- Angola, Uíge

- Bangladesh, Dhaka

- Bangladesh, Sylhet

- Bangladesh, Tanguar Haor

- Brazil, São Paulo

- Chile, Iquique

- Egypt, Luxor

- Ethiopia, Addis Ababa

- Ghana, Accra

- Ghana, Tema

- Ghana, Tema Manhean

- Guinee, Fria

- India, Ahmedabad

- India, Chandigarh

- India, Delhi

- India, Indore

- India, Kerala

- India, Mumbai

- India, Nalasopara

- India, Navi Mumbai

- Iran, multiple

- Iran, Shushtar

- Iran, Tehran

- Italy, Venice

- Kenya, Nairobi

- Nigeria, Lagos

- Peru, Lima

- Portugal, Evora

- Rwanda, Kigali

- Senegal, Dakar

- Spain, Madrid

- Tanzania, Dar es Salaam

- The Netherlands, Delft

- United Kingdom, London

- United States, New York

- United States, Willingboro

- 2020-2029

- 2010-2019

- 2000-2009

- 1990-1999

- 1980-1989

- 1970-1979

- 1960-1969

- 1950-1959

- 1940-1949

- 1930-1939

- 1920-1929

- 1910-1919

- 1900-1909

- high-rise

- incremental

- low-rise

- low income housing

- mid-rise

- new town

- participatory design

- sites & services

- slum rehab

- Marion Achach

- Tanushree Aggarwal

- Rafaela Ahsan

- Jasper Ambagts

- Trupti Amritwar Vaitla (MESN)

- Purbi Architects

- Deepanshu Arneja

- Tom Avermaete

- W,F,R. Ballard

- Ron Barten

- Michele Bassi

- A. Bertoud

- Romy Bijl

- Lotte Bijwaard

- Bombay Improvement Trust

- Fabio Buondonno

- Ludovica Cassina

- Daniele Ceragno

- Jia Fang Chang

- Henry S. Churchill

- Bari Cobbina

- Gioele Colombo

- Rocio Conesa Sánchez

- Charles Correa

- Freya Crijns

- Ype Cuperus

- Javier de Alvear Criado

- Coco de Bok

- Jose de la Torre

- Junta Nacional de la Vivienda

- Margot de Man

- Jeffrey Deng

- Kim de Raedt

- H.A. Derbishire

- Pepij Determann

- Anand Dhokay

- Kamran Diba

- Jean Dimitrijevic

- Olivia Dolan

- Youri Doorn

- Constantinus A. Doxiadis

- Jane Drew

- Jin-Ah Duijghuizen

- Michel Écochard

- Marja Elsinga

- Carmen Espegel

- Hassan Fathy

- Federica Fogazzi

- Arianna Fornasiero

- Manon Fougerouse

- Frederick G. Frost

- Maxwell Fry

- Lida Chrysi Ganotaki

- Yasmine Garti

- Mascha Gerrits

- Mattia Graaf

- Greater London Council (GLC)

- Anna Grenestedt

- Vanessa Grossman

- Marcus Grosveld

- Gruzen & Partners

- Helen Elizabeth Gyger

- Shirin Hadi

- Marietta Haffner

- Anna Halleran

- Francisca Hamilton

- Klaske Havik

- Katrina Hemingway

- Dirk van den Heuvel

- Jeff Hill

- Bas Hoevenaars

- S. Holst

- Maartje Holtslag

- Housing Development Project Office

- Genora Jankee

- Henk Jonkers

- Michel Kalt

- Anthéa Karakoullis

- Hyosik Kim

- Stanisław Klajs

- Stephany Knize

- Bartosz Kobylakiewicz

- Tessa Koenig Gimeno

- Mara Kopp

- Beatrijs Kostelijk

- Annenies Kraaij

- Aga Kus

- Sue Vern Lai

- Yiyi Lai

- Isabel Lee

- Monica Lelieveld

- Jaime Lerner

- Levitt & Sons

- Lieke Lohmeijer

- Femke Lokhorst

- Fleur A. Luca

- Qiaoyun Lu

- Danai Makri

- Isabella Månsson

- Mira Meegens

- Rahul Mehrotra

- Andrea Migotto

- Harald Mooij

- Julie Moraca

- Nelson Mota

- Dennis Musalim

- Timothy Nelson Stins

- Gabriel Ogbonna

- Federico Ortiz Velásquez

- Mees Paanakker

- Sameep Padora

- Santiago Palacio Villa

- Antonio Paoletti

- Caspar Pasveer

- Casper Pasveer

- V. Phatak

- Andreea Pirvan

- PK Das & Associates

- Daniel Pouradier-Duteil

- Michelle Provoost

- Pierijn van der Putt

- Wido Quist

- Frank Reitsma

- Raj Rewal

- Robert Rigg

- Robin Ringel

- Charlotte Robinson

- Roberto Rocco

- Laura Sacchetti

- Francisco Javier Sáenz de Oiza

- Ramona Scheffer

- Frank Schnater

- Sanette Schreurs

- Tim Schuurman

- Dr. ir. Mohamad Ali Sedighi

- Sara Seifert

- Zhuo-ming Shia

- Geneviève Shymanski

- Manuel Sierra Nava

- Carlos Silvestre Baquero

- Mo Smit

- Christina Soediono

- Joelle Steendam

- Marina Tabassum

- Brook Teklehaimanot Haileselassie

- Kaspar ter Glane

- Anteneh Tesfaye Tola

- Carla Tietzsch

- Chiara Tobia

- Fabio Tossutti

- Paolo Turconi

- Burnett Turner

- Unknown

- Frederique van Andel

- Ties van Benten

- Hubert van der Meel

- Anne van der Meulen

- Anja van der Watt

- Marissa van der Weg

- Jan van de Voort

- Cassandre van Duinen

- Dick van Gameren

- Annemijn van Gurp

- Mark van Kats

- Bas van Lenteren

- Rens van Poppel

- Rens van Vliet

- Rohan Varma

- Stefan Verkuijlen

- Pierre Vignal

- Gavin Wallace

- W.E. Wallis

- Michel Weill

- Julian Wijnen

- Afua Wilcox

- Ella Wildenberg

- V. Wilkins

- Alexander Witkamp

- Krystian Woźniak

- Hatice Yilmaz

- Haobo Zhang

- Gonzalo Zylberman

- Honours Programme

- Master thesis

- MSc level

- student analysis

- student design

- book (chapter)

- conference paper

- dissertation

- exhibition

- interview

- journal article

- lecture

- built

Tema

Constantinos Doxiadis

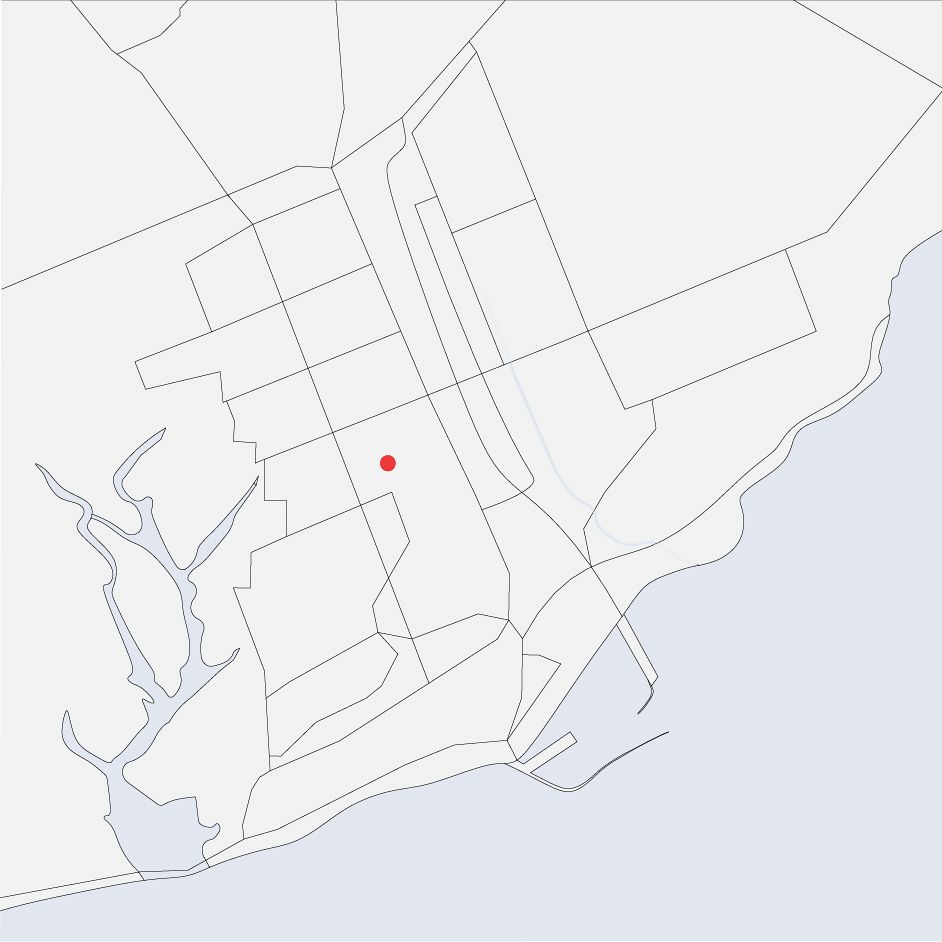

In 1957, Prime Minister Kwame Nkrumah declared Ghana independent. While Ghana was still a British colony, the decision was made to build Tema Harbour, as part of the Volta River Project 1. Along the way, it was decided that an entire new city in this area was needed. An English planning team began this process in the 1950s, but their carefully designed, winding road patterns didn’t provide the fast paced and rational image that Nkrumah was after. In 1960 he hired Greek planner Constantinos Doxiadis to speed and scale things up as well as rationalize the urban plan.

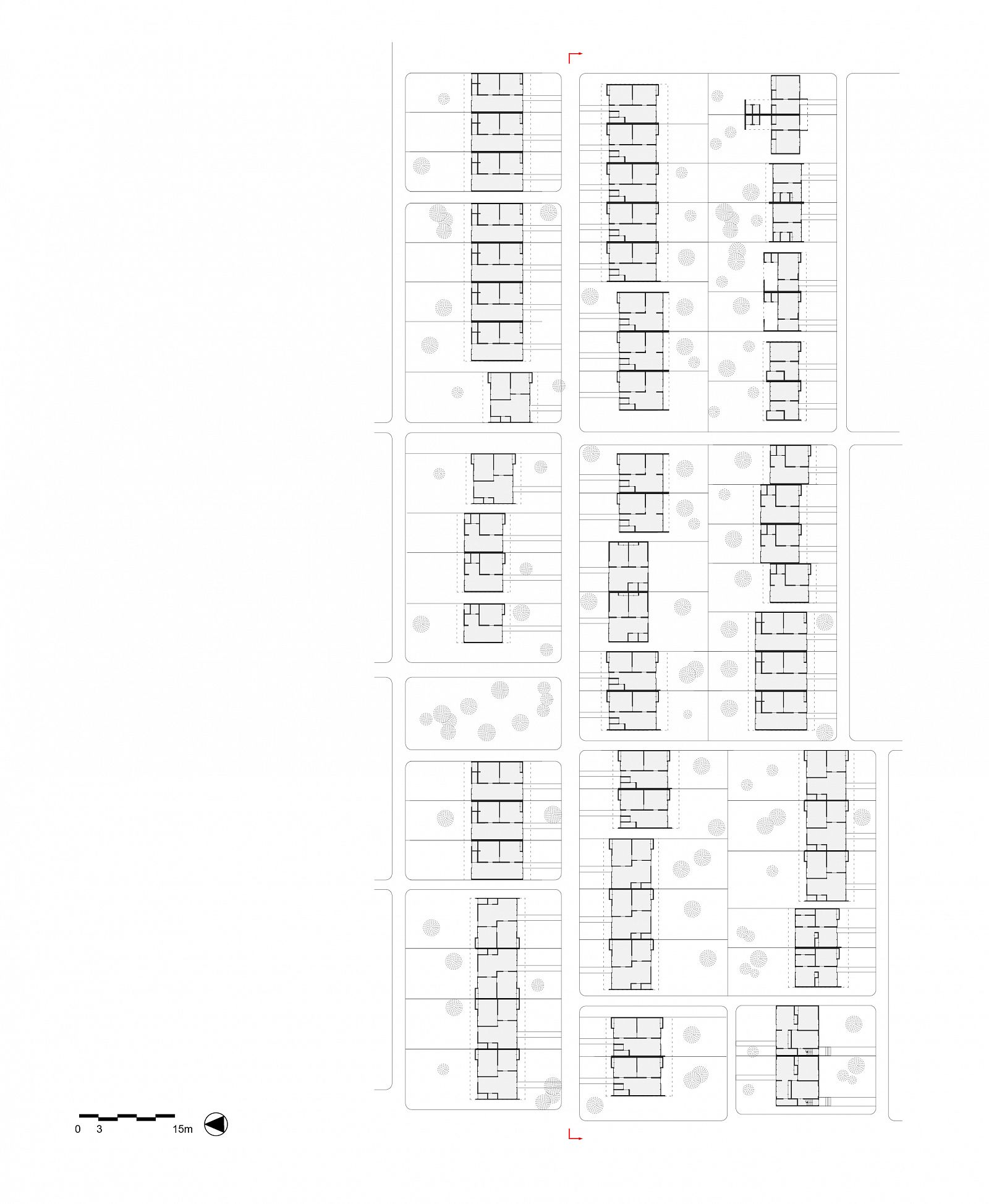

Doxiadis’s plan for Tema was based on a mathematical system that was rigidly hierarchical, with roads in eight different classes ranging from footpaths connecting houses (Road I) to highways (Road VIII), and residential areas ranging from a small cluster of houses (Community Class I) to the city as a whole (CC V) and even to the larger scale of the metropolitan region (CC VI). The familiar hierarchical order of the English New Towns was significantly enlarged in scale. Doxiadis systematized and took all whimsicalities and irregularities out of the existing urban plan. The first two (already built) Communities of Tema were incorporated in an orthogonal grid of main roads, which delineated a series of identical, numbered neighbourhoods (Communities Class IV), each with their own centre, including shops, high schools and government buildings. Every Community was divided into four smaller parts (CC III), again each with their own centre containing daily shops and primary schools. The direction of the urban grid was slightly diagonal, adjusted to profit from the prevailing direction of the wind.

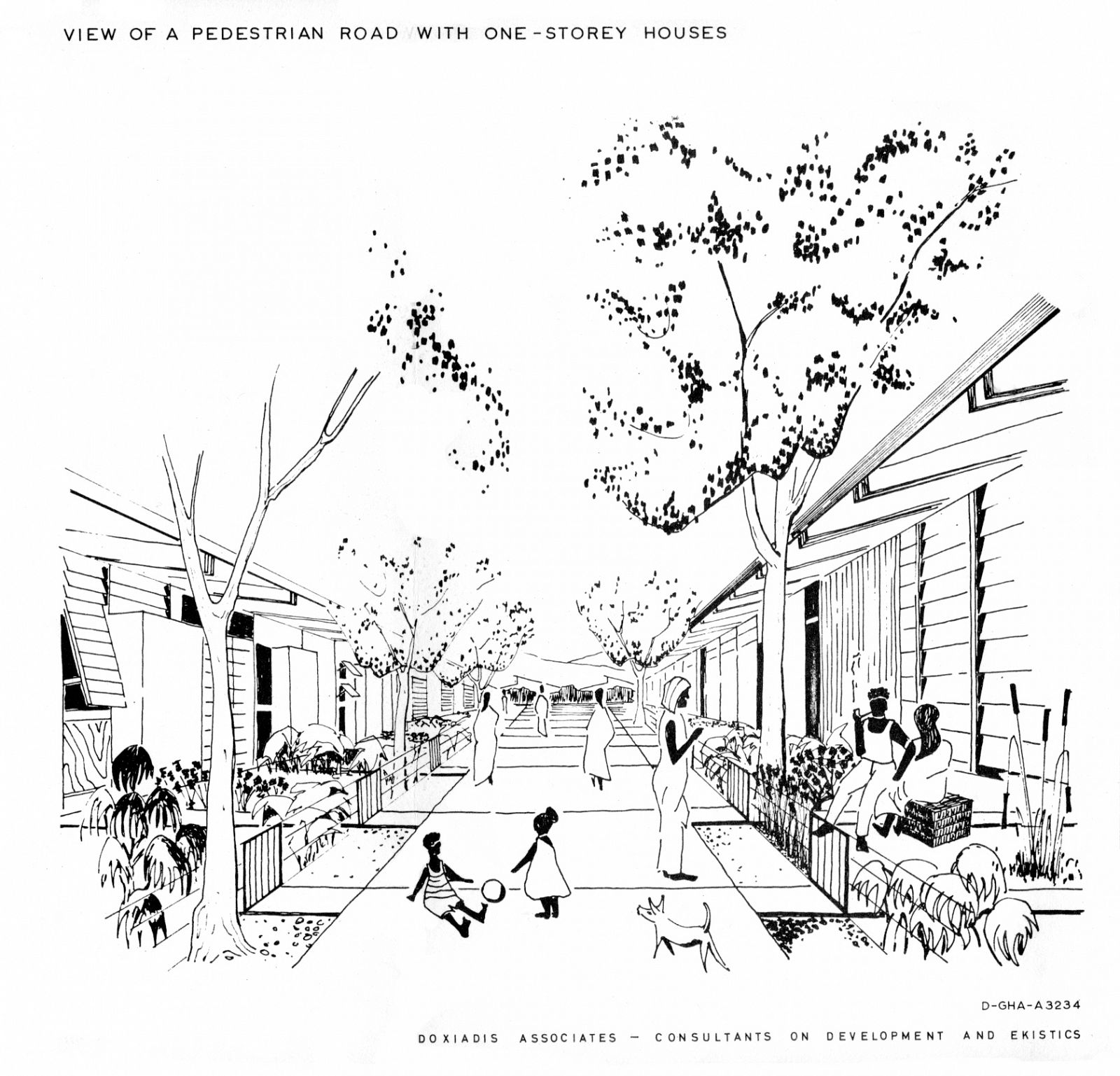

One of Doxiadis’s most important goals was to facilitate social cohesion within the Communities – a necessary goal in both a country that still had many differences and feuds between tribes and a city in which every inhabitant was a newcomer without existing social structures to fall back on. Therefore the design of public buildings and public space was a priority. All these were carefully standardized: the schools, the marketplaces and the government institutions, as well as the roads, paths and squares, along with the planting and trees along them.

While the city was indeed meant for a mix of incomes, these were hardly ever mixed within each community: low incomes were concentrated next to the industrial zone and along the highway, while the highest incomes were housed along the green areas and lagoons. Doxiadis also provided for the lowest incomes by including areas in which migrants could build their own houses (Community 9). It was an example of ‘sites & services’, the approach made popular in the 1970s by John Turner, the British architect who advocated self-organized building, although he also believed it was far from being an ideal solution that truly gave residents the ability to organize themselves and develop their preferred housing solutions.2

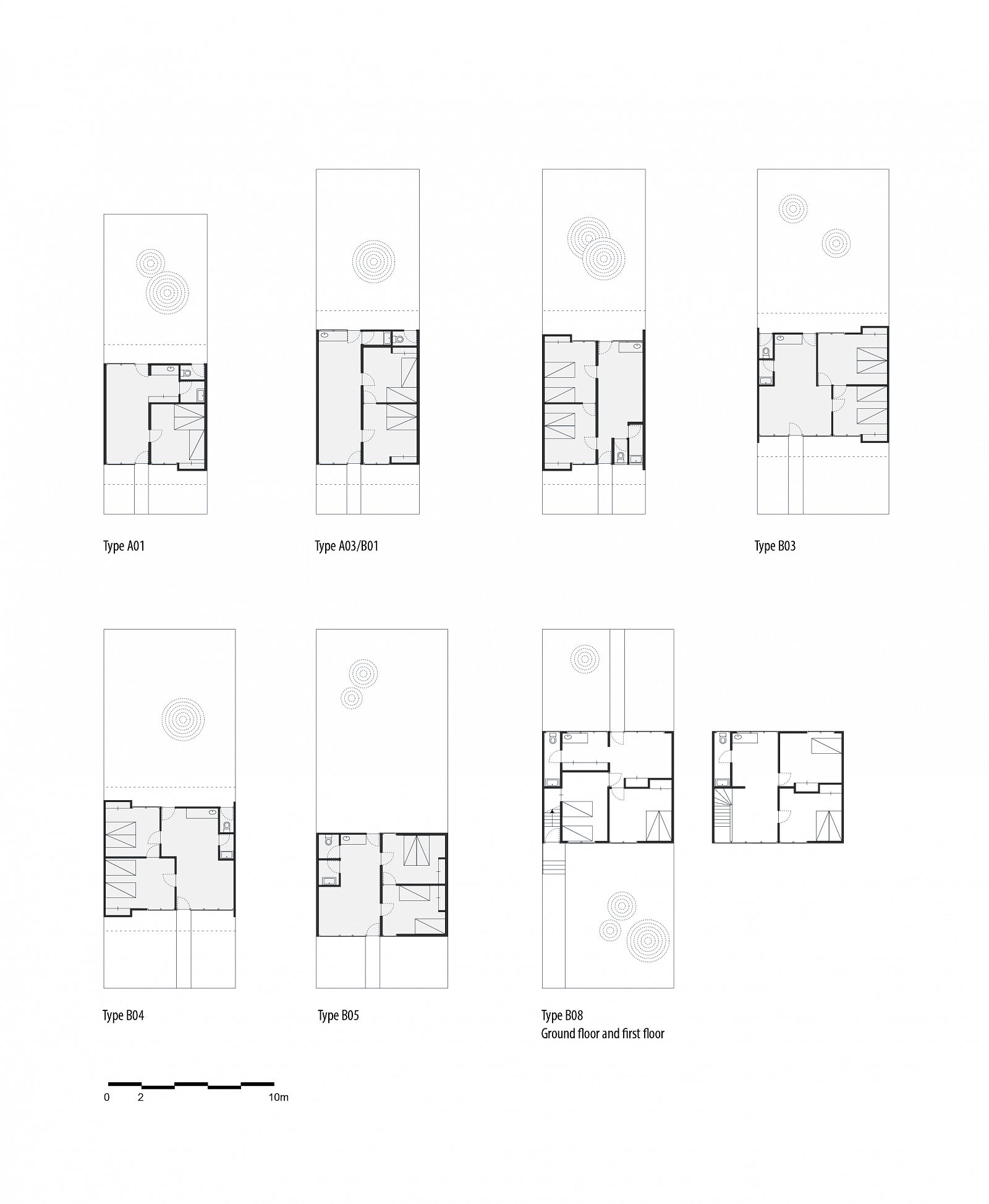

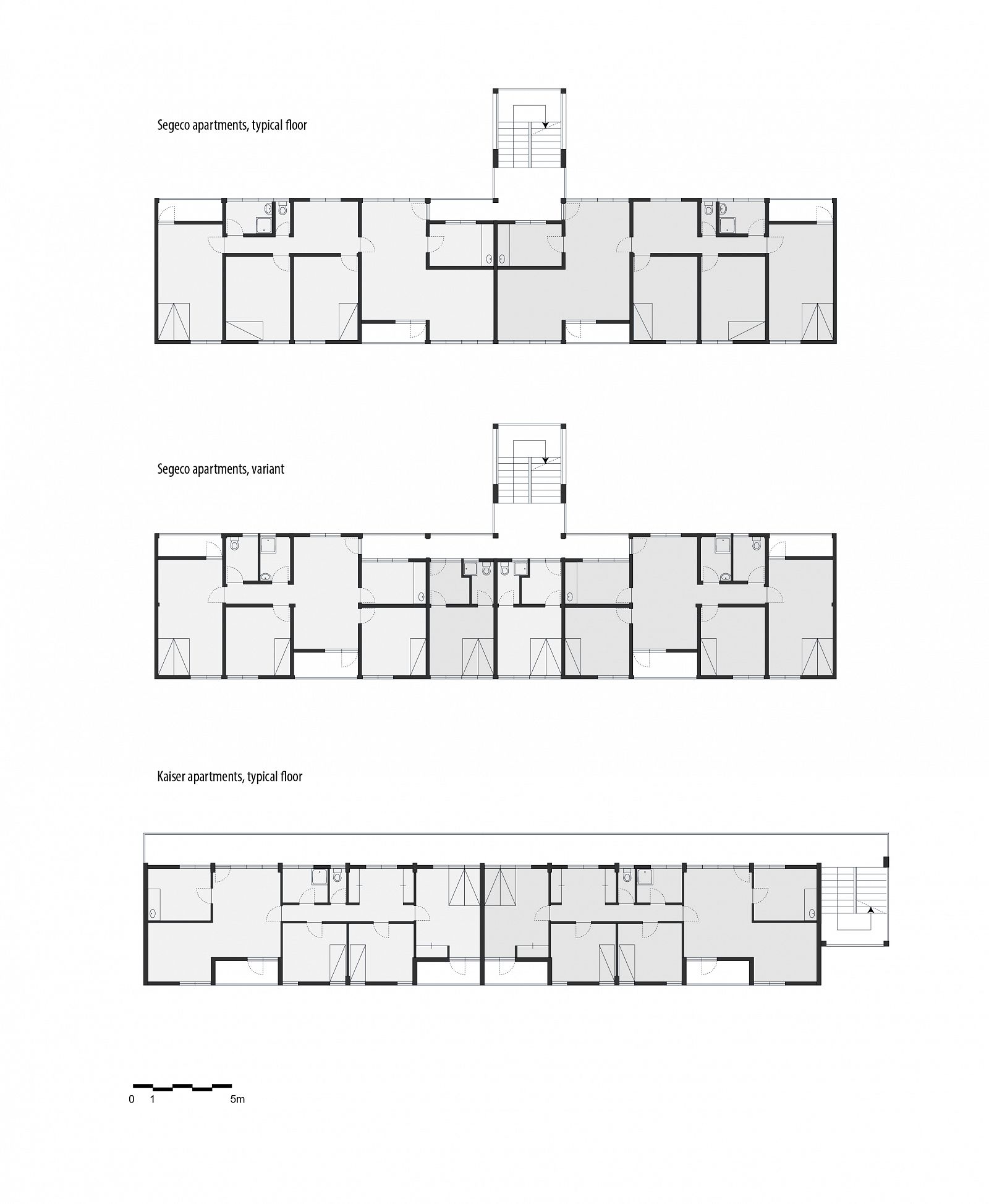

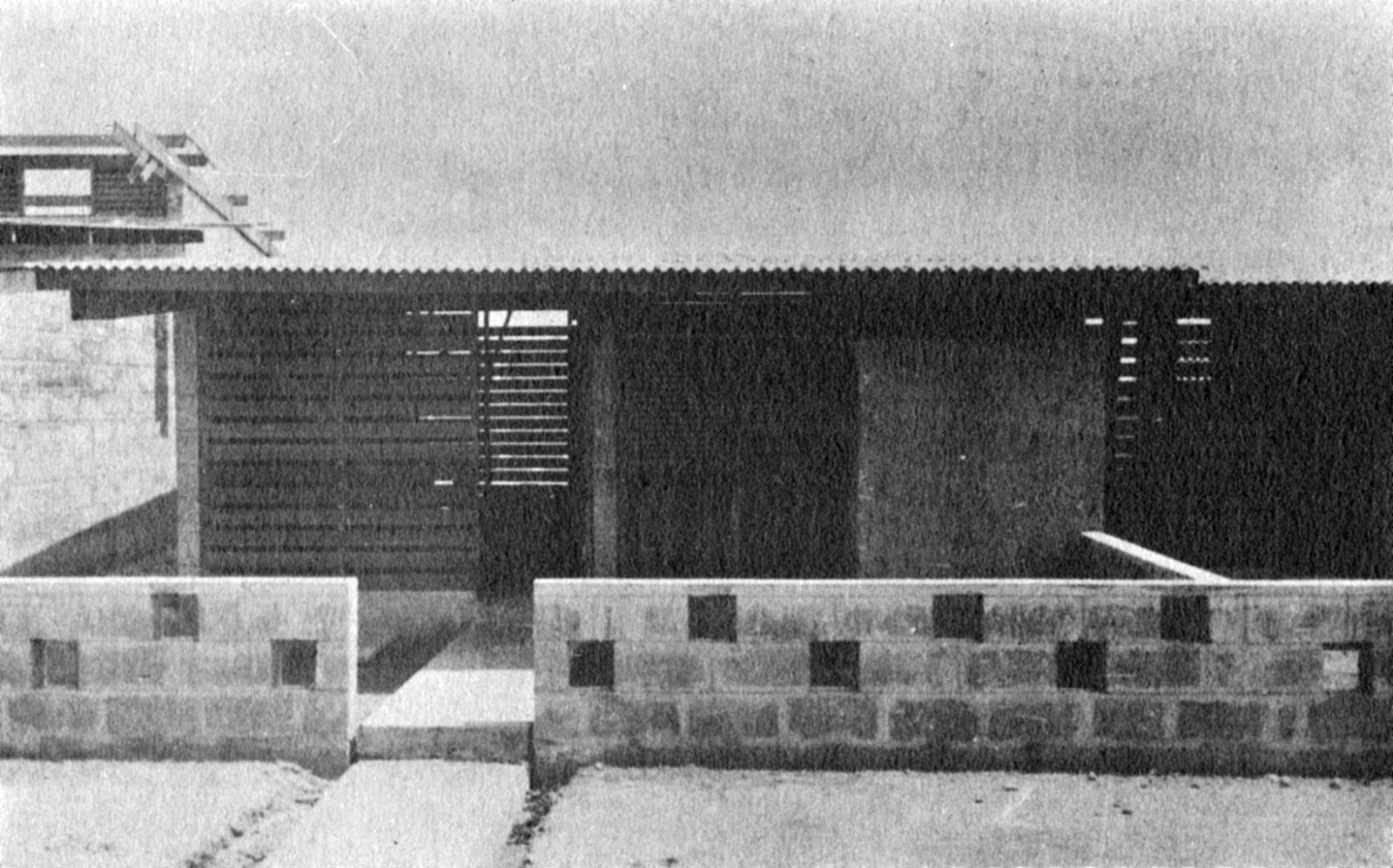

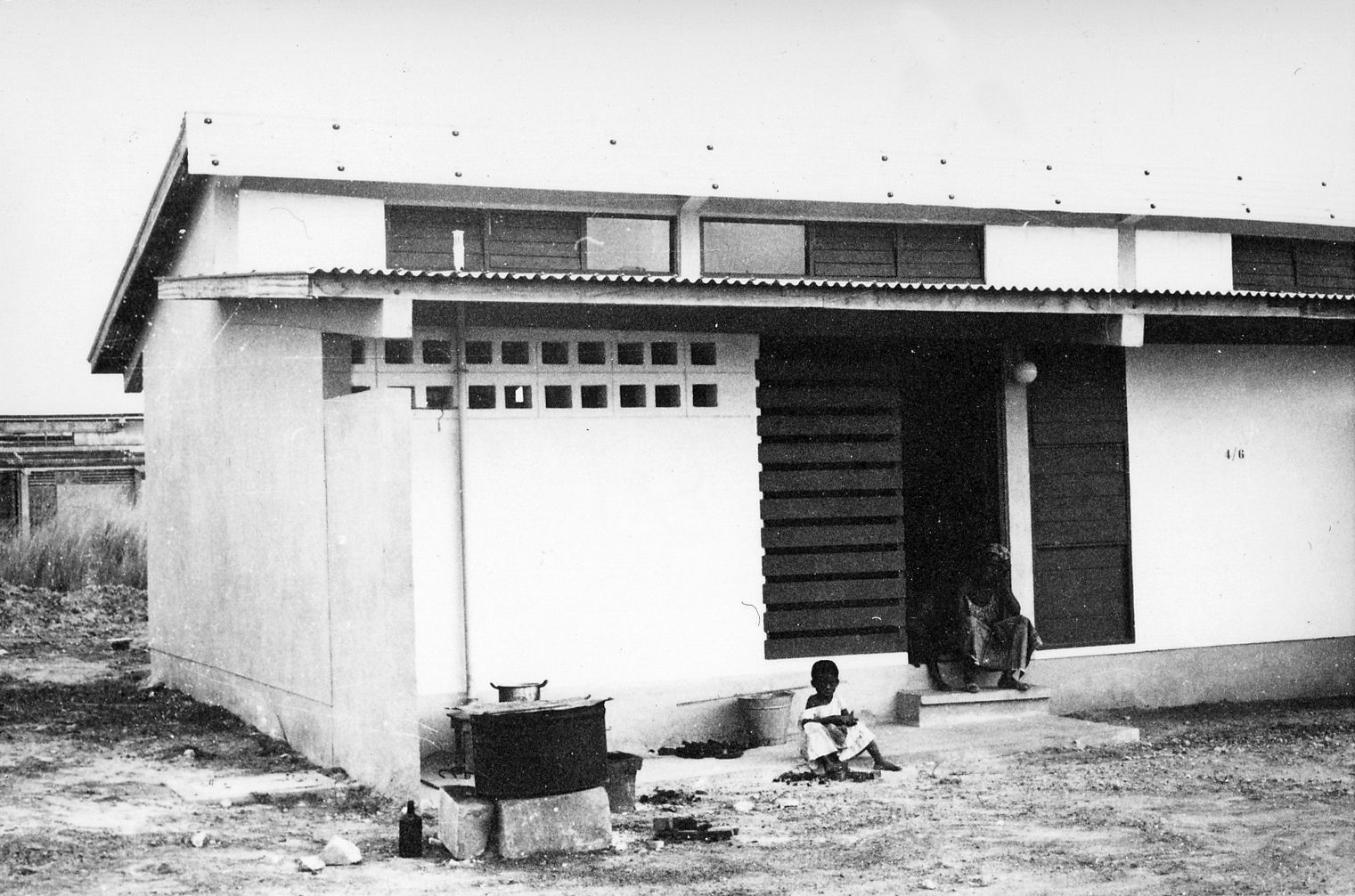

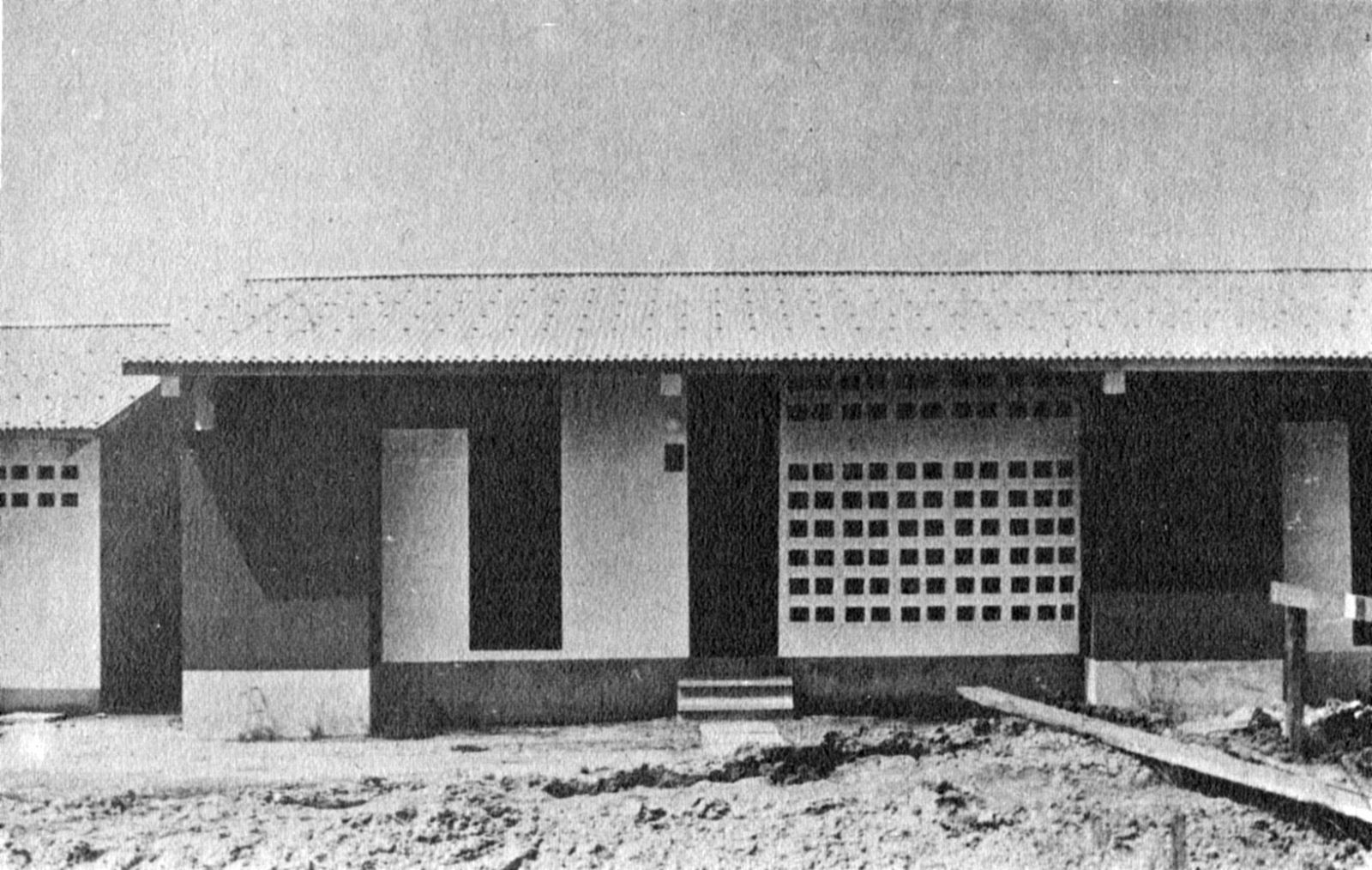

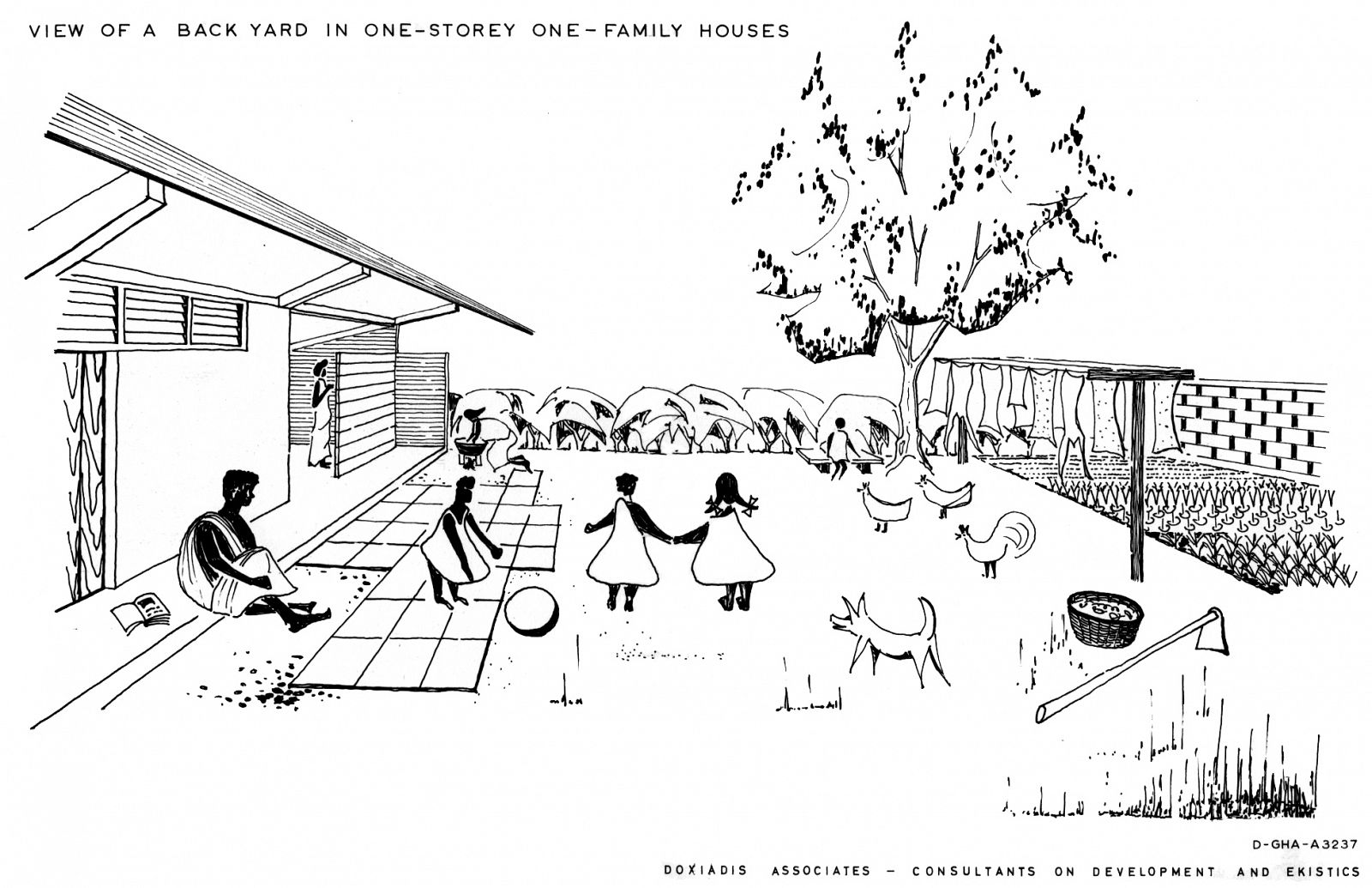

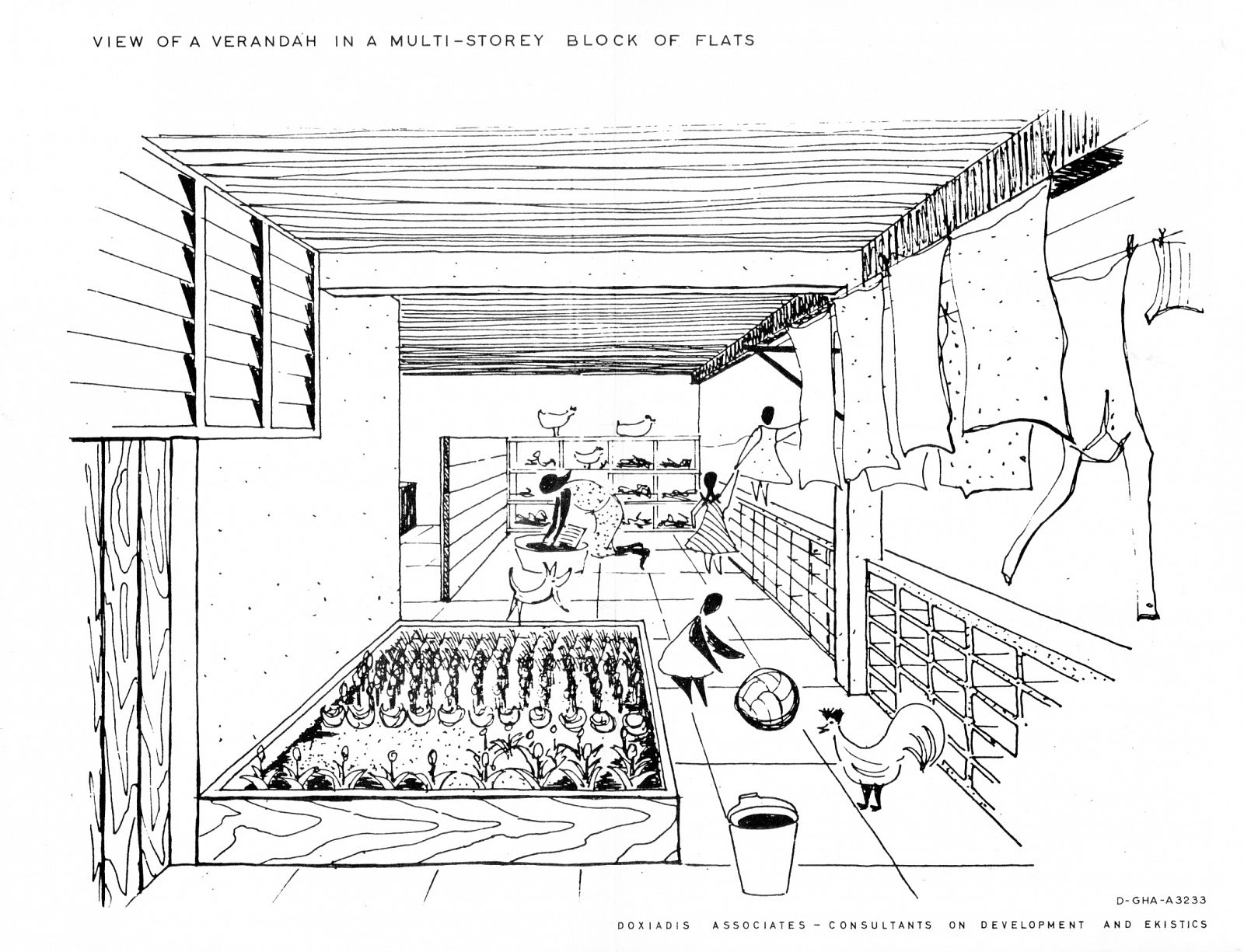

The development of the housing types shows how Doxiadis rejected the compound house. In the many series of experimental houses he developed for Community 4, there were bungalows, terraced houses, apartment buildings and every variation possible was tested, but they were all geared to the modern, nuclear family. Different from Maxwell Fry and Jane Drew, who accepted the local housing habits, he (like Prime Minister Nkrumah) decided that the extended family was unfit for a modern industrialized society.

The unlikely image of Doxiadis’s city was that of nicely designed, English style suburban terraced houses with gardens, lived in by immigrants from different tribes, working in industry. It was an anxious, dynamic industrial metropolis designed as a suburban pastoral. But Doxiadis’s sketches also show he was not romanticizing: it would also be noisy, lively and even sordid. And that is exactly what happened.

Today, the city of Tema doesn’t look like a clean English Garden City anymore. The modernist terraced houses are hidden behind self-built rooms and shops and the wide streets are lined with illegal kiosks. Though not intended this way, the New Town still takes advantage of the unusual amount of open space that was originally designed. The institutions that were planned – schools, hospitals, churches and community centres – also function well and are widely and actively used. Tema is regarded in Ghana as a desirable place to live. The city seems to have turned into a haven for the middle class, with plans to redevelop the first public housing areas by substituting them with commercial housing.

-

1The Volta River Project included the building of an aluminum smelter in Tema, the building of a huge dam in the Volta River(now: Akosombodam) and a network of power lines installed through southern Ghana.

-

2John F.C. Turner, ‘Housing as a verb’, in: John F. C. Turner, Robert Fichter (eds.), Freedom to build (New York: Macmillan,1972), 148-175.

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Drawing: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Drawing: © TU Delft, Delft Architectural Studies on Housing (DASH)

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Drawing: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Photo: © Michelle Provoost

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Drawing: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Photo: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

Drawing: © Constaninos and Emma Doxiadis Foundation | Source: Constantinos A. Doxiadis Archives

-

1The Volta River Project included the building of an aluminum smelter in Tema, the building of a huge dam in the Volta River(now: Akosombodam) and a network of power lines installed through southern Ghana.

-

2John F.C. Turner, ‘Housing as a verb’, in: John F. C. Turner, Robert Fichter (eds.), Freedom to build (New York: Macmillan,1972), 148-175.