- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijn

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

CIDCO Housing

In 1964 Charles Correa, Pravina Mehta and Shirish Patel proposed a radical plan to restructure Mumbai (then Bombay) by developing land across the harbour to accommodate the city’s growing population. Now known as Navi Mumbai, this planned city for 2 million people was built to redirect some of the migration away from Mumbai and help shift the axis of growth in the old city from a monocentric north-south one, to a polycentric urban network around the bay. This, they hoped, would help distribute people and jobs more evenly. But apart from its planning ideals, Navi Mumbai is also well known for its experiments in mass housing. Along with Correa’s Incremental Housing in Belapur (a district in Navi Mumbai), the CIDCO Housing built by the Delhi-based architect Raj Rewal was seen as an answer to the enormous challenge of generating a viable habitat for high-density communities at low cost.

In 1988, the City and Industrial Development Corporation (CIDCO) invited Raj Rewal to develop plans for units of lowcost housing in Belapur. The complex brief called for the design and construction of over a 1,000 units on a hill-side site close to the city’s Central Business District.

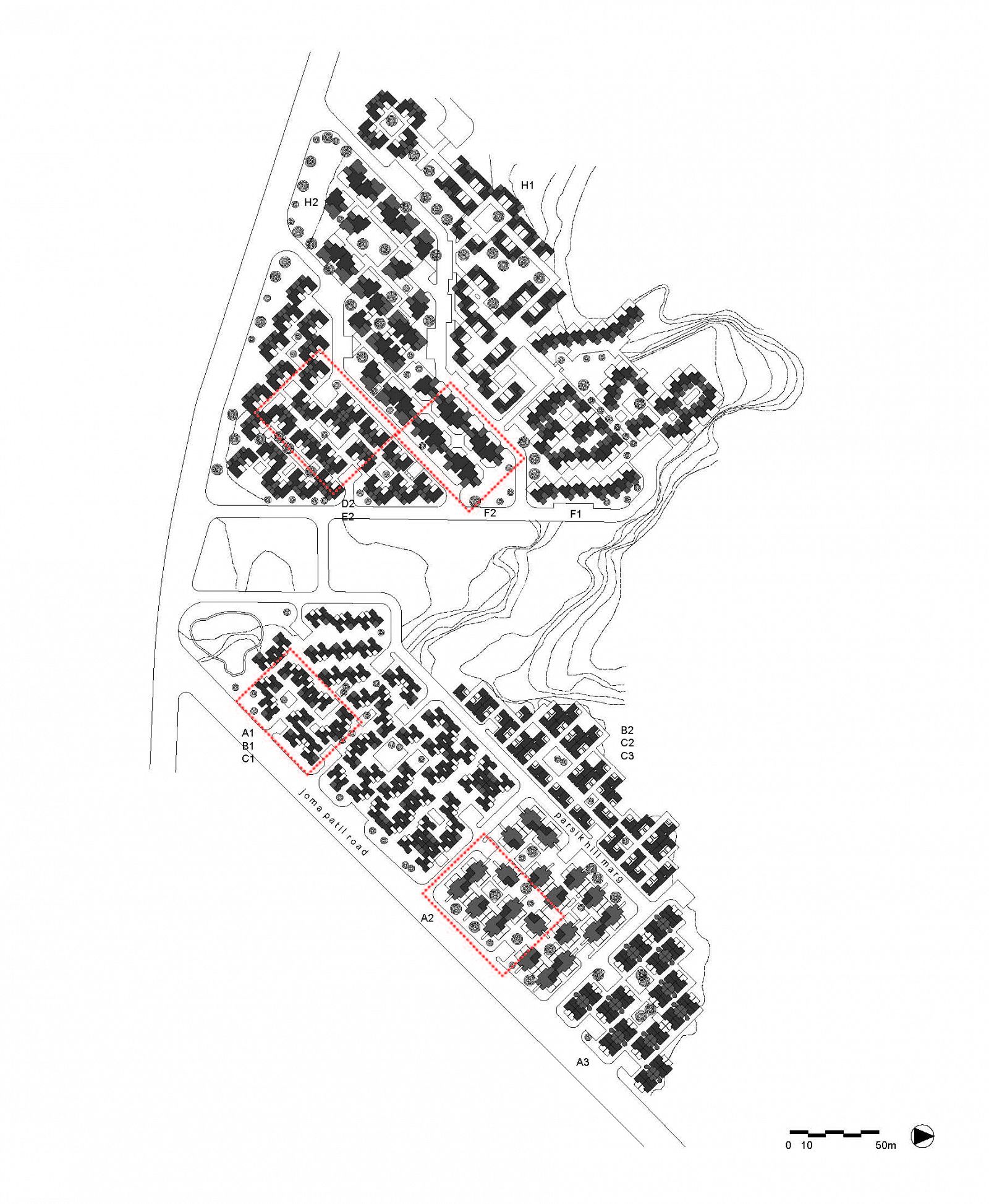

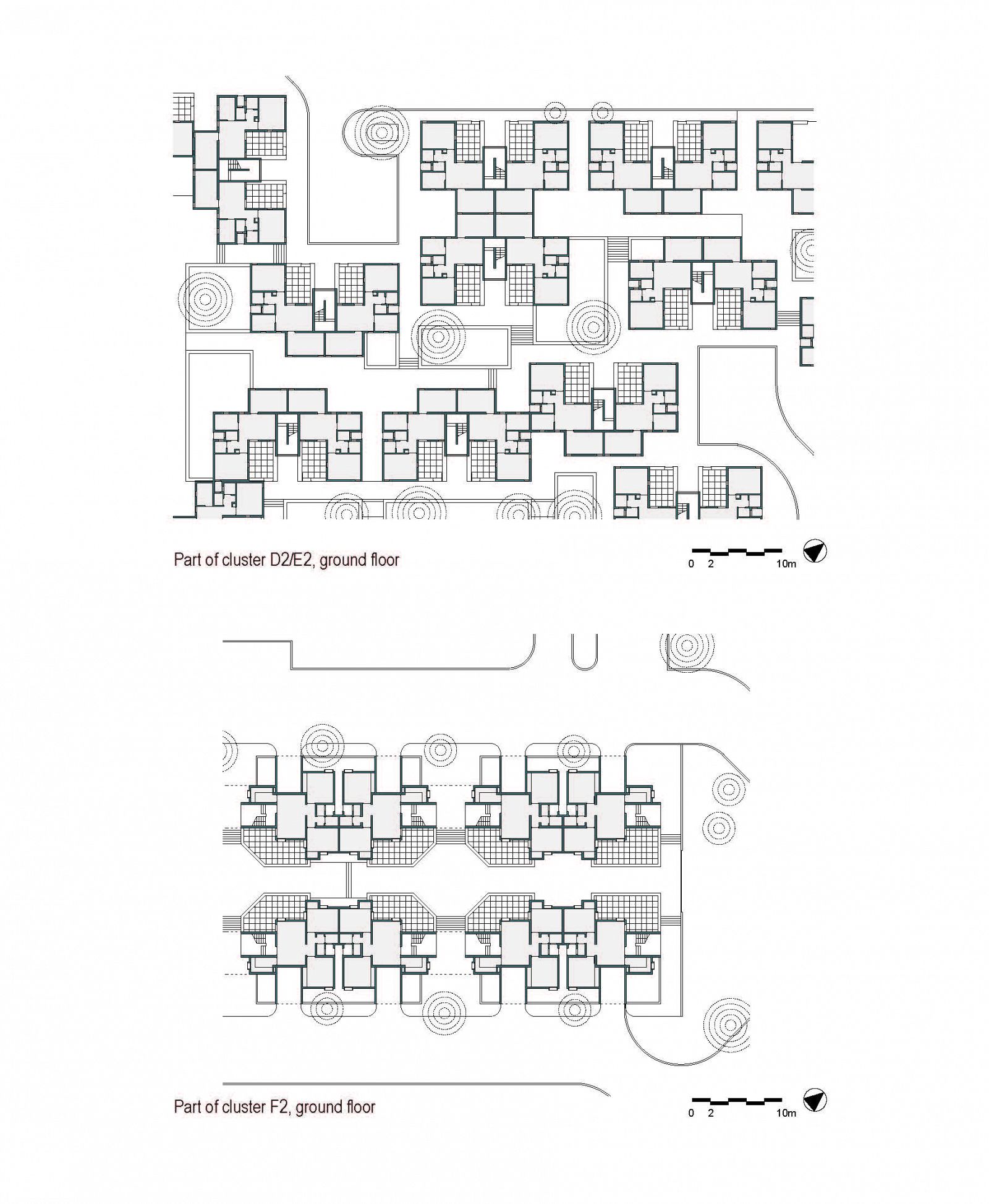

Drawing inspiration from India’s rich reservoir of traditional and vernacular architecture (a recurring feature in his work), Rewal avoided resorting to the typical repetition of large monolithic blocks characteristic of most examples of mass housing. Instead, he created a complex containing a multitude of units and blocks varying in size and configuration (each catering to different income levels and requirements), that form a part of a larger cohesive ensemble, which Rewal himself likes to describe as a ‘string of stories woven into the fabric of one major composition’.

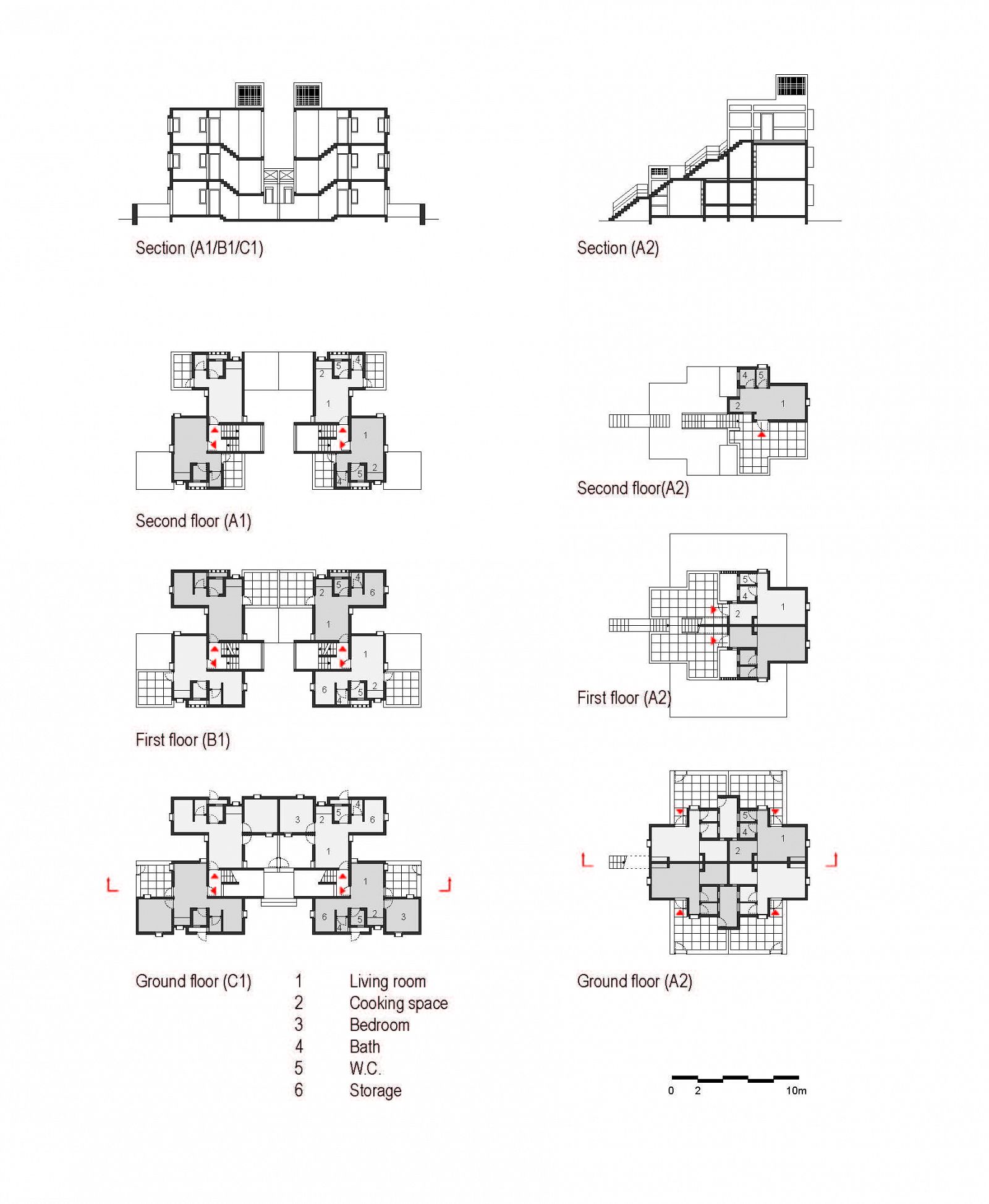

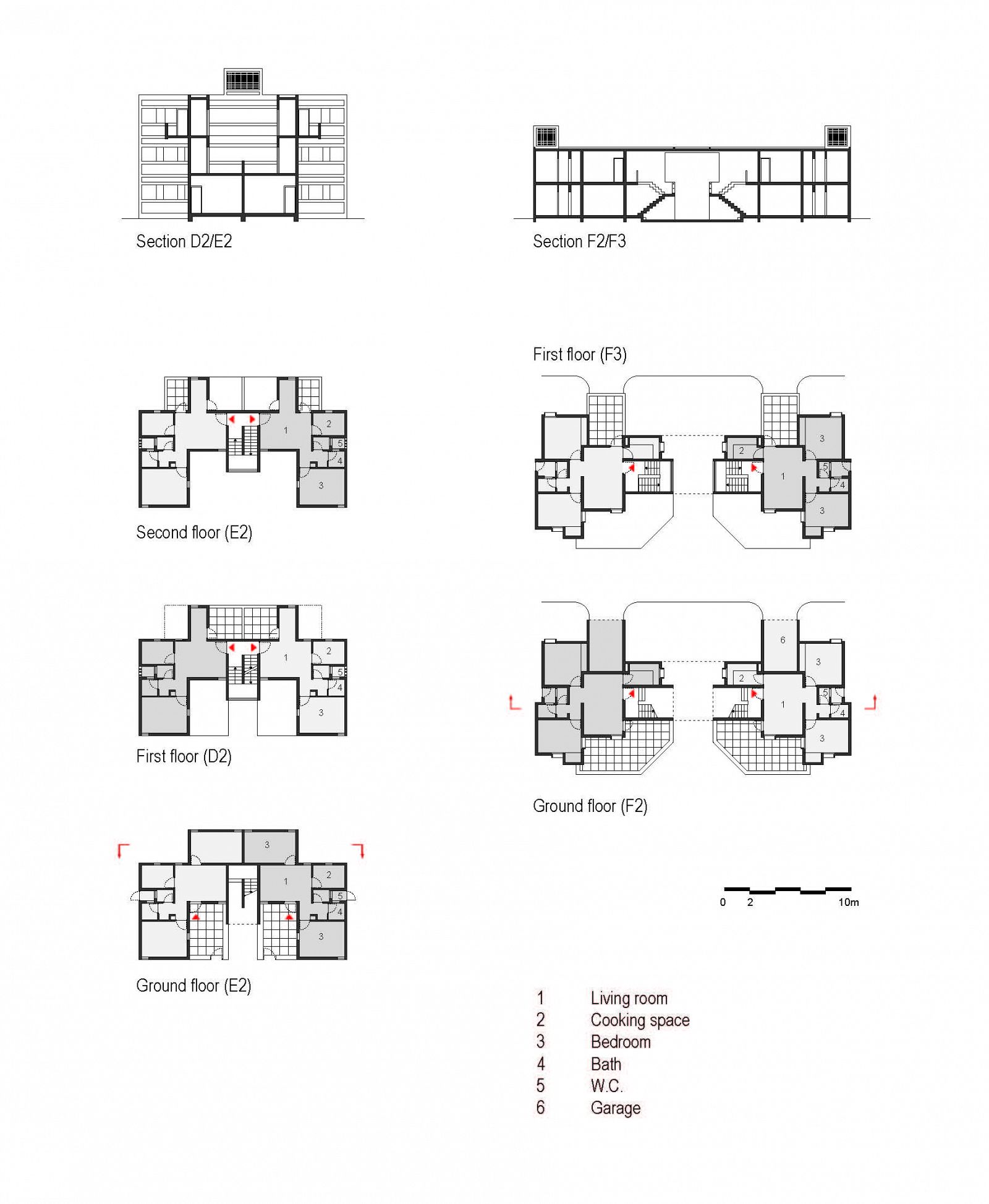

Essentially, the brief was broken down into a number of basic unit types or ‘molecules’ that vary in size from around 20 m2 to 100 m2. Even though these area requirements were fixed by CIDCO, Rewal clearly understood the value of open space that can augment the rather limited areas of the living units themselves. Throughout the design there is an emphasis on creating both private and communal outdoor living areas through the use of courtyards and by staggering and recessing the mass of living units as they go higher to create outdoor roof terraces at different levels.

Another strength of the project lies in the architect’s ability to design several types of living units and blocks ranging from one-room apartments to three-room duplex townhouses. This was crucial as it allowed different income level buyers to choose from a variety of options. At the scale of the entire site, the blocks are arranged in ingenious ways to define seven different types of neighbourhoods. Careful planning also went into ensuring that these neighbourhoods would be pedestrian friendly on the interior with vehicular traffic limited to their peripheries. Moreover, clever usage of the contours of the site allowed for a variety of courtyards and narrow shaded streets at different levels that help provide ample space for interaction and recreation both within and between the neighbourhoods.

What remains consistent throughout the scheme is a careful utilization of space (low-rise high-density planning), economy of construction (industrial production and repetitive use of elements) and choice of materials (locally excavated stone and concrete blocks covered in rough-cast plaster). This enabled Rewal to create a settlement that, while sitting well with its context, has grown and changed to accommodate the needs of the people who live there. However, due to political and administrative reasons such as lack of public transportation, jobs and other amenities, it is unfortunate that today a sizable portion of the neighbourhood lies abandoned. The occupied remainder though, still works as a tight-knit community: a little village where people have colonized and adapted their homes, perhaps in the process resembling even more vividly those old Indian towns that inspired Rewal throughout his career.

Photo: © Rohan Varma

Photo: © Rohan Varma

Drawing: © Delft Architectural Studies on Housing

Drawing: © Delft Architectural Studies on Housing

Photo: © Rohan Varma

Drawing: © Delft Architectural Studies on Housing

Photo: © Rohan Varma