- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijns

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Marja Elsinga

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Marietta Haffner

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Henk Jonkers

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Self-built

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Chiara Tobia

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Afua Wilcox

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

Inhabitable Voids

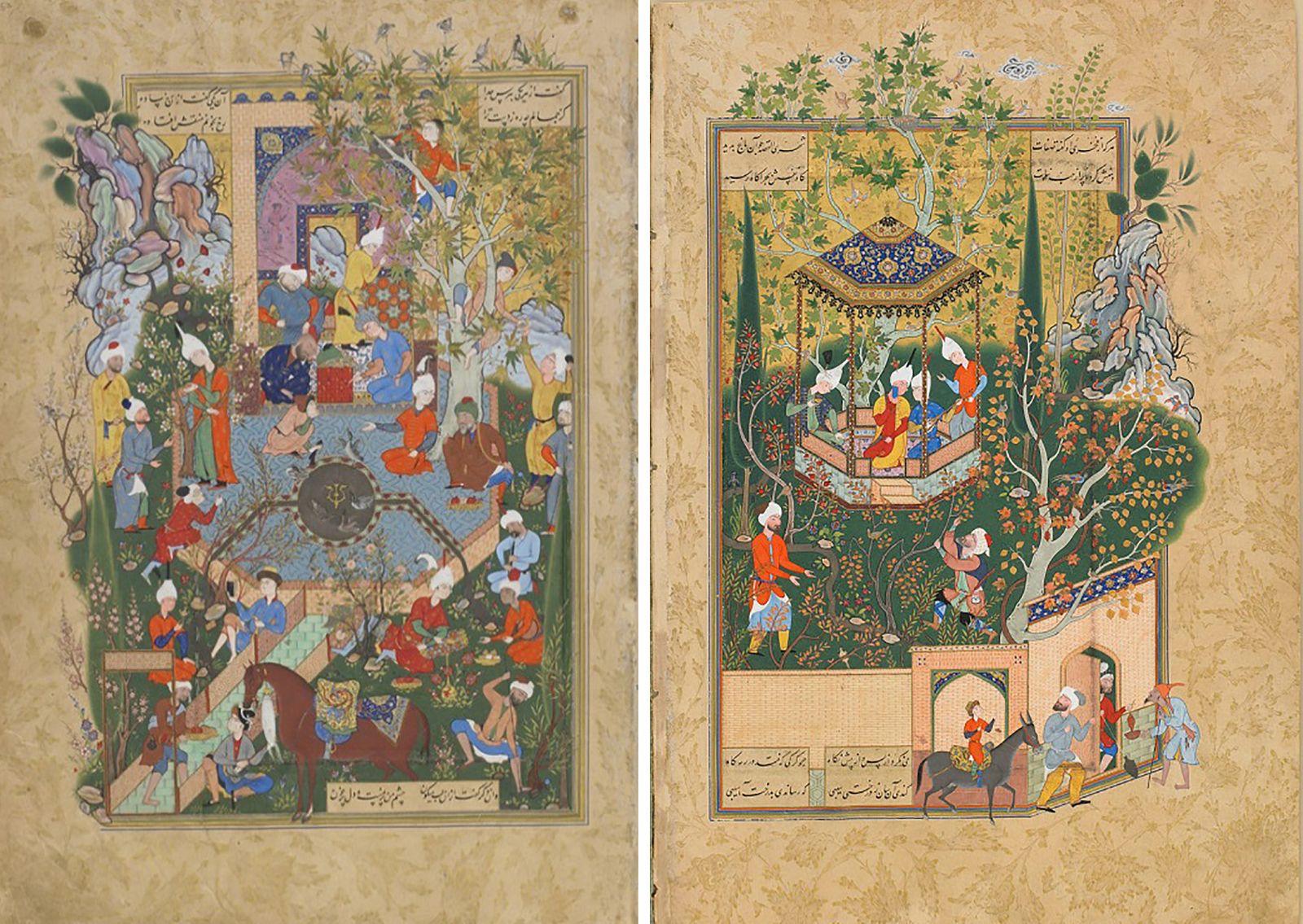

Re-Thinking the Architecture of Appropriate Habitats, Iran

Focusing on the design of large-scale housing schemes, this dissertation examines the extent to which the architecture of dwelling was affected by the modernist logic of architectural design and urban planning in Iran’s period of high-modernisation, as Eskandar Mokhtari termed it, stretching from the post-World War II (WWII) until the 1979 Islamic revolution. It demonstrates the heterotopic void as a means of valorising public spaces and urban communities that have been shaped with the logic of modernist design and planning. Further, this research illustrates how heterotopic voids, such as the Persian Garden and the Courtyard-Garden, through different reinterpretations and in various ways, became a tool for activating collective memory in this modernisation period.

After WWII, Iran underwent a unique process of modernisation. To create a modern nation that would make Iran part of the ‘civilised’ world, the government diffused a notion of ‘modern’ living through the construction of large-scale housing, mostly designed and led by Western-educated Iranian architects. Creating cross-cultural exchanges, these architects fulfilled the mediator role between modernist design principles and Iran’s local architectural culture. Simultaneously, they promoted new lifestyles and living standards among the general public. In the same period that most Middle-Eastern countries experienced a form of urban transformation that was highly influenced and largely led by western urban planners and designers, Iranian architects had the opportunity to develop their own local practices. In fact, through their active engagement in the process of state-led housing development, these architects not only helped the Iranian government to pursue the objectives of the Strategic National Planning and Development, but also, they managed to incorporate some traditional premises of everyday life and vernacular patterns of inhabitation into their housing proposals.

Arguably, the architecture of dwelling was seen as a place to both fulfil the goals of the state’s ambitious modernisation projects, and simultaneously to resist universalising tendencies. In the period of high-modernisation, Iran’s Finance and Planning Organisation prepared five distinct Development Plans, in which housing for middle and low-income families held a prominent place. Indeed, each Development Plan projected the national and international socio-political and economic condition of the time that resulted from rural-urban migrations and the demographic changes being seen in Iran. Accordingly, each Development Plan led to the construction of a series of large-scale housing schemes in urban areas and residential neighbourhoods, among which Kuy-e Chaharsad-Dastgah (1946-48), Kuy-e Narmak (1951-58), Kuy-e Kan (1958-64), Kuy-e Ekbatan (1972-92), and Shushtar-e Nou (1975-85) were designed by leading Iranian architects as prototypical models.

To design these housing prototypes, Iranian architects incorporated a historical, but constantly changing, reading of the heterotopic void. Arguably, they saw the void as an archetypal element of local architectural culture that would establish a system of socio-spatial relationships capable of expressing the meaning of new constructed works. By investigating these housing prototypes developed in five different stages of modernisation in Iran, I argue that while the void as an architectural archetype barley preserved its historical connotation, it remarkably became more heterotopic by being diverse, open, adaptable, and collective, as an urban archetype. Examining this latter form void, thus, would enable architects not only to reflect on the present reality and the development of cities, but also to rethink the significance of the heterotopic void as a main component of housing and appropriate habitats. This understanding is especially crucial today, when our habitats are constantly faced with the challenge of densification and the design of large-scale affordable housing schemes.