain its relevance and go beyond the “architecture- as-art” glamour projects that some cities and countries still rely on to impress the world.’, ibid., 9.

-

7Balkrishna Doshi, Paths Uncharted (Ahmedabad: Vastu Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design, 2011, second edition 2012), 166; William J.R. Curtis, Balkrishna Doshi. An Architecture for India (Middletown, NJ: Grantha Corporation/Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 1988, reprinted in 2014), 118-135.

-

8In William Curtis’s book, Doshi’s autobiography includes: ‘1967-1971: Member Team 10’, (174), which is remarkable because there was no official group membership. Alison and Peter Smithson contested the idea that Doshi was a member of the group in an interview with Clelia Tuscano in Max Risselada and Dirk van den Heuvel (eds.), Team 10. In Search of a Utopia of the Present (1953-1981) (Rotterdam: NAi Publishers, 2005), 338-339.

-

9Alexander and Doshi jointly published the text ‘Main Structure Concept’ in Landscape, vol. 13 (1963-1964) no. 2, 17-20, reprinted in: Ekistics, vol. 17 (1964) no. 103, 352-354. According to an address list from 1963 kept in the Jaap Bakema archives in Het Nieuwe Instituut in Rotterdam, Alexander used Doshi’s address during his stay in India.

-

10Alison Smithson, Team 10 Meetings 1953-1984 (New York: Rizzoli, 1991), 68-69; Christopher Alexander, Notes on the Synthesis of Form (Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press, 1964).

-

11Doshi himself mentions the residential area for the Electronic Corporation of India in Hyderabad, but that was built between 1968 and 1971, after the Urbino meeting of 1966. In our Team 10 book we mention the industrial neighbourhood in Baroda for the Gujarat State Fertilisers Corporation, which was built between 1964 and 1969. See Risselada and Van den Heuvel, Team 10, op. cit. (note 8), 140- 143; and Doshi, Paths Uncharted, op. cit. (note 7), 241.

-

12Doshi himself mentions the residential area for the Electronic Corporation of India in Hyderabad, but that was built between 1968 and 1971, after the Urbino meeting of 1966. In our Team 10 book we mention the industrial neighbourhood in Baroda for the Gujarat State Fertilisers Corporation, which was built between 1964 and 1969. See Risselada and Van den Heuvel, Team 10, op. cit. (note 8), 140- 143; and Doshi, Paths Uncharted, op. cit. (note 7), 241.

-

13In his book, William Curtis talks about Doshi’s work in terms of an ‘armature over which the chaos of life would play another pattern’. See Curtis, Balkrishna Doshi, op. cit. (note 7), 82.

-

14Balkrishna Doshi, ‘Give Time a Break’, 12-13, part of the collection box Talks by Balkrishna V. Doshi (Ahmedabad: Vastu Shilpa Foundation for Studies and Research in Environmental Design, 2012).

-

15Ibid., 6-7.

-

16Alison Smithson, ‘How to Recognize and Read Mat-Building. Mainstream Architecture as It Has Developed towards the Mat-Building’, Architectural Design, 9 (1974) 590; Smithson also included an example from Ahmedabad: the Museum of Knowledge by Le Corbusier (1949-1957); the building currently houses the city museum, 584.