- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijn

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

Shifting Scales

Affordable Housing in India

The search for new models for affordable housing in the world’s growing cities has never been more urgent. Good, inexpensive housing is needed to confront the challenges of urban segregation, and to make it possible for those with little or no means to access and inhabit the cities that have the promise of providing a better future. India has been addressing these issues since its independence in 1947, resulting in a series of housing design experiments that can still inspire, but also clearly demonstrate the near impossibility of finding successful and lasting solutions.

Despite India’s recent economic success, the state’s inability to actively and effectively deal with the country’s rapid urbanization have led to megacities such as Mumbai and New Delhi that threaten to succumb to the unrelenting pressures of distress migration. At the same time, there has been an exponential rise in the number of smaller cities growing at an even faster rate than the large metropolises. Still a predominantly rural society with only about 30 per cent of its entire population living in urban areas (about 410 million people)1, India is expected to add an additional 500 million people to its cities by the year 20502. As urban India surges forward, construction and planning have been unable to keep up with demand, leading to a situation where large informal settlements or slums have become an inevitable consequence of this rapid growth. Today, in India, the enormous task of providing housing for new migrants as well as improving the conditions of those living in the already existing self-built informal settlements has never been more acute.

Designing affordable housing in large numbers is a constant process of balancing opposites. The way people can live in the city is a key factor in the transformation of traditional rural society into a modern urbanized economy. Should affordable dwellings be designed to accommodate a traditional rural way of life, or should they immediately aim for a future urban lifestyle?

The opposites of rural versus urban, of tradition versus modern, and local versus global played a key role in the formation of a new and independent India. Mahatma Gandhi, for example, always stressed the origins of Indian society. ‘India is to be found not in its few cities, but in the 700,000 villages’3 is a famous quote of his from 1936. On the other hand, India’s first Prime Minister, Jawaharlal Nehru, was a firm advocate of the modernization and urbanization of the country, and initiated the construction of a new state capital, Chandigarh, as a symbol of the new, free and modern India.

A New India

Chandigarh, mostly known for its radical urban configuration and famous Capitol buildings designed by Le Corbusier, did indeed have a great impact. Its lasting importance is, however, more related to the design of the housing neighbourhoods than to the design of the major governmental buildings of the Capitol. An orthogonal grid of motorways divides the city into large sectors that each form a village or small town in itself. The wide roads of the grid pattern, lined with trees, make the sectors’ buildings, on average not higher than three floors, almost invisible; hidden villages with a characteristic combination of varied housing types for all classes, along with schools, shops and other amenities. This notion of creating a city out of villages is perhaps the most successful aspect of Chandigarh’s design. It managed to combine the idea of the rural and the urban, reconciling tradition and modernization in a new and unexpected way.

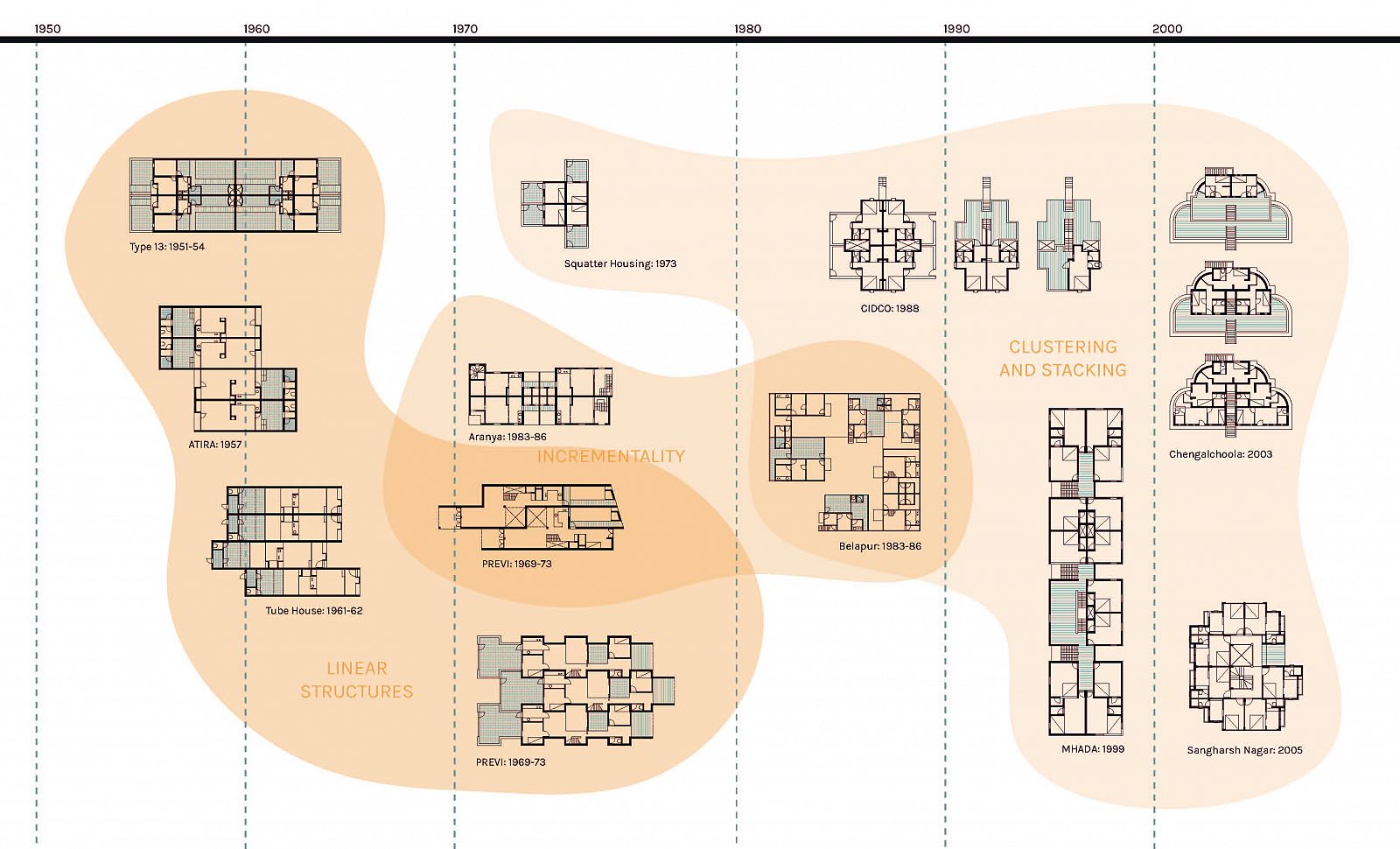

One of the first sectors to be designed and built (1951-1954) was Sector 22. The sector was based on a master plan by Jane Drew, who with her partner Maxwell Fry and Le Corbusier and his cousin Pierre Jeanneret formed the core design team for the first phases of Chandigarh. The sector contains a large variation of housing types, taken form the first ‘catalogue of types’ designed by the team. The Chandigarh climate was well suited to their ambition to work in a modernist idiom; flat roofs with roof terraces on which to sleep, and sun shading elements to make varied, sculptural façades.4

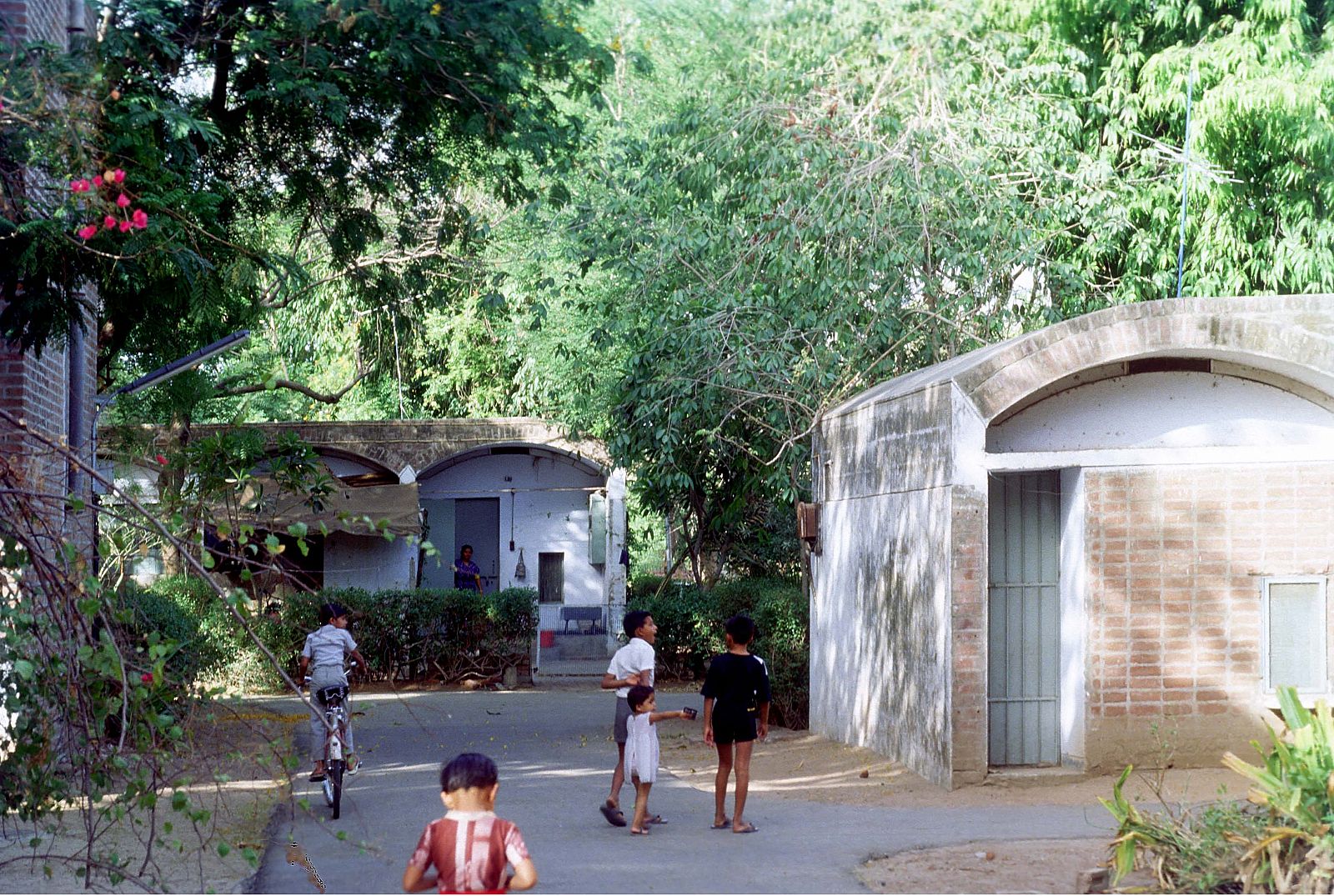

Within their newly invented language, an intelligent combination of local and international influences, Drew herself made a design for type 13. This type was developed as affordable housing for the people serving the middle and higher classes, the so-called ‘peon housing’. Terraces of small and narrow houses were clustered in parallel formations, forming miniature villages within the sector. When planning Chandigarh, Nehru expressed his view on housing the poor: ‘Our cheap housing schemes should be thought of chiefly in terms of providing sanitation, lighting and water supply . . . we can add to this as occasion offers and resources are available.’5

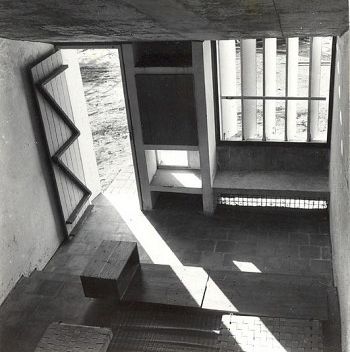

This ‘sites and services’ approach was the point of departure for Drew. However, by means of a very economical way of planning the houses in long parallel rows, she was able to build peon housing that provided both the services and two modest rooms right from the start. The service spaces: kitchen, shower area and WC, were placed in an open configuration in the walled backyard of each house. In Sector 22, the rows of housing were tied together by high walls on the outside boundary, with arched openings giving access to the small streets between the houses. It is an almost archaic play of shapes that emphasizes the houses’ small-scale rural character, in the middle of a new city that is the epitome of modernity. Upon its completion, Nehru commented on Drew’s project that it was the only cheap housing he had seen that did not look cheap.6

Nehru’s wish for the possibility of a gradual growth of the individual house was in keeping with the lifestyle and traditional way of slowly building and extending found in rural areas across India. This idea would come back in many projects; strategies for incremental growth of low-rise housing that were attempted by designers again and again and continue to this day.

Drew and Fry’s housing designs in Chandigarh were not a unique invention. Their earlier projects in Africa informed their projects for Chandigarh, as did some earlier experiments by Indian architects.7 However, their combination of a modernist aesthetic with their use of traditional materials and their responses to climate made their work quite influential, guiding many experiments of housing design, not only in the continuing housing production of Chandigarh designed by local Indian architects, but also in the following 60 years of housing design in India as a whole.

A Community Spine

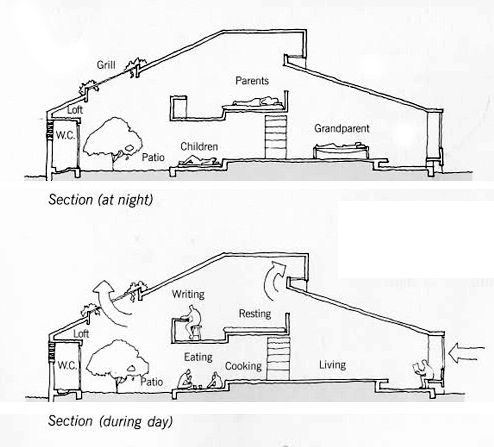

A pioneer in this development was Indian architect Charles Correa (1930-2015). Educated in Michigan and at MIT, Correa started his own practice in Mumbai (then Bombay) in 1958.8 Like his contemporaries, he was from the very beginning of his career interested in issues of affordable housing and planning suited to India’s climate and traditions. In 1961, he participated in a national competition for ideas for low-income housing, organized by the Gujarat Housing Board. The jury, consisting of Jane Drew and Indian architect Achyut Kanvinde, who had studied under Walter Gropius at Harvard, awarded the first prize to Correa’s inventive Tube House design. Inspired by the wind-catcher houses found in Sind in Pakistan, Correa managed to achieve the densities required with long and narrow terraced houses, with the section as the main figure of the design. An exploration of the possibility of cross ventilation and of a minimization of materials led to the design of a house, closed to its surroundings, but opening up internally to a central patio and to the sky (a recurring feature in Correa’s work). Small differences in floor levels of the ground floor and mezzanine marked places for eating, cooking, sleeping and sitting without the use of internal partition walls, thus enabling efficient cross ventilation and a reduction of costs.

The Tube House is an early example of Correa’s belief that ‘form follows climate’.9 In fact, the project’s themes continued to inform Correa’s work, and led to a rich and consistent series of designs for affordable housing, although regrettably, many of these remained unbuilt. Correa further explored the efficiency of the narrow terraced house as a typology in his contribution to the famous PREVI experimental housing project in Lima, Peru. The central theme of this limited invited competition, organized in 1969 for 13 architects from Peru, and 13 international architects (including the likes of Aldo van Eyck, James Stirling and Christopher Alexander) was to develop designs for affordable dwellings in low-rise, high-density configurations that would allow for incremental growth.10

Correa’s response to the design brief was to develop a long and narrow patio plan, clearly inspired by Christopher Alexander’s and Serge Chermayeff’s studies for the ideal American suburban home as published in their 1963 book Community and Privacy.11 However, realizing the drawbacks of living in a very strict narrow space from his earlier projects such as the Tube House and the Cablenagar Township (unbuilt, 1967) in Kota, Rajasthan, Correa instead favoured a design where, for a part of the house’s length, the width is doubled to create more variety. By placing the double-width part of the houses in different positions, the houses start to interlock, creating both variety in plan, an individual articulation expressed in the exterior, and a more stable structure for the loadbearing masonry walls. At the larger scale there is a clear separation between pedestrian and vehicular access. The units have access at the rear for cars, while the front doors are oriented towards a pedestrian space that Correa named the community spine, bringing into mind another American invention; the Radburn principle.

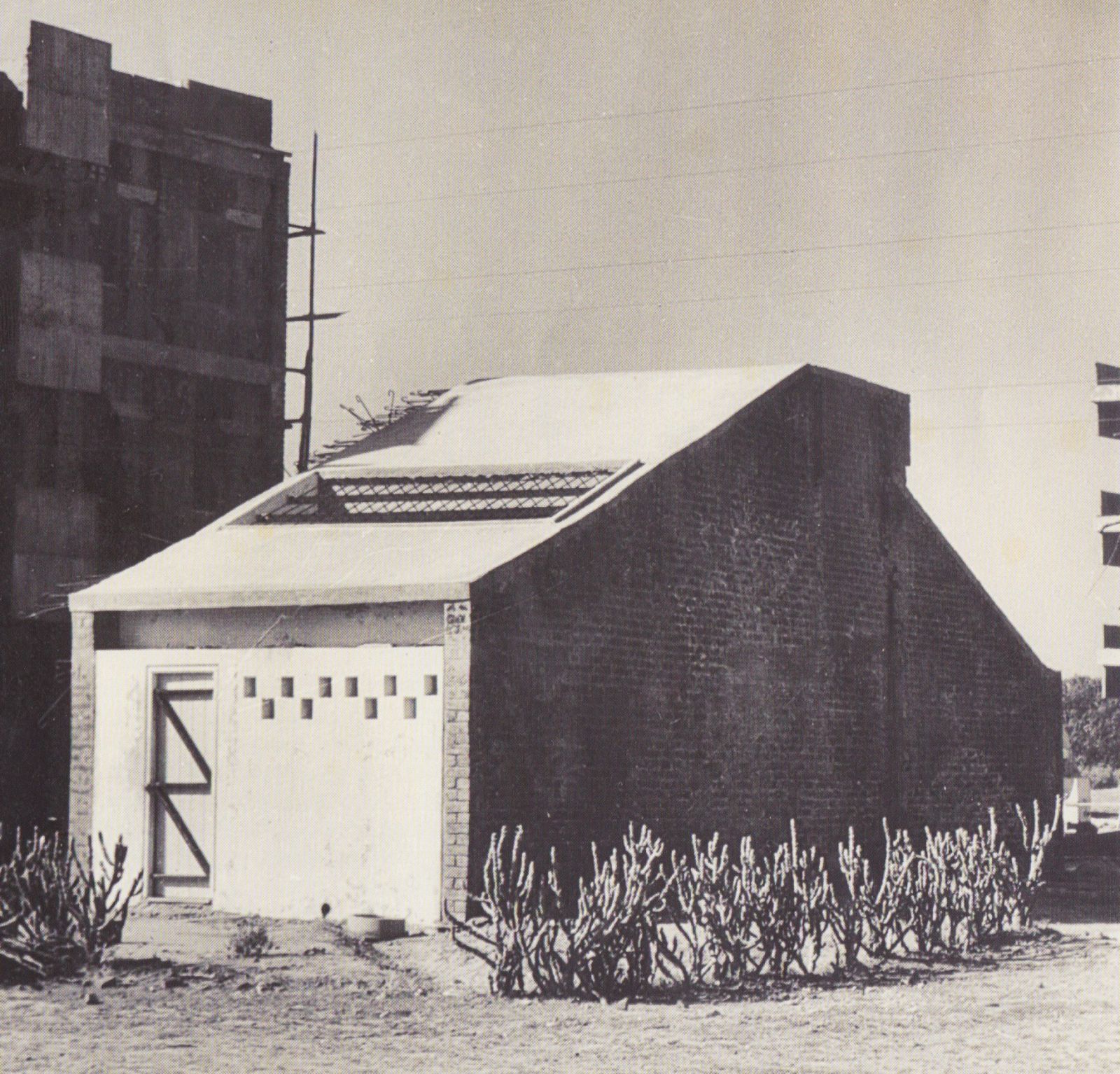

Although the PREVI project was not built entirely as planned, the collective space, created between the units by means of its pattern of clustering, became an important element in Correa’s later work. One of these is the design for Squatter Housing in Bombay of 1973, again unbuilt. It is the simplest of all his designs, but has a strong promise in creating a collective space through its possibilities of clustering. Very simple square, one-room units, each of only 9 m2, are connected in groups of four under one pyramidal roof. Each unit has a walled courtyard, also of 9 m2, that serves as an outdoor living space, mediating between the private and collective spaces. The courtyard walls that encircle these outdoor spaces make it possible to connect the groupings of four units in larger clusters, creating fractal patterns, an element further developed into very complex structures in later projects. As compared to the more regular, urban rows of the Tube House or PREVI project, this method of clustering is more reminiscent of the layout found in Indian villages with their shared open spaces, and marks a key shift in the work and thinking of Correa.

However, Correa’s best-known plan for affordable housing remains the Incremental Housing project located at Belapur in New Bombay. Designed in 1983, this project brings together all the themes that were explored in his earlier work. The project is characterized by a variety of types and sizes of individual units, ranging from single-room units to urban townhouses. Each of these are free-standing units that have the possibility to grow and change over time, made possible by the use of simple traditional building techniques and by a set of rules that allow for incremental growth. Thus, over time, even the most basic small oneroom units have gradually grown into substantial two-storey houses. At the larger scale, the entire scheme is formed by the repetition of clusters at different scales that results in complex fractal patterns that together form a neighbourhood for 600 families with a clear hierarchy of private and community spaces.

A Growing Village

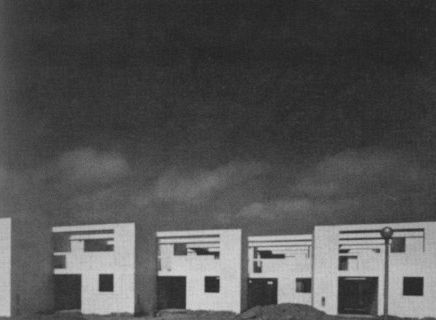

Correa’s colleague Balkrishna Doshi (b. 1927) followed a parallel process in developing models for affordable housing that address issues of density and incrementality.12 Doshi, who worked for Le Corbusier for close to seven years, first at his atelier in Paris and later as his assistant in Chandigarh and Ahmedabad, as well as with Louis Kahn for the Indian Institute of Management, also in Ahmedabad, has played a seminal role in the development of modern architecture in India. Due to his close proximity to Le Corbusier, Doshi’s first designs show, even more than Correa’s, a strong Corbusian influence, as found in the pattern of parallel and staggered terraced houses for the ATIRA houses project in Ahmedabad of 1957. The Life Insurance Corporation (LIC) Colony, built in 1973, also in Ahmedabad, showed when finished a pristine modernist appearance, bringing back images of the heroic period of the Modern Movement, such as J.J.P. Oud’s design for terraced housing. The design has a stepped profile across three floors, where each upper level has a smaller footprint creating terraces that allow for incremental growth over time.

Doshi’s ideas of low-income housing and incrementalism are probably best described in his project in Aranya, Indore. Designed in the 1980s, around the same time as Correa’s Belapur project, it combines the themes of incremental growth and the mixing of classes and unit types. Funded and promoted by the World Bank, the project resonated with both Nehru’s vision for affordable housing, as well as with the much-publicized research on the idea of ‘sites and services’ popularized by British architect John Turner in the context of Peru in the early 1960s.

Designed to eventually house a population of 60,000 people in some 6,500 dwellings across 85 ha, Doshi’s master plan included a network of roads, pathways and open spaces. At the scale of the houses themselves there was a great variety in the type and size of plots available to different income groups. The poor, for example, were given just a plinth and service core that could be expanded by them into larger houses at a later time. However, apart from providing a detailed master plan, Doshi’s office was also responsible for designing and building 80 demonstration houses, with the intention that future residents of this site could learn and educate themselves about the possibilities of each of their individual plots. Local materials, such as brick and stone, but also concrete, were made easily available and residents were allowed to use any material to build. Today, Aranya has grown to resemble a typical Indian town where narrow streets are shaded by a variety of houses, ranging from ground-floor dwellings to three-storeyhigh urban townhouses.

A Vertical Village

The idea of stacking clusters of housing units in village-like configurations to create even higher densities has been thoroughly explored since the 1960s by another Indian architect: Raj Rewal (b. 1934).13 Educated in Delhi and London, Rewal worked in the office of Michel Écochard in Paris, before setting up his own practice in New Delhi. Over the last three decades, Rewal has managed to develop a consistent oeuvre of housing projects all based on the idea of stacking and staggering units clustered around courtyards inspired by the vernacular architecture of India. This results in very complex and varied ensembles that clearly refer to the fabric and silhouettes of the historical Indian towns, such as Jaisalmer in Rajasthan and Leh in Ladakh.

Rewal applied these principles to all categories of housing; in affordable housing and in housing for middle and upper-middle income groups. A clear example of his design principles can be found in the early Sheikh Sarai Housing project of 1970, which contains apartments for different sections of society. A dense pattern of low-rise, high-density blocks are situated around a network of collective open spaces linked by shaded pedestrian pathways. The units are organized in two basic cluster forms. Each unit has an outside terrace with a protective, high and perforated parapet wall. The concrete frame structure with brick infill has a continuous white pebbledash finish. The result is both a consistent and complex system of shapes, spaces and movement, an abstract afterimage of a typical Indian village with shaded streets, communal courtyards and open terraces.

Variations on this system of clustering and stacking with terraces were used for the design of the impressive Asian Games village (New Delhi, 1980-1982) and many other projects. Most remarkable is the low-income housing project for the City and Industrial Development Corporation (CIDCO) built in 1988 in New Bombay (Navi Mumbai). It was conceived entirely to provide affordable housing for the lowest income groups on a challenging hillside site near the city’s financial district. We find here again a megastructure of interlinked courtyards and passageways defined by buildings two to four storeys tall that are clustered around collective spaces and staircases. The units’ sizes range from 18 to 105 m2, with more than 75 per cent of them being smaller than 42 m2 in area, all choreographed ingeniously to create neighbourhoods at different scales, with clearly defined private and collective areas.

From Low- to High-Rise

Rewal’s designs are clearly a part of a utopian vision of the stacked village, obsessively pursued by the post-war modernists of Team 10, the Dutch Structuralists and the Japanese Metabolists. However, despite the ingenious clustering and stacking of Rewal’s projects, the achieved densities remain relatively low, about 100 to 200 units per hectare. To translate successful low-rise affordable housing concepts into vertically organized housing projects in high densities that can meet the incredible pressures of urbanization in India seems an impossible ambition.

For his well-known Kanchanjunga Tower project in Mumbai (1970- 1983), Correa again picked up the idea of the complex section of the Tube House, but this time for the design of a high-rise luxury tower. The building methods needed to achieve a complex section, quite simple in low-rise houses, become incredibly complex and expensive when translated into a high-rise building. In the Kanchanjunga Tower, the intelligent stacking of different sections, the insertion of double-height corner patios that respond to climate, the layout of two apartments per floor around one access, have all worked together to create an exceptional and sculptural project, but certainly not one that can be a used as a recipe for affordable housing.

Correa’s only high-rise project that deals with higher densities for low-income groups is his project for the Maharashtra Housing and Development Authority (MHADA), which called for the building of transit camps for Mumbai’s displaced urban poor. Designed in 1999, the concept is based on the clustering of four small units, each with a corner position that allows for cross ventilation, as in the Squatter Housing project of 1970. Through a clever arrangement of access cores placed between the stacked clusters, and by taking out a number of units at different levels, Correa was able to reduce the number of elevators and create collective places for community activities. The project, however, remained unbuilt and the opportunity to measure the success of such a design was lost.

An Outsider

When we analyse the work of Correa, Doshi and Rewal, we find a careful and consistent approach that seeks to integrate local ways of living, building methods and culture with the new techniques and aesthetics of twentieth century modernism. A very different continuity can be found in the work of an outsider, Laurie Baker. This English architect (1917-2007) lived and worked for more than 50 years in India and is widely acknowledged as an authority on low-cost design in the country, although he remains relatively unknown.14 Unlike Correa, Doshi and Rewal, the work of Baker was not overly influenced by the teachings of the Modern Movement. He instead based his architecture on the traditional masonry crafts of Kerala, the most southern Indian state, where he built most of his work. His use of traditional techniques, the responsiveness towards climate and culture, and the emphasis on low-cost design led to a series of remarkable projects for private houses and small institutional buildings.

Late in his working life, he built a project for affordable housing in Kerala’s capital city, Trivandrum. The Chengalchoola Slum Development housing project was designed as the replacement of an existing informal settlement. Since 2003, a series of housing blocks were built, each block consisting of ten units; five on the ground floor, three on the first and two on the second floor. This allows for a stepped section with terraces for all upper units. The block appears as a village house, built in brick with a sloping roof, enlarged to a more urban scale. At the same time, each building can be seen as a miniature village, reduced to the scale of a single building, as if the ten units were built on a slope with a staircase as a connecting pathway.

As in all of his work, Baker made careful use of materials. The use of concrete has been minimized, and there is instead an emphasis on bamboo reinforcement, bamboo piles and brick loadbearing walls. This sensitivity towards the possibilities of the specific and local techniques is quite extraordinary, and probably needed the eye of an outsider like Baker.

Lost Ideals

But again, Baker’s project cannot address the scale of growth in Indian cities and the densities required to rehabilitate the existing informal settlements that are a part of these cities. The brutal reality is that impatient growth and growing segregation are inextricably linked. Chandigarh, for example, was designed as an expression of the ideals of a newly independent India that could accommodate both the rich and the poor. Today Chandigarh is a far cry from what it was once imagined to be. While it is certainly one of the wealthiest cities in India, its social ideals are severely threatened by increasing urban segregation, which can be seen both in the early sectors as well as in the most recent developments. And this isn’t a new trend. Even as far back as the 1980s, it was becoming increasingly clear that the speed of urbanization taking place in India far outpaced the ability of the authorities to keep up with demand. Across India, and the world, slum upgrading projects and self-help projects were failing to reach the scale of demand needed, which prompted international agencies such as the World Bank and the International Monetary Fund (IMF) to champion a greater role of the private sector by reducing the role of the state. Such an ‘enabling’ strategy perfectly fit the neoliberal agenda of the time, including that of India, and led to a policy of decentralization – essentially reducing the dispersal of power and responsibility of the government while increasing the role of the market. In terms of housing, this meant an increased privatization of the delivery of housing stock.

This new trend is evident in cities like Mumbai, where the private sector is now increasingly producing the bulk of affordable housing, with the state acting merely as a facilitator in the process. Under the controversial Slum Rehabilitation Scheme (SRS), implemented in 1995, eligible families living in recognized slums are rehoused on existing plots at a higher density in medium- to high-rise tenements. This is entirely cross-subsidized by the private developer in exchange for a large portion of that land, which can then be used for new market housing. Thus, affordable housing is increasingly being treated solely as a landcentric problem where the emphasis is on maximizing profits by adding densities at the cost of the average slum dweller, while ignoring their existing living patterns and their need for essential social amenities such as schools, hospitals and open spaces.

It is perhaps this shift in India, from a socialist nation right from the time of its independence to its transition into a capitalist economy today that has played the biggest role in the production of housing in the country. In this new context (unlike in the era when Correa, Doshi and Rewal built their best-known affordable housing projects), architects practising in India today have lost, for the most part, the government as a client. With the private sector uninterested in issues of equality and social inclusiveness, the situation is getting worse in urban areas every day. This has led to the emergence of a number of different models of architectural practices, ranging from ‘architect-activists’ to ‘not-for-profit’ firms that challenge the government and their approach towards affordable housing.

Opposite Scales and Numbers

P.K. Das, an architect based in Mumbai, is one such example.15 Realizing the reality of the current situation, Das has been collaborating with an organization called the Nivara Hakk Welfare Centre to build a few projects as alternatives to the standard slum rehabilitation projects being built all over the city. Sangharsh Nagar, a large colony built in 2005 in Mumbai, is perhaps their best-known project. Here, Das has been compelled to work within the rules of the SRS to provide housing for almost 18,000 families that were forcibly evicted from their homes as part of the city’s Slum Clearance policy in 1995. Faced with the enormous task of providing housing at a very high density of almost 500 dwellings per hectare, Das based his design on the clustering of eight-storey apartment buildings arranged around communal courtyards. Although he was able to avoid the typical rubber stamping that characterizes most such projects, the densities required have proven too much to be able to incorporate local and traditional ways of living into this medium- to high-rise configuration. Thus, rather than the staggered profiles of projects by Doshi or Rewal, with open terraces at different levels and narrow shaded streets in between, here one finds a far more simple arrangement of five to six apartments placed around a central circulation core.

While P.K. Das is concerned with the necessity of building for the masses at a large scale, at the other end of the spectrum another type of practice has emerged that is more inclined towards bottom-up approaches and small-scale interventions. Rather than attempt whole-scale redevelopment, organizations such as URBZ believe in the power of grassroots movements and ground-up strategies to improve the quality of life in settlements in cities such as Mumbai.16 In fact, URBZ is located within Dharavi – Mumbai’s and Asia’s largest slum. Run primarily by the duo Rahul Srivastava, an anthropologist, and Matias Echonave, an urban planner, URBZ regularly organizes workshops and collaborates with communities and other private and educational institutions to carry out surveys and document research and to speculate on possible alternatives to standard models of development.

One of the projects they have been involved in for a very long time is opposing and suggesting alternatives to the government’s controversial Dharavi Redevelopment Plan (DRP). Poles apart from the proposed plan, which is a clear case of profit over people, URBZ instead advocates a John Turner-inspired approach that would allow the residents themselves to decide the future of their own neighbourhoods. Apart from playing the role of activist, the URBZ team works with local masons and contractors to provide design and technical advice to residents who wish to undertake improvements of their homes. Over the years, they have been able to assist in upgrading a few such houses that were once nothing more than temporary shacks into two- or three-storey stable structures.

A similar approach involving in situ upgrading has been adopted by a New Delhi-based organization called microHome Solutions (mHS).17 Set up in 2009 and run by the husband-wife team of Marco Ferrario, an architect, and Rakhi Mehra, an economist, mHS has, like URBZ, been strongly advocating an approach that catalyses the self-building capacities of people in informal settlements. Over the past six years since the start of the organization, mHS has been working on a variety of projects, ranging from temporary shelter for the homeless to the proposed redevelopment of an entire slum in New Delhi. But what sets mHS apart is that it looks to provide not only spatial and technical advice, but also financial assistance as in the case of Mangolpuri, a resettlement colony in Delhi. Here, in collaboration with a microfinancing organization, mHS was able to assist 15 families with the construction of two-storey structures that were more stable and better ventilated than the temporary structures they had been living in.

An Indian Future

The work of organizations like URBZ, mHS, but also of P.K. Das for that matter, represent a new breed of architects working in India operating at different scale levels. Through collaborations and activism, they are actively using the democratic setup of India to resist market forces and are in reality doing pioneering work to improve the living conditions of informal settlements through self-organization, self-help and small-scale upgrading. But again, looking at the scale of growth that lies ahead, such models hardly seem able to provide all the answers to India’s urbanization, which will perhaps be one of humanity’s biggest challenges in the coming 50 years. By the year 2025, India is expected to surpass China as the world’s most populous country.18 And by the middle of this century it will be home to more than 1.6 billion people – of which more than 50 per cent (about 875 million people) will be living in urban centers.19 As stated in the introduction, this means that between now and 2050, India will be registering the largest increase in urban population of any country by adding almost 500 million people to its cities.

As dumbfounding as these numbers are, they should not distract from the key questions related to the design and construction of affordable housing. India has a unique and rich architectural legacy of affordable housing projects that bring together tradition and modernity; at the scale of the material, the dwelling, the neighbourhood and the city. Small as they may seem today in numbers, the significance of the Indian experiments in affordable housing is clear; they all attempt not only to provide basic shelter, but to create spaces that enable inhabitants to become a part of a community and the city. Building housing that create those spaces is still the essence of architecture, and the only way to make cities that are livable and accessible for everyone.

-

1http://www.worldometers.info/worldpopulation/india-population/. Accessed 16 August 2015.

-

2A. Dhar (2012), India Will See Highest Urban Population Rise in Next 40 Years,available online at: http://www.thehindu.com/news/india-will-seehighest-urban-population-rise-in-next-40-years/article3286896.ece. Accessed 16 August 2015.

-

3Speech by Mahatma Gandhi at the 50th session of the Indian National Congress, Faizpur, Bangalore, in: A.K. Thakur, Economics of Mahatma Gandhi: Challenges and Development (Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications, 2009).

-

4For documentation of Drew’s contributions to the design of Chandigarh, see: Kiran Joshi, Documenting Chandigarh, the Indian Architecture of Pierre Jeanneret, Edwin Maxwell Fry, Jane Beerly Drew (Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 1999); Tom Avermaete and Maristella Casciato, Casablanca Chandigarh, A Report on Modernization (Zurich: CCA and Park Books, 2014); Iain Jackson and Jessica Holland, The Architecture of Edwin Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, Twentieth Century Architecture, Pioneer Modernism and the Tropics (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2014).

-

5Jackson and Holland, The Architecture of Edwin Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, op. cit. (note 4), 233.

-

6Ibid., 235.

-

7Drew and Fry published several books on their experience of designing housing in tropical climates: (with Harry L. Ford) Village Housing in the Tropics: With Special Reference to West Africa (London: Lund Humphries, 1947); Tropical Architecture in the Humid Zone (London: Batsford, 1956); Tropical Architecture in the Dry and Humid Zones (London: Batsford, 1964).

-

8For an overview of Correa’s housing designs, see: Charles Correa, Housing & Urbanization (Bombay: Urban Design Research Institute, 1999); Charles Correa and Kenneth Frampton, Charles Correa (London: Thames & Hudson, 1996).

-

9Vincent B. Canizaro (ed.), Architectural Regionalism: Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity, and Tradition (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007).

-

10For a recent study on the PREVI project and its development over time, see: Fernando García-Huidobro, Diego Torres Torriti and Nicolas Tugas, Time Builds! (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 2008).

-

11Christopher Alexander and Serge Chermayeff, Community and Privacy: Toward a New Architecture of Humanism (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1963).

-

12For an overview of Doshi’s housing designs, see: James Steele, The Complete Architecture of Balkrishna Doshi: Rethinking Modernism for the Developing World (London: Thames & Hudson, 1998); William J.R. Curtiss, Balkrishna Doshi, An Architecture for India (Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 2014).

-

13For an overview of Rewal’s work, see: Suparna Rajguru and Raj Rewal, Innovative Architecture and Tradition (New Delhi: OM Books International, 2013).

-

14For an overview of Baker’s work, see: Gautam Bhatia, Laurie Baker, Life, Work & Writings (Gurgaon: Penguin Books India, 1991).

-

15For an overview of Das’s work, see: http://www.pkdas.com.

-

16For an overview of the work of URBZ, see: http://www.urbz.net.

-

17For an overview of the work of Micro Home Solutions, see: http:// microhomesolutions.org.

-

18S. Roberts (2009), In 2025, India to Pass China in Population. Available online at: http://www.nytimes.com/ 2009/12/16/world/asia/16census. html?_r=0. Accessed 3 March 2013.

-

19Dhar, India Will See, op. cit. (note 2).

Source: © Charles Correa Foundation

Source: © Charles Correa Foundation

Photo: © Vastu Shilpa Foundation, Ahmedabad

- 1 A New India

- 2 A Community Spine

- 3 A Growing Village

- 4 A Vertical Village

- 5 From Low- to High-Rise

- 6 An Outsider

- 7 Lost Ideals

- 8 Opposite Scales and Numbers

- 9 An Indian Future

-

1http://www.worldometers.info/worldpopulation/india-population/. Accessed 16 August 2015.

-

2A. Dhar (2012), India Will See Highest Urban Population Rise in Next 40 Years,available online at: http://www.thehindu.com/news/india-will-seehighest-urban-population-rise-in-next-40-years/article3286896.ece. Accessed 16 August 2015.

-

3Speech by Mahatma Gandhi at the 50th session of the Indian National Congress, Faizpur, Bangalore, in: A.K. Thakur, Economics of Mahatma Gandhi: Challenges and Development (Delhi: Deep and Deep Publications, 2009).

-

4For documentation of Drew’s contributions to the design of Chandigarh, see: Kiran Joshi, Documenting Chandigarh, the Indian Architecture of Pierre Jeanneret, Edwin Maxwell Fry, Jane Beerly Drew (Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 1999); Tom Avermaete and Maristella Casciato, Casablanca Chandigarh, A Report on Modernization (Zurich: CCA and Park Books, 2014); Iain Jackson and Jessica Holland, The Architecture of Edwin Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, Twentieth Century Architecture, Pioneer Modernism and the Tropics (Farnham: Ashgate Publishing, 2014).

-

5Jackson and Holland, The Architecture of Edwin Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, op. cit. (note 4), 233.

-

6Ibid., 235.

-

7Drew and Fry published several books on their experience of designing housing in tropical climates: (with Harry L. Ford) Village Housing in the Tropics: With Special Reference to West Africa (London: Lund Humphries, 1947); Tropical Architecture in the Humid Zone (London: Batsford, 1956); Tropical Architecture in the Dry and Humid Zones (London: Batsford, 1964).

-

8For an overview of Correa’s housing designs, see: Charles Correa, Housing & Urbanization (Bombay: Urban Design Research Institute, 1999); Charles Correa and Kenneth Frampton, Charles Correa (London: Thames & Hudson, 1996).

-

9Vincent B. Canizaro (ed.), Architectural Regionalism: Collected Writings on Place, Identity, Modernity, and Tradition (New York: Princeton Architectural Press, 2007).

-

10For a recent study on the PREVI project and its development over time, see: Fernando García-Huidobro, Diego Torres Torriti and Nicolas Tugas, Time Builds! (Barcelona: Gustavo Gili, 2008).

-

11Christopher Alexander and Serge Chermayeff, Community and Privacy: Toward a New Architecture of Humanism (Garden City, NY: Doubleday, 1963).

-

12For an overview of Doshi’s housing designs, see: James Steele, The Complete Architecture of Balkrishna Doshi: Rethinking Modernism for the Developing World (London: Thames & Hudson, 1998); William J.R. Curtiss, Balkrishna Doshi, An Architecture for India (Ahmedabad: Mapin Publishing, 2014).

-

13For an overview of Rewal’s work, see: Suparna Rajguru and Raj Rewal, Innovative Architecture and Tradition (New Delhi: OM Books International, 2013).

-

14For an overview of Baker’s work, see: Gautam Bhatia, Laurie Baker, Life, Work & Writings (Gurgaon: Penguin Books India, 1991).

-

15For an overview of Das’s work, see: http://www.pkdas.com.

-

16For an overview of the work of URBZ, see: http://www.urbz.net.

-

17For an overview of the work of Micro Home Solutions, see: http:// microhomesolutions.org.

-

18S. Roberts (2009), In 2025, India to Pass China in Population. Available online at: http://www.nytimes.com/ 2009/12/16/world/asia/16census. html?_r=0. Accessed 3 March 2013.

-

19Dhar, India Will See, op. cit. (note 2).